Iñaki Williams: ‘My parents crossed the desert barefoot to get to Spain’ | Athletic Bilbao

“We were at home one day in Bilbao watching the television when something came on – I can’t remember exactly what – and I asked her again. My mum turned it off and said: ‘OK. The moment’s come for me to tell you. Sit down, I think you’re ready to hear the story of papa and me now. When she told me I was left cold. Hearing that leaves a deep impression. Wow. It’s like something in a film and my parents lived it.”

Iñaki Williams stops and takes a breath. He was 20 that day, already playing for Athletic Club. Pushed into the public eye, he had been asked his story but couldn’t tell it properly because he didn’t know. Parts had been written wrong, but he didn’t really know that either. He too had asked, desperate to find out exactly where he was from. “It ate away at me,” he says. Until, at last, Maria told him.

She told him how they had left Ghana and crossed the Sahara without food or water, about those who didn’t make it and how that could have been them. How they hid things the only place they could. How, pregnant with him, she climbed the fence into Melilla, Spain’s north African enclave. And how she and Felix were arrested, a lawyer whose name he still doesn’t know and, to his regret, never will providing a lifeline, a way of reaching the city where he was born. His place, where he has made history.

Last Friday night, 28 years on, Iñaki Williams played his 203rd consecutive league game, a record and the culmination of a journey that began before he was born. “Hearing my parents’ story makes you want to fight even harder to give back everything they sacrificed for us. I couldn’t ever repay them – they risked their lives – but the life I try to give them is the one they dreamed of giving us. And, in some way, we can say: ‘We’ve done it.’

“You’d watch the news and see boats arriving from Africa, people climbing the fence [into Melilla] and I realised I didn’t really know how we got to Spain. It’s something I always asked but my mum avoided it because I was just a kid. And maybe she then thought if she’d told me when I started at Athletic at 18 it would have been a weight on my back. I knew my life was different to my friends’ and I could imagine, but when you hear the details …

“Details like: I didn’t know they had crossed the desert by foot. I knew my dad had problems with the soles of his feet but not that it was because he had walked barefooted across the Sahara sand at 40, 50 degrees.

“They did part in a truck, one of those with the open back, 40 people packed in, then walked days,” Williams continues. “People fell, left along the way, people they buried. It’s dangerous: there are thieves waiting, rapes, suffering. Some are tricked into it. Traffickers get paid and then halfway say: ‘The journey ends here.’ Chuck you out, leave you with nothing: no water, no food. Kids, old people, women. People go not knowing what’s ahead, if they’ll make it. My mum said: ‘If I knew, I would have stayed.’ She was pregnant with me but didn’t know.

“They reached Melilla, climbed the fence and the civil guard detained them. They didn’t have papers and came as migrants, so you get sent back. When they were in jail a lawyer from [the Catholic aid organisation] Caritas who spoke English said: ‘The only thing you can try is tell them you’re from a country at war.’ They tore up their Ghanaian papers and said they were from Liberia to apply for political asylum. Thanks to him, we arrived in Bilbao.”

Williams smiles. Bilbao, of all places. “Destiny,” he calls it. Born there, the doors opened to Athletic with their Basque-only policy. His club. “My friends and I talk about it: bloody hell, incredible. Everything happens for a reason. If I hadn’t been born in Bilbao, I could never have played for Athletic. My parents crossed the desert and were taken to the Basque country. That doesn’t feel like chance.”

Maria and Felix moved to Pamplona, 150km south-east, getting state housing in “a humble, hardworking barrio with lots of races where people made ends meet however they could”. They met Iñaki Mardones – which is where Williams got his name – a priest who became his godfather and their guardian. Clothes came from the church. There wasn’t much, but Williams insists: “I had food, something to wear, and compared to a many, many, people, I was rich. My parents’ story told me that.”

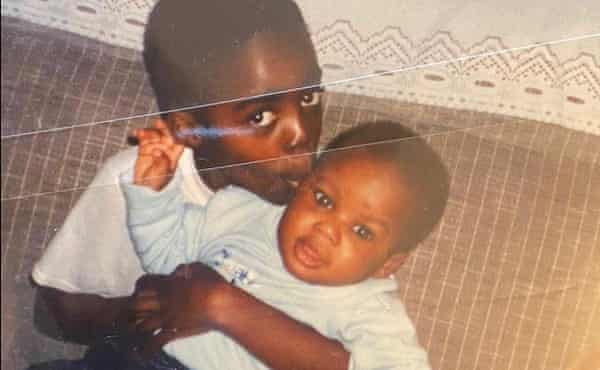

Williams’s dad worked as a shepherd, a cleaner on a building site, anything he could find which wasn’t always anything at all, later heading to London alone. “He worked in a shopping centre near Chelsea clearing tables in the food halls or as a security guard, tearing tickets at Stamford Bridge. Any job no one wanted.” Iñaki was 10 or 11. His brother Nico was two or three. Felix was gone a decade. Maria did two, three jobs at a time when there was work. Iñaki became almost a father to Nico.

And of course, he became a footballer, his first memory a kid called Xabi calling him down to the street to play at four or five. For a while, he even became a referee in local leagues: at €10 a game, it was valuable to him, although he needed more. He had promised his mum he would become a professional and at 18 joined Athletic, making his debut in December 2014 aged 20. “I knew making it would fix many things,” he says. “It wasn’t just the debut itself, it was what it brought. It meant bringing my dad back from London, reuniting my family after 10 years, my little brother having the paternal figure, stability, the family we wanted so badly. I dreamed of being a footballer but also reuniting my family.”

Williams was only the second black footballer to play for Athletic, after Jonas Ramalho. He is the only black player to have scored for the club but hopefully not for long: Nico, eight years younger, has joined him in the first team. The symbolic power is huge, a role he embraces. Subjected to racist abuse that convinced him and his teammates they would walk if it happens again, he has backed demonstrations and spoken with firm eloquence, beyond the game. Charismatic, direct, funny, his message reaches people. The pride is palpable at Athletic.

“People empathise with my story, identify with the sacrifice,” he says. “My arrival opened minds. Athletic have done me a lot of good and I hope I’ve done Athletic good. Footballers often don’t speak out, but it’s good for society. If you have the power to reach people you should. Racism is a stain, an illness to be eradicated. Not talking about discrimination allows it to exist, being permissive allows it to continue.

“Society is changing: it’s more open, there’s more immigration, more diversity. When I arrived, there were very few black kids; now there are more in the youth system. Diversity, movement, brings that and we’ll see it in the national team. England and France have many black players. Adama [Traoré] is here now, it’s changing. We’re going to get more used to seeing different faces in the same national team.”

Including his? the forward has played only once for Spain, a friendly against Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2016. It remains his target, approaches from Ghana turned down. “I’m grateful to where I grew and became who I am. Ghana tried to convince me, but I was born in Spain, in Bilbao. I won’t ever forget my family roots, but I feel Basque and can’t con anyone. I would be comfortable with Ghana, I’m sure, but I shouldn’t be there …”

There’s a grin. “And my mum knows how people live football there: it’s quite something, and she’d be worried about me,” he says, laughing.

“When my mum’s angry, she swears at us in Ghanaian but we speak Spanish. When my parents came, it was English but we lost that. I could have a conversation in English but it’s not fluent now. When my grandparents call, I speak to them in Twi. I admire and love Ghana, the culture, food, tradition. My parents are from Accra and I really enjoy going. But I wasn’t born or raised there, my culture’s here, and there are players for whom it would mean more. I don’t think it would be right to take the place of someone who really deserves to go and who feels Ghana 100%.”

The way that he feels Athletic, the club he supported and one that can feel almost like an unofficial national team sometimes. For whom he scored the winner in the Spanish Super Cup – only the second trophy they have won in 35 years. Williams always knew just one game for them would change everything; now there have been 304, 203 league matches in a row.

The last time he didn’t play was 17 April 2016, when his teammate Yuri Berchiche injured his left ankle – and, yes, he has made sure Yuri knows that. Since then, five and a half years passed without Ernesto Valverde, Cuco Ziganda, Toto Berizzo, Gaizka Garitano or Marcelino García Toral leaving him out, without suspension or injury. Despite Williams being Spain’s fastest player, the explosivity usually coming at the cost of torn muscles.

“The doctors and physios say it’s incredible, that it’s impossible for there to be a case like this again, especially playing high-intensity games every three days,” he says. “Thank my parents for the genes: I don’t know what it is but there’s something inside me.

“I’d be lying if I said I hadn’t played with knocks or pain; I’ve played on medication with injections, moments the manager and the team needs you. And I had two seasons going into the final weeks with four yellows. ‘Buah, if there’s a fifth, that’s a ban.’ But I don’t protest much or kick anyone,” he admits, laughing.

“[But] it wasn’t really until the last week that it was on my mind, when there were three games in seven days to break the record: home, away, home. You’re so close, there’s a risk, you think: ‘Woah, something could happen, I could lose this.’ Until then, you don’t think of it. Destiny is written.”

History is too, especially here. Across the training pitch where Williams sits at Lezama, under the famous arch brought from the old San Mamés, are two busts: Piru Gainza and Telmo Zarra. At the stadium, there is another of Pichichi. There may be no club with the liturgy of Athletic, no club that celebrates its tradition, its community, its past, like them. Somehow breaking the record here seems even more significant, Williams part of something bigger.

“It’s the hostia, bloody unbelievable,” he says. “Me and my teammates dreamed of being part of Athletic. I’ve lived that dream. So many people would give anything to be where we are. Athletic is a union, a family. Together, we’re strong. To be where I am, represent what I do, is incredible. To be able to say to my mum and dad, ‘We did it’, because everything they did was for us, to represent this club, wear this shirt, and for people to feel proud that I’m part of Athletic’s history.”

Now so is Nico. “I have a history I started to write seven years ago; he has to write his own,” Williams says. “We’re living this together, I’m proud of him and he’s doing very well, progressing fast, but he still has a lot, a lot, to prove and a lot, a lot, of work ahead. Let him be, let him grow, let him earn whatever comes.”

Just so long as that’s not 204 games in a row. Iñaki Williams laughs. “Well, if someone has to take the record off me, let it be my brother.”