When ‘Mea Culpa’ Is the Best Marketing | Intelligence, BoF Professional

LONDON, United Kingdom — Ganni wants you to know it’s not good enough.

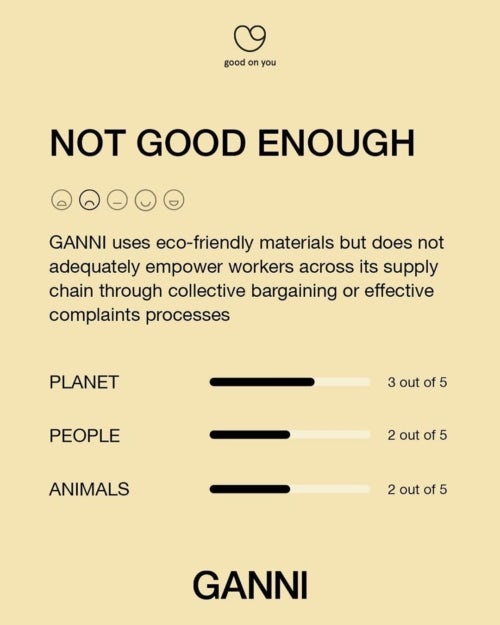

Earlier this month, the cult Danish label, known for its flattering wrap dresses and viral trend pieces, posted its latest score from sustainable brand rating platform Good On You on one of its Instagram accounts; the company scored a sad face.

It’s an unusually self-deprecating move in an industry historically obsessed with creating a carefully-curated, aspirational image. But in a rapidly-shifting world, where consumers want brands to show progress on challenging and complicated issues like climate and social justice, marketing is changing too.

Though many companies still tout sustainable collections and focus on promises of long-term improvements, a growing number are providing an open account of where they still have work to do.

“Marketing has always been about being perfect… [but] we started to see people going into this very radical shift of saying ‘we’re not perfect,’” said Carrie Ellen Phillips, a partner at communications and brand consultancy firm BPCM. “I think people who buy things respond to brands who are as imperfect as they are, and want as badly as they do to make the world a better place.”

Ganni accompanied its Instagram post with an explanation of why it scored poorly and what it’s doing to improve its performance.

“We’re not perfect and our journey towards doing better isn’t either,” the company said in its post, laying out plans to be more specific about sustainability targets and formalise policies on animal welfare, while also pointing to limitations in the rating system.

Ganni shared a poor score from sustainability ratings platform Good On You on one of its Instagram accounts.

The company also picked its channel carefully, posting the score to its Ganni.Lab Instagram account, which is focused on the brands’ sustainability initiatives. It has a much smaller following than the main account, which targets an audience with a wider range of interests.

The strategy reflects a broader debate playing out across the industry, as brands grapple with how to effectively communicate environmental and social initiatives to an ever-more engaged and critical consumer base.

It’s an increasingly pressing subject because, since the pandemic, sustainability has been one of the few topics that continues to resonate for brands. Social engagement around the topic saw an uptick year-on-year across most channels between September and October, according to data analytics firm Launchmetrics. In a recent survey of European consumers by McKinsey, more than 60 percent of respondents said they considered the way brands promote sustainability as a factor in purchasing decisions. And searches for sustainable products on fashion platform Lyst increased 76 percent in the six months from October last year to April.

“What we’re seeing in the research, you can see that in the online search behaviour of consumers,” said Karl-Hendrik Magnus, a senior partner at McKinsey. This “is a massive wake up call to brands… to very much rethink how they communicate their credentials to the consumer.”

Fashion is responding. Over the summer, a flurry of new platforms launched, promising to only feature sustainable products. Selfridges’ new flagship campaign is entirely focused on the company’s five-year strategy to shift to more sustainable practices. Last week, Gucci launched on resale site The RealReal with the promise to plant a tree for every item purchased. Even Amazon has started labelling products that meet more climate-friendly standards.

The initiatives are also, by and large, becoming more sophisticated, providing more information and transparency around what qualifies a product as sustainable. Companies that only “pay lip-service and use minimal environmental efforts as pure marketing… are vastly underestimating their customers,” said BPCM’s Phillips. The initiatives that resonate best with consumers are ones that acknowledge imperfection, she said.

That requires the industry to get comfortable with a growing level of transparency.

For instance, earlier this year, Allbirds started publishing a carbon “calorie count,” disclosing the carbon footprint associated with its major products and committing to continue to lower that level. The initiative features prominently on the company’s website, alongside an acknowledgement of the work that’s left to do: “Our goal — have no carbon footprint from the start. The first step to reduce our footprint is to measure it. And even though we’re not at zero yet, we can be. It’s all part of the plan.”

Last month Swedish brand Asket launched an “Impact Receipt” that breaks down the emissions, water use and energy consumption associated with four of its top-selling products. The company worked with the Research Institute of Sweden to collate the data and intends to roll the initiative out across its entire collection by mid-2021.

“We just felt that we just needed to come clean,” co-founder August Bard Bringéus said. “We see the industry grappling to meet an increasingly conscious customer, but mostly that turns into greenwashing.”

The strategy’s already paying dividends in terms of engagement, with consumers spending more time reading about products’ impact than they normally do on the site.

Additional reporting by Sarah Kent.

Related Articles:

How to Avoid the Greenwashing Trap

These Designers Want to Fight Climate Change. Just Don’t Call Them ‘Sustainable’

Can Fashion’s New Activists Make Sustainability Sexy?