Climate Transformation that Sticks | Newsroom

Comment

The Climate Change Commission’s advice offers a blueprint for transformational policy that sticks, Marc Daalder writes

After a term of government somewhat constrained by Winston Peters on the handbrake, Jacinda Ardern is used to accusations of not being “transformational” enough.

In response, she’s developed a tried and true philosophy, one she repeats whenever challenged on the ambition of her Government: “Transformation is change that sticks”. That may mean it doesn’t occur as quickly as some would like or upheave old norms to the degree others are after, but that it remains in place not just years but decades after its advent. Incrementalism that lasts.

That philosophy can be found in the form of the Zero Carbon Act, which created an independent and non-political Climate Change Commission to provide expert advice on the climate crisis and recommend progressively shrinking emissions budgets – limits on how much the country can emit in successive five-year periods. The Commission was endorsed by every party in Parliament save ACT. In fact, the Commission was the element of the Zero Carbon Act National most strongly supported.

In other words, the Commission is the sort of change that seems likely to stick around.

That’s why it was so significant when the Commission released its first batch of advice – including proposed budgets for 2022-2025, 2026-2030 and 2031-2035 – on Sunday and called for “transformational and lasting change across society and the economy”. If the Commission is here to stay and if it supports true transformation – not incrementalism – then maybe Ardern has indirectly achieved transformation that sticks.

Will it stick?

For that to be the case, two things must be true: The Commission must garner not just cross-partisan support but also the support and buy-in of the general public and it must maintain that support even as it recommends the transformational action needed to reduce emissions in line with 1.5 degrees.

On the former front, almost every reaction to the Commission’s landmark report contained praise for the evidentiary base it had constructed and the overall mission of the Commission itself.

Read more:

* Key takeaways from the Climate Change Commission’s advice

* Newsroom’s in-depth analysis of the Commission’s report

Even those elements most historically opposed to radical action offered words of support for the broad conclusions arrived at by the Commission – that New Zealand is set to miss its emissions reduction targets and that the tools and technology needed to meet those targets already exist if the country engages in “strong and decisive action now”.

“The Commission has offered sound, depoliticised advice for agriculture emissions that acknowledge New Zealand’s world leading low emissions footprint,” Federated Farmers conceded. (Compare that to this line, from when the then-Zero Carbon Bill emerged from select committee: “The government has missed a golden opportunity to take its farmers along with them. We will keep working to achieve lower emissions, but the pressure of this unattainable goal will eventually weigh heavily on some farmers.”)

“While we don’t agree with every proposal, this is a thoughtful and nuanced report,” the chief executive of Petroleum Exploration and Production Association of New Zealand John Carnegie said.

“The Motor Industry Association welcomes the Climate Change Commission’s draft report into required pathways to reduce New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions. It is a significant contribution to the debate and documents the challenge ahead for all New Zealanders,” the auto group offered. (Compare that to the headline of a statement from just three days earlier: “MIA has concerns at the speed of CO2 targets for vehicles entering NZ.”)

In politics, National’s climate change spokesperson Stuart Smith similarly welcomed the report. “National supports New Zealand playing its part to combat climate change and we acknowledge the hard work of the Climate Change Commission in producing the comprehensive analysis released today,” he said.

None of this indicates there is complete and absolute support for the work of the Commission. Carnegie warned against the proposal to ban new natural gas connections from 2025 while Judith Collins has begun to raise doubts about whether the Commission’s estimate of the economic impact of taking action is accurate.

At the same time, the desire from all sectors to be seen agreeing with the general direction of travel – towards a low-emissions economy – is refreshing. It also indicates awareness that climate action is in vogue – consumers and voters want to make choices that not only benefit them but the environment as well.

However, potential backlash against the report is also brewing. The proposal for an end to new natural gas connections and the efforts to decarbonise transport (read: no more diesel double-cab utes) could easily be weaponised to delegitimise the Commission’s findings and recommendations. Keeping the public on-side is important and will require genuine outreach.

The Climate Change Commission has engaged in some of this outreach on its own, with regular Zoom webinars breaking down complex science and the call for submissions by March 14. But Commission chair Rod Carr is right to call for a much larger public information campaign.

While most New Zealanders say they care about climate change, they don’t really understand it. Nearly three in five Kiwis say recycling is one of the most effective climate actions they can take (it really has a negligible impact on warming) but just two in five think the same about driving their fossil fuel car less. In order to garner support for transformation, the Government needs to ensure New Zealanders understand why they may be asked to walk or cycle instead of drive or why they should use less natural gas – just like the Government excelled at explaining why social distancing and lockdown were needed to ward off the Covid-19 pandemic.

Is it truly transformational?

Of course, the second component for transformation that sticks is ensuring that the change is truly transformational.

There is broad agreement that the reductions of long-lived gases – primarily from the transport, energy and industry sectors – called for by the Commission are ambitious. Net carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide emissions would fall by a third in the next 10 years compared to 2018 levels and nearly halve from there over the subsequent five years. Come 2035, New Zealand would emit just 13.1 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent per annum in net long-lived gases, compared to 36.3 in 2018.

However, the Commission’s report has been criticised by some environmental groups for failing to crack down hard enough on agricultural emissions. While emissions from transport, power and industry will have to fall by more than 45 percent by 2035 under the Commission’s budgets, long-lived agricultural emissions would reduce by just 16.4 percent by the same date.

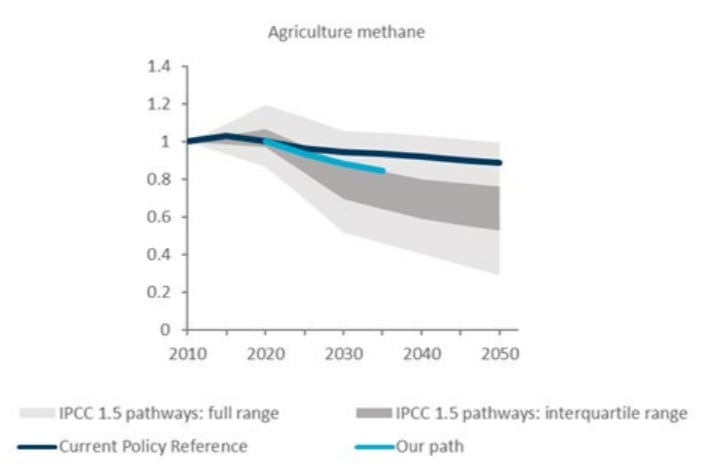

Biogenic methane from agriculture would also have to fall just 17.7 percent by 2035.

That’s all for good reason. Methane doesn’t need to reduce to net zero to achieve the desired halt of global warming, although steeper reductions do help to reduce warming impacts more quickly.

Moreover, the Commission based its budgets on currently available technology for reducing emissions in line with a pathway that limits global warming to 1.5 degrees above preindustrial levels. For most industries, it also attempted to limit the economic damage of the transition. In agriculture, although the Commission’s pathway does involve reducing herd sizes by around 15 percent by the end of the decade, total milk and meat production would remain flat or even slightly increase over the same period.

That reduction, alongside the use of other farm management practices and the proven method for selective breeding for low emissions sheep, would see biogenic methane drop 13.5 percent in a decade and 17.6 percent by 2035, compared to 2018 levels.

I disagree with those who say the Commission’s agricultural targets lack ambition. In fact, what makes them so potentially transformational is that same reliance on existing technology, because it opens the door to steeper cuts as new tech develops.

In the Commission’s view, the 17.6 percent mark is not just a target to reach before halting reductions – it’s a minimum reduction. The report specifically calls on the Government to overachieve and the Commission drafted its budgets with the full knowledge that new technology to reduce methane emissions from agriculture is likely to emerge in the coming years.

If that new technology does emerge, it doesn’t mean the primary sector will be able to put off the herd reductions and use the tech to reach the Commission’s benchmark. It will instead be expected to engage in deeper cuts more quickly than the Commission recommended. When the Commission next reviews its budgets – which happens every five years – it can create new, more stringent targets for biogenic methane in light of the new developments.

Despite primary sector lobbyists saying the Commission’s targets can only be met with new technology, the advice is clear that new technology would create new responsibilities to reduce emissions. With the current tools available, the Commission expects New Zealand would just barely scrape the less ambitious end of the 2050 methane reduction range.

However, “developing and widely adopting new technologies to reduce livestock methane emissions would enable Aotearoa to reach the more ambitious end of the 2050 methane target range”, the Commission found.

Why call for further reductions if the existing targets are consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 degrees? Because the pathways for 1.5 degrees are estimates from complex models that don’t produce specific targets but rather ranges and probabilities.

Devised by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 1.5 degree pathways can involve no, limited or higher overshoot beyond 1.5 degrees, and have various probabilities (often a 50 or 66 chance) of achieving this target.

That means reducing methane by 17 percent by 2035 doesn’t give us a 100 percent change of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees. Any further reductions we can make in any sector will only better our chances of averting catastrophic warming and if new opportunities present themselves, they should be realised as supplementary reductions on top of what is already planned.

That’s especially important for agriculture, where the Commission’s budgets just barely fall within the middle 50 percent range of the 1.5 degree IPCC pathways. As the chart below shows, other gases and energy sources are much closer to the midpoint.

There’s always the danger that the sector uses technology to offset the need to reduce herd sizes and chooses to aim for the 17.6 percent minimum reduction instead of overachieving. But that’s where the public and institutional buy-in to the Commission’s programme comes in – popular and political pressure can force a reversal, ensuring the spirit and not the letter of the budgets is followed.

If emitters heed the Commission’s recommendations and reduce emissions in line with the budgets while seeking out further opportunities to further cut greenhouse gases, then the transformation occurs unopposed.

Either way, it’s transformation that sticks.