Risk, Resilience and Rebalancing in the Apparel Supply Chain | Opinion

This article appeared first in The State of Fashion 2021, an in-depth report on the global fashion industry, co-published by BoF and McKinsey & Company. To learn more and download a copy of the report, click here.

Much has been written about how to make supply chains more resilient. But many companies, wary of eroding efficiency, have spent recent years putting off the preventive measures that could minimise the impact of future disruptions.

Today, the pandemic has once again driven home the urgency of managing operational and supply-chain risk. While every goods-producing sector is confronting this challenge, the apparel industry stands out as one of the most heavily exposed. Factories are not only coping with workplace health and safety issues. They also face financial distress from orders drying up as falling consumer demand hits fashion brands and retailers worldwide.

The current crisis underscores the fact that the unexpected now has to be considered probable. To cope with eventualities, companies need to embed at least a baseline level of losses from disruption into their financial planning. This information can help global apparel brands and retailers make better decisions about how to invest in supply-chain stability and prepare themselves to better withstand future disruptions.

Disruptions Are Growing More Frequent and Severe

It’s not just a figment of our collective anxiety: the world really has become riskier. Changes in the environment and in the global economy are increasing the frequency and magnitude of supply-chain shocks. Dozens of weather disasters each year cause damages exceeding a billion dollars each — and the economic toll caused by the most extreme events has been escalating. A world of shifting geopolitics is producing more trade disputes, tariffs and uncertainty. Interconnected supply chains and global flows of data, finance and people offer more “surface area” for risk to penetrate. Ripple effects can travel rapidly across these network structures — and across national borders.

McKinsey surveyed dozens of supply chain experts in mid-2020 to gauge just how frequently things go wrong. Their responses were surprising: Manufacturers can expect disruptions lasting one to two months to occur every 3.7 years on average, and those dragging on for two months or longer happen roughly every five years. Lean global supply chains deliver real margin improvements, but frequent disruptions have to be fully accounted for as a real cost of doing business with this kind of structure.

Companies are attuned to some types of risk simply because they encounter them more often. Data breaches, theft and industrial accidents happen. Trade disputes dominate the headlines. Most multinationals have systems and functions in place to try to prevent these types of incidents or to respond to them quickly.

But some types of shocks are not on the typical company’s radar. They may be rare occurrences, but they can inflict much bigger losses. These include extreme weather, earthquakes, financial crises, major terrorist attacks and, yes, pandemics. If 2020 has taught us anything, it’s the folly of assuming that extreme scenarios will never come to pass.

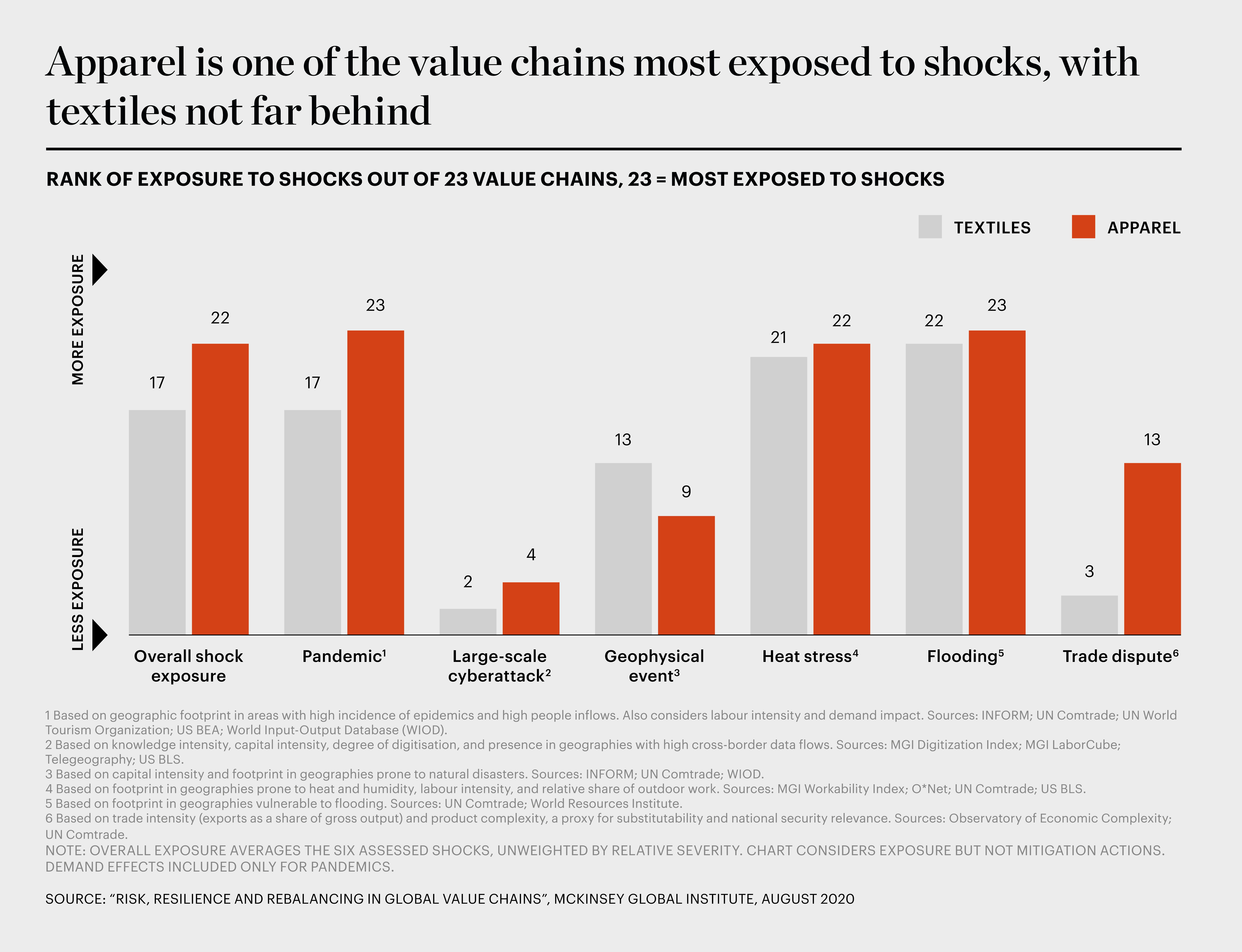

We analysed a wide range of industries to assess their exposure to specific types of shocks. Out of the 23 value chains analysed, apparel emerged with the second-highest level of exposure (topped only by communication equipment; see Exhibit 11). The labour-intensive nature of the apparel value chain, as well as its geographic footprint, makes it particularly exposed. In the current pandemic (as well as any that might occur in the future), apparel manufacturing is susceptible to shutdowns because of this and unpredictable drops in consumer demand. Furthermore, a large share of apparel exports come from Bangladesh and Vietnam, which are subject to heat stress and flooding. The industry as a whole is also exposed to workplace risks — a painful reality brought home by the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh, which killed more than 1,100 garment factory workers and injured thousands more. This tragic disaster spurred the industry toward more active supply chain management and transparency about working conditions. But more can be done.

Over the Course of a Decade, Companies Can Expect Disruptions to Erase Half a Year’s Worth of Profits at a Minimum

Supply-chain shocks can have significant financial consequences. We built representative income statements and balance sheets for hypothetical companies in 13 different industries, using actual data from the 25 largest public companies in each. We then put them through a stress-test to see what kind of financial losses a 100-day shutdown would produce.

Our scenarios show that, over the course of a decade, companies in most industries can expect a single production shock lasting 100 days to wipe out between 30 and 50 percent of one year’s EBITDA. For the average textiles and apparel company, that number is about 40 percent. An event that also disrupts distribution channels would push the losses sharply higher in some industries. The magnitude of financial loss depends on whether a company holds enough inventory to get it through the period of interrupted production, as well as whether it has the ability to ramp costs up and down. Most inventory of finished goods in the apparel industry is held by retailers, which means that production shutdowns could significantly impact manufacturers’ profits.

These are the hidden and recurring costs of doing business with complex supply chains in a riskier world — and they are only the baseline. Estimating these costs allows companies to better understand how much they can expect to invest in resilience and still see a long-term pay-off.

Will Value Chains Shift Across Countries?

Today, much of the discussion about resilience involves questioning where things are made, considering lower-risk locations and reducing the geographic breadth of supply chains to make them easier to manage. But the interconnected nature of value chains limits the economic case for making large-scale changes in their physical location. We estimated what share of global exports could move to different countries based on the business case and how much might move due to policy interventions. To consider whether economic factors would support a geography shift, we looked at whether movement is already underway, how knowledge- and capital-intensive the value chain is, how tied it is to geology and natural resources, and the degree to which it is already regionalised. We also considered non-economic factors, such as importance to natural security, competitiveness and self-sufficiency.

Lean global supply chains deliver real margin improvements, but frequent disruptions have to be fully accounted for as a real cost of doing business with this kind of structure.

Apparel stands out as one of the industries with the largest share of total exports that could potentially move to different countries (36 to 57 percent in apparel, as well as 23 to 45 percent in textiles). Supply chains are already evolving in these highly traded, labour-intensive industries. China has long been the world’s dominant maker, and it still accounts for some 29 percent of apparel sold globally. But the country’s wages are rising, and Chinese producers can now focus on meeting domestic demand. In 2005, China exported 71 percent of the finished apparel goods it produced. By 2018, that share was just 29 percent. While some apparel production may nearshore to US and EU markets, most would likely shift to Southeast Asian countries due to their comparative advantage in labour and overhead costs. As China’s exports have plateaued, more apparel manufacturing for export has moved to places such as Bangladesh and Vietnam. Turkey has become a major producer of clothing that is exported to Europe. Newer hubs such as Cambodia, Ethiopia and Honduras are also beginning to emerge. But companies that begin sourcing from these and other developing economies will need to understand and safeguard against a wide range of risk, from natural disasters to future pandemics.

Will a New-Found Appreciation For Risk Prod Companies to Act?

The need to make supply chains more transparent and resilient has been widely discussed for years. But most strategies for doing so require making long-term investments or accepting a slightly higher cost of goods. For that reason, only a small group of leading companies have taken decisive action.

However, this time really might be different. Companies are considering a range of resilience measures — and most of them do not involve finding new suppliers in different locations. They can opt to hold more inventory, build redundancies into transportation and logistics, reconfigure factories and warehouses to withstand natural disasters and develop the ability to flex production across multiple sites. For example, Esquel, a supplier to brands such as Hugo Boss and Nike, found itself unable to export fabric from Mainland China to its factories in Vietnam during the initial Covid-19 outbreak. But the company activated its back-up plan and pivoted to shipping through Hong Kong to keep production going.

As China’s exports have plateaued, more apparel manufacturing for export has moved to places such as Bangladesh and Vietnam.

Companies not only have a renewed sense of urgency about addressing risk; they also have a new way forward. The pandemic has occurred at a moment when manufacturing technologies are leapfrogging forward. Particularly when compared to other manufacturing industries, apparel production has a great deal of room to digitise and reap the benefits.

In our experience, creating supply chain transparency through digitisation can boost both productivity and resilience. It is critical to gain visibility into who supplies your suppliers and spot any vulnerabilities hidden deep in the lower tiers of the network. When the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, Nike’s digitised supply chain enabled the company to quickly shift products headed for brick-and-mortar stores to e-commerce fulfilment centres in China. As a result, it minimised the hit to revenue.

Some companies have made it a point to model prioritised risks, but they have often done so by looking at these shocks as discrete rather than cascading events. Now, analytics tools enable a more sophisticated approach that quantifies broader and more integrated scenarios. This makes it possible to look not only at extreme one-off events but also at their knock-on effects and the ongoing business cycle, taking correlations into account. Scenarios can also incorporate a range of risk-mitigation strategies to test which would be most effective. The results can then inform strategic planning and capital allocation decisions.

Preparing for future hypotheticals has a present-day cost. But if those investments focus on digitally connecting the entire value chain from end to end, they can pay off over time — not only minimising future losses but boosting productivity and strengthening entire industry ecosystems today.

This article draws on a larger body of research on trade and global flows from the McKinsey Global Institute, the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company. The latest report in this series is Risk, Resilience and Rebalancing in Global Value Chains. The authors would like to thank Kyle Hutzler and Dhiraj Kumar for their contribution to this article.