How Worried Should Brands Be About China’s Tech Crackdowns? | China Decoded, BoF Professional

Internet giants in the world’s top two economies aren’t having the best start to the year.

As Silicon Valley’s big tech players brace themselves for tougher scrutiny under the Biden administration, their Chinese counterparts have, in recent months, become targets of President Xi’s regulators in areas like anti-trust and livestreaming.

Last November, China’s National Radio and Television Administration announced a crackdown on the thriving livestreaming sector. New regulations demand that platforms report to authorities regularly and provide notice prior to major events and streams involving celebrities; that hosts and viewers follow strict registration rules; and that limits are imposed on tipping, with teenagers banned from doing so altogether. The latter move, in particular, could dent revenues for firms from Yizhibo and Taobao Live to Xiaohongshu and Tmall (platforms of choice for Louis Vuitton and Burberry respectively).

The same month, Beijing revealed draft regulations aimed at combatting anti-competitive practices — from sharing consumer data to underhand agreements to disadvantage smaller rivals — and Alibaba Group affiliate Ant Group’s record-breaking $37 billion IPO was blocked by regulators just days before dealing was set to begin. Weeks later, Alibaba and WeChat owner Tencent were retroactively fined by China’s antitrust watchdog over acquisitions completed years ago.

Alibaba headquarters. Reuters.

“China’s top ten companies by market cap are all internet; the billionaires list is all internet; the economy is highly digitised and it’s all been accelerated by Covid. So I think this was coming and you see this in the US too,” said Rui Ma, host and founder of the Tech Buzz China podcast and partner at Synaptic Ventures.

Soon after Alibaba and Tencent were fined, China’s cybersecurity watchdog sought comment on draft rules concerning the range of data that apps can collect from users (a proposed data protection law was announced in October and is under review). To cap the year off, an investigation into alleged “monopolistic practices” at Alibaba was launched on Christmas eve.

These rules and investigations — potentially the tip of the iceberg for a wider regulatory overhaul — not only implicate the ways fashion and beauty brands target and engage with customers in the lucrative and indispensable Chinese market, but they also signal a potential shift in power away from dominant platforms brands currently rely on for sales and exposure. Here’s what three tech and retail experts make of the situation and what global firms need to know to prepare for a changing e-commerce landscape.

Reminding big tech who’s in charge

When it comes to recent anti-trust activity, Beijing’s message is clear: tech giants need to be reined in.

“China used to be growth at all costs,” says Rui Ma. But in the last five years, she adds, the stance has changed to one favouring stability. Siloed regulatory bodies and gaps in the law allowed firms like Alibaba and Tencent to take advantage of loopholes, making a crackdown somewhat inevitable. “Beijing doesn’t want to have a single overwhelming market player; they also don’t want to have growth they can’t control.”

In e-commerce, that overwhelming market player is Alibaba, which Ma estimates now holds over 50 percent of China’s e-commerce market share ahead of rival JD.com; the firm is the second-biggest publicly traded retailer globally, ranking only behind Amazon, according to GlobalData. In addition to drawing over 200 luxury brands to Tmall’s Luxury Pavilion arm and launching outlet business Luxury Soho, last year’s mega-deal involving Alibaba, Richemont and Farfetch has further cemented the giant’s role as a China’s fashion gatekeeper.

Beijing doesn’t want to have a single overwhelming market player; they also don’t want to have growth they can’t control.

“Certainly, if [Beijing’s] anti-monopoly drive has teeth, they are the market leader and will have the most to lose,” adds Matthew Brennan, tech analyst and co-founder of digital marketing firm China Channel. Meanwhile, Beijing’s efforts to break up the country’s tech oligopoly will likely be good news for smaller platforms like Xiaohongshu and Douyin and increase competition throughout an already cutthroat tech sector. Alibaba did not respond to BoF’s request for comment.

But the devil will be in the details: the laws may end up filled with loopholes or unenforceable. “What the regulations say on paper is very reasonable-sounding … but they’ve definitely left enough leeway in there so that there’s a spectrum of execution,” says Ma.

For large firms, these moves serve as a warning. Ma notes that Alibaba and Tencent’s fines — amounting to around 500,000 yuan (around $77,276) each — are peanuts for two of the largest tech firms in the country. “It’s not meaningful from a P&L standpoint but it’s sending a very strong signal.”

But Arnold Ma, founder and chief executive of China-focused digital agency Qumin, points to a ban on price discrimination through unscrupulous marketing tactics like sha shu that offer first-time shoppers lower prices than long-time customers, which he thinks will make a more immediate impact on the companies’ revenues and stock prices.

Cleaning up fraud and protecting consumers

Even so, both Ma and Brennan find claims that Beijing is cutting down firms like Alibaba unfounded (when asked about Jack Ma’s reported disappearance and re-emergence, the latter deemed Western media’s reactions “overblown.”) “Alibaba’s going nowhere,” says Brennan.

Like anti-trust, restricting data practices has been a long time coming: while consumer anxiety around privacy has been on the rise for years, many Chinese platforms still make access to their apps and services conditional on users providing personal information. Companies have historically “done whatever they want with data,” says Arnold Ma.

Chinese mobile users commuting in Beijing. Shutterstock

Both Arnold Ma and Rui Ma expect China to follow Europe’s lead with GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation); rather than collecting less data, the law will likely be focused on transparency, consent and conscious usage. Though what that looks like in practice remains to be seen, Rui Ma predicts that the low-hanging fruit — going after fraudulent data abuses and breach of personal information, for example — will be regulators’ first priority. “Data abuses are so rampant and there’s so little punishment that they can’t jump to something highly regulated.”

The same can be said for livestreaming, a multi-billion dollar industry that experienced rapid growth in the wake of Covid-19. Tmall’s livestream function has drawn celebrity fashion and beauty moguls Victoria Beckham and Kim Kardashian West, not to mention top brands Ermenegildo Zegna and Valentino.

But livestream hosts paying for fake traffic and purchasing bot accounts to boost traffic is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to deceptive practices, where excessive tipping, the main focus of last year’s rules, has been linked to crimes like money laundering.

Days after tech giant and search engine provider Baidu announced its intention to acquire livestream platform YY last November, due diligence investment firm Muddy Waters Research reported that “YY Live is about 90 percent fraudulent”; a month later Shanghai-listed cable maker Sunway put its purchase of a 40.27 percent stake in livestream player Chengdu Xingkong Yewang Technology on hold. While it is unclear what future livestream regulations will look like, criminal usage is clearly regulators’ most pressing concern.

Diversification of sales and marketing channels

As the anti-trust clampdown aims to level out China’s e-commerce playing field and drive growth for smaller firms, Rui Ma expects it to provide brands with multiple viable channels, thereby decreasing costs and upping efficiency.

“Competition between platforms will be a good thing for them,” Brennan says, noting that global brands have consistently complained about only having a few viable e-commerce channels to Chinese shoppers. “It’s an open secret in the market that things like forced exclusivity [agreements] have been a reality for brands for many years.”

Indeed, few brands have managed to get by in China without allying with a local retail giant. Even Gucci, which years ago expressed doubts due to the prevalence of counterfeits on Chinese online marketplaces, relented and launched not one but two Tmall flagship boutiques last December.

If brands aren’t worried about relying too much on one platform, they should be.

The years-long dominance of marketplace giants has stifled growth for smaller upstarts and made brands financially and operationally dependent on their platform for exposure and data — a precarious position to be in. “If brands aren’t worried about relying too much on one platform, they should be,” says Arnold Ma. When diligent brands do take it upon themselves to reclaim ownership, he predicts that rather than branching out into own-brand websites, a larger focus will be placed on social media, social commerce and brand-owned content formats. Brennan reckons that WeChat, in particular, stands to benefit from this shift.

Though the new restrictions on tipping are expected to hit platforms and livestream hosts’ wallets, Rui Ma doesn’t see them affecting brands. Though the anti-trust and data protection regulations could add friction for brands in the short-term, she expects that they’ll boost innovation and confidence in China’s e-commerce industry in the long run — after getting over short-term operating expenses and headaches, that is.

“[Data privacy regulation] will only affect brands if they rely [on Alibaba’s platform and data] to understand their customer, which I don’t think brands should be doing anyway,” said Arnold Ma.

Indeed, brands working with the likes of Alibaba have access to a wealth of consumer data, the breadth of which may be affected by incoming regulations; Brennan, for one, reckons that the accuracy of platforms’ consumer targeting tools may be reduced. At the same time, such platforms are often “walled gardens” in that data is siloed between them — a long-running inconvenience for brand partners — meaning a new data collection regime could, he says, make it easier for brands to apply findings from one platform to their account on another. It will also encourage brands to develop their own data capabilities, which will be increasingly valuable in China and beyond.

Likewise, a more fragmented market in the wake of anti-trust reforms could force brands to rethink their strategies, and casting a wider net across e-tailers will ultimately have its benefits. “It might be more operationally complex for brands, but my impression is that small brands all hate the [current dynamic],” says Rui Ma, adding that larger brands have more leverage to negotiate better terms with dominant marketplaces.

What should brands do to be better prepared?

Though it’s impossible to predict what China’s e-commerce market will look like after Beijing has ticked off its regulatory to-do list, there are things brands can do now to be better prepared.

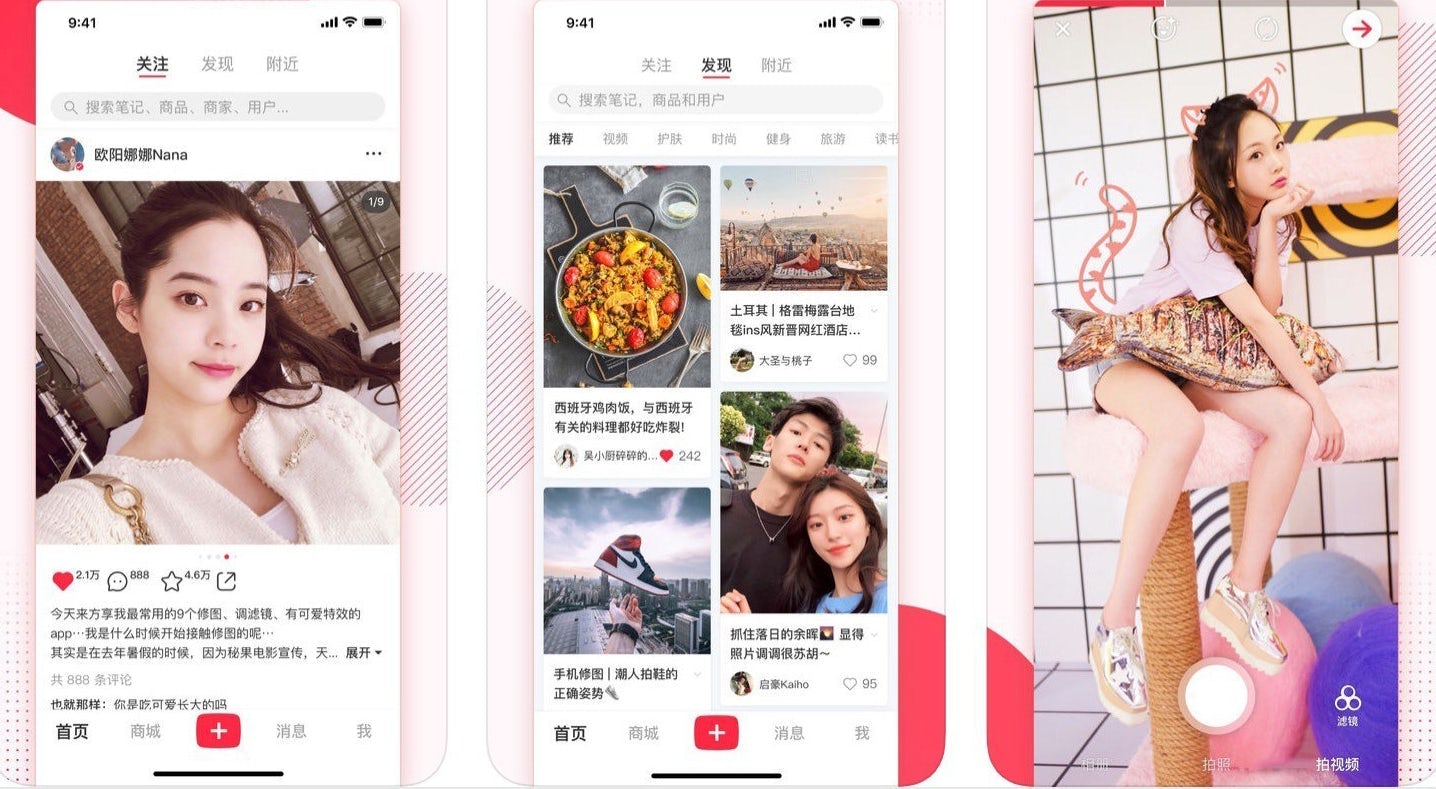

Arnold Ma recommends brands strengthen their presences on social media apps like Xiaohongshu and Douyin while bringing content streams in-house. Community is key: whether its skin care and makeup tutorials or live workout classes, building loyalty on owned channels (as opposed to through promotions on marketplaces or posts on KOLs’ accounts) will increase leverage and agility.

Xiaohongshu’s user interface. Xiaohongshu.

“Brands will learn quickly that they don’t have to rely on Alibaba to be successful,” he adds. “It’ll open more opportunities for them to do more multi-channel funnels, integrate data across platform and own their customers.”

When it comes to owned channels, WeChat, in providing brands with mini programmes, in-app stores and private traffic chat groups, will be essential for brands looking to reclaim control over sales, says Brennan. The Tencent-owned firm had a great 2020: it facilitated around $250 billion in transactions through mini programmes, a feat in its attempt to take a bigger slice of China’s online shopping market.

Brennan notes that unlike marketplaces, WeChat, in replacing the role of the web browser in China, doesn’t put an algorithm between brands and consumers, doesn’t fit into the same regulatory box and has a lighter touch when it comes to monetisation. “It’s hard to argue they are acting in a monopolistic manner,” he says. “WeChat is a different game.”

Ultimately, global brands should welcome the changes and take them as an opportunity to rethink their China strategies, suggests Rui Ma. “[Regulators] are not trying to make life difficult for brands coming into China,” she said. “If anything, they want more of that.”

Moreover, what happens in China could have far-reaching implications and prepare brands for changes to come in other economies. “Few people agree with how China regulates the internet, but it’s undeniable that they’re a bellwether for future trends,” says Brennan, predicting that what Chinese regulators impose will somehow inform approaches in Europe, the US and other Asian countries, though each market will take its own approach.

“Whatever happens, other markets will be looking at this closely.”

时尚与美容

FASHION & BEAUTY

Unilever offices in Rotterdam, Netherlands. Shutterstock.

Unilever Forms New China Partnership to Tap Premium Beauty Market

The British consumer goods giant, which owns brands from Dove to Hourglass, has formed a joint venture with Hangzhou GoLong Holding Co, coined Go-Uni, to develop new high-end beauty brands for the lucrative local market. The move signals a wider move towards premiumisation, which has seen not only Unilever but the likes of Shiseido favour premium brands over mass-market labels. GoLong has a track record of helping global beauty brands grow in China’s competitive beauty space, which is increasingly dominated by local companies: it has partnered with over 50 brands including Dermalogica, Kate Somerville and Korea’s SNP. (CBO)

Blackstone, Carlyle in the Running Against Chinese VCs for Fancl Distributor

The American private equity behemoths made bids for the distributor of Japanese preservative-free beauty brand Fancl in Asia excluding Japan in an auction last Friday, said people familiar with the matter. This put them up against Sequoia Capital China and Citic Capital in an auction that narrowed down to approximately $700 million to $900 million; Fancl’s current Hong Kong-based distributor CMC Holdings has yet to select one or more of the bidders to make a binding bid. According to the sources, Chinese giants Tencent Holdings and JD.com are among the companies looking to partner with the winning firm and boost sales in the mainland. One of the challenges facing the winning bidder is tackling Fancl’s wholesale network, where products are currently being sold at a steep discount. (SCMP)

Chinese Drive Sales as Auction Houses Embrace Luxury Fashion

The pandemic has pushed auction houses to appeal to a wider audience by selling sought-after Hermès handbags and rare Nike sneakers. This seems to be working among China’s young and affluent consumers, particularly since auction houses shifted online. According to Josh Pullan, managing director of Sotheby’s global luxury division, while Chinese online bidders have tripled from 2019 (outpacing growth in all other geographies), the number of online luxury sales made to Chinese buyers grew twelve-fold over 2020. KOLs are helping push this growth: Tao Liang, known as Mr Bags, brought his followers along to live auctions last December, where he bet on and won a Hermès Birkin for HKD $80,000 (around $10,319). (Jing Daily)

科技与创新

TECH & INNOVATION

2020’s Spring Festival Gala. CCTV.

Pinduoduo Ousted from Spring Festival Sponsorship

The group-buying marketplace was replaced by short video platform Douyin as the sponsor of China’s annual televised Spring Festival gala, which in 2020 garnered 1.23 billion views. Netizens began boycotting Pinduoduo and requesting the company’s removal from the program after an employee died from being overworked in December. Pinduoduo made no comment on the incident until a friend of the former employee spoke out on an online employment platform and the post was subsequently blocked; on Q&A site Zhihu, the company’s official account responded to queries by saying that people working for better lives would need to pay with their health. The incident outraged Chinese netizens and has heated up the discourse around the country’s infamous “996” (9 am to 9 pm, 6 days a week) work culture. Pinduoduo pulled out of the sponsorship as a result and on January 16 was replaced by short video player Douyin. (China Marketing Insights)

Kuaishou Eyes $5.4 Billion in Biggest Tech IPO Since Uber

The short video platform is reportedly preparing to list on February 5. Kuaishou, which is backed by WeChat owner Tencent, rose to popularity when it became a hub for content from content creators living in China’s rural areas. The platform now makes most of its revenue (over 60 percent) from livestreaming. If all goes according to plan, the share sale will be the world’s largest since Uber’s $8.1 billion IPO in May 2019. Alongside TikTok creator Bytedance, Kuaishou’s rise threatens the dominance of tech and retail giants like Alibaba; despite reports of a $2 billion IPO last year, TikTok’s troubles in the US (among other markets) has set it back. (Bloomberg)

消费与零售

CONSUMER & RETAIL

The Bund, Shanghai. Freeman Zhou.

Shanghai Residents Top Disposable Income Ranks

People in China’s fashion capital had the country’s largest purchasing power last year with an average of $11,182 per head, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. Shanghai residents were also the country’s biggest spenders, expending $6,582 each. Meanwhile, people in Beijing had an average disposable income of just $10,744. Overall, disposable income per capita rose 4.7 percent year-on-year, a vote of confidence towards consumer sentiment in the world’s biggest luxury market. (Yicai Global)

Behold China’s New Edible Beauty Trend

Chinese consumers looking for novel ways to live a healthier lifestyle are being offered a new kind of beauty product: beauty and skin-boosting snacks. China’s edible beauty market could be worth $3.7 billion by 2022 and in 2019, edible beauty sales on Tmall were growing 2,000 percent year-on-year. Local brands have already experimented with the pairing: C-beauty player Chando partnered with snack brand Pejoy to launch a mask and biscuit bundle (both products contain skin-brightening ingredient niacinamide); supplement brand Xiaoxiandun and ice cream maker Chicecream, meanwhile, created an ice cream with bird’s nest — a collagen-rich and anti-ageing ingredient according to traditional Chinese medicine. (Jing Daily)

政治、经济、社会

POLITICS, ECONOMY, SOCIETY

Now more than ever, cross-border investment is a high-stakes game | Illustration: BoF

China Overtakes US as Destination for Foreign Investment

China took the US’ spot as the top country for new foreign direct investment, according to a report by United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), due in part to a sharp drop in new investments into the US from overseas companies in 2020. Compared to the US’ $134 billion in investment, China raked in $163 billion during 2020, up from $140 billion the year before. Though the US is still in first place when it comes to total foreign investments, the news signals China’s increasingly pivotal role in the global economy. It is expected to leapfrog the US and become the world’s biggest economy by 2028, according to UK-based think tank Economics and Business Research (CEBR). (BBC)

How Chinese Netizens Reacted to the Biden Inauguration

Last week’s inauguration was livestreamed by China’s state broadcaster CCTV and drew a litany of comments online. Users joked about the note Donald Trump reportedly left his successor (“The note reads: ‘Wifi password is 88888888,” one wrote) while others lamented Trump’s departure (“Farewell, king of comedy,” posted another.) Many Weibo users commented on the tough job facing President Biden, while some warned that US-China clashes are far from over (“A wolf was sent away, and a tiger came in. Biden’s attacks on China will be worse than Trump’s!”) Though it remains to be seen whether they will be proven true, experts, too, expect Biden to take a tough stance against Beijing. (SupChina)

Meet Beijing’s Influencer in Chief

Chinese sportswear giant Anta has long nurtured ambitions to overtake Nike and Adidas in its home market. While the group, which owns the likes of Arc’teryx and Fila, currently holds a 15 percent market share, the upcoming Winter Games and a boost by an unexpected KOL could give it a boost. President Xi Jinping sent the company’s stock soaring after he was spotted in the $1,000 Arc’teryx Thorsen Parka while inspecting the 2022 Winter Olympics and Paralympics site Tuesday. Hong Kong-listed Anta Group saw its stock jump 9.4 percent on the same day. The group is the official sponsor of the 2022 games and has dressed China’s Olympic team for the last eight years. (Inkstone)

China Decoded wants to hear from you. Send tips, suggestions, complaints and compliments to our Shanghai-based Asia Correspondent [email protected].

:quality(70):focal(1001x691:1011x701)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/businessoffashion/RPF42J4GTREGNH4QEBE3ZDXJA4.jpg)