‘We’re all hip-hop family’: the artists fighting to get Afghan breakdancers to safety | Global development

A veteran of the hip-hop scene and internationally celebrated breakdancer, Nancy Yu – AKA Asia One – has her fair share of people contacting her looking for advice. But the message she received in 2019 from a young Afghan was a little different.

Frustrated by his breakdancing crew’s inability to get visas to perform internationally, Moshtagh* was wondering if Asia could help. “He felt they were really good, but they felt, like, invisible to the world,” she says. “I liked him. He wasn’t trying to bug me or say ‘we need this right now’ … He seemed rather humble and honest.”

Over the months, a friendship grew between Kabul and California, based on mutual respect and an appreciation of hip-hop culture. Moshtagh, who is in his 20s, felt he had a lot to learn from Asia, a one-time member of the Rock Steady Crew who set up the B-Boy summit, a global gathering celebrating all the elements of hip-hop: breakdancing, DJ-ing, rapping and graffiti.

Only once has her belief in Moshtagh’s humility been severely challenged: when he declared, with youthful bravado, that he could be better than Tupac Shakur. “I was, like, ‘you’re out of your mind’,” Asia laughs.

Last year, as the Taliban made sweeping gains across Afghanistan and even the modest freedoms enjoyed by many young people in Kabul started to feel in doubt, Moshtagh’s messages became more serious and urgent. And in the summer, as the Taliban took the capital, came the decision: the hip-hoppers, he told Asia, were leaving.

It was a decision “based on complete fear”, says Asia. “You know, just that overwhelming sense of survival, that ‘if we don’t leave now, we don’t know what’s going to happen to us. And so we’re gonna risk our chance’. Because … they felt so threatened by the Taliban based on their western practices.”

Now Moshtagh was asking his American mentor for different help: “He said, I feel like you guys have an obligation to help us and I was like, what do you mean?” she recalls. “And he said, well, you know, we’re all just hip-hop family. And … the more and more we spoke, the more and more I realised that much of what he was saying was true.”

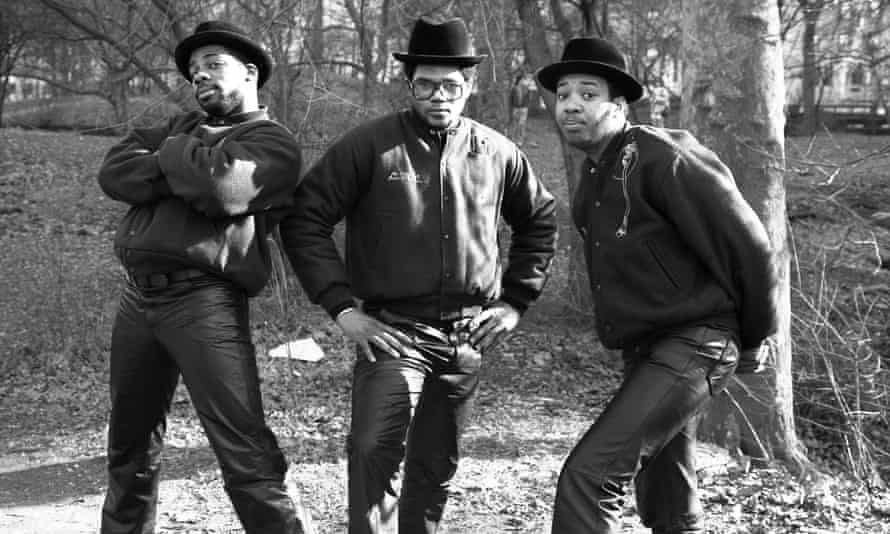

Ever since hip-hop first erupted in the Bronx apartment blocks of 1970s New York, its social conscience has never been far away. From the daily struggles of black America to the war on drugs to police brutality, there is little about life on the margins that hasn’t been rapped, sprayed on walls, chanted at rallies. (During the summer of 2020, it was a 1989 Public Enemy anthem that echoed at many of the protests over George Floyd’s murder. “Gotta give us what we want./ Gotta give us what we need./… We’ve gotta fight the powers that be.”)

In the era of billionaire rappers and ostentatious bling, it can be easy for that activist spirit to get lost. But for Asia, who heads No Easy Props, a nonprofit running hip-hop events and classes for marginalised communities in Los Angeles, it is intrinsic to the scene and partly why she felt touched by Moshtagh. “It awoke my thought process. Here are some people that feel invisible. And hip-hop was started by a group of people that felt invisible,” she says. “To me, not being able to practise hip-hop is one thing, and not being able to live is another thing,” she says. Within days of his request for help, she started to mobilise.

Moshtagh is a mild-mannered man in his 20s whose spoken English is heavily flavoured by hip-hop. He speaks of “homies,” of “breakers”, of “B-girls” and “B-boys”. As a teenager in Hamid Karzai’s Afghanistan, he fell for the moves he saw in videos of breakdancers from far away, and set about trying to become just like them – perhaps even better.

In a country that retained a deep social conservatism long after the Taliban were toppled in 2001, it was not an easy path.

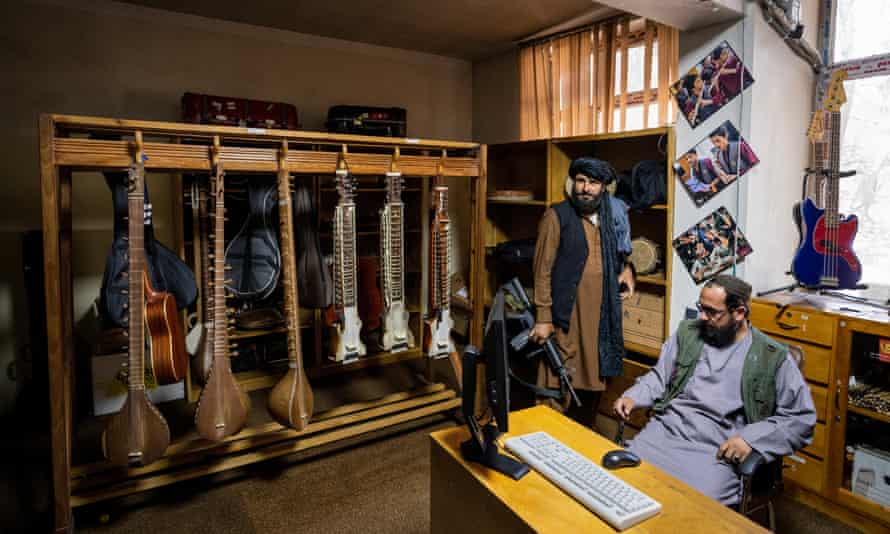

“People didn’t accept hip-hop,” says Moshtagh. “They were just thinking that this has music: ‘it’s haram, you can’t do it, it’s illegal. What is this western culture that you guys are promoting?’ But we were just thinking we are modern people; young people need to look for modern things, and we love to do this.”

Despite disapproval and threats, he and his friends made progress. “We changed people in 10 years but everything fell apart,” he says. “That building that we built, actually, it’s destroyed. There’s nothing for us to do in Afghanistan any more.”

On 18 August, three days after the Taliban overthrew Ashraf Ghani’s government, Moshtagh left Afghanistan, along with some of his “homies”. They have been in a neighbouring country ever since, trying to remain hopeful butconstantly worrying about the future.

“Actually, we don’t care about ourselves that much,” says Moshtagh, via Zoom, his five-year-old sister bobbing up and down in the background. “We’re just thinking about our family members. We don’t want them to be in a hard situation because of us, because of what we were doing. It’s all on our shoulders.”

According to Menno van Gorp, a Dutch breakdancer with more than 100,000 Instagram followers who has been in touch with him for years, Moshtagh “is a guy that carries a lot of responsibility for the people around him … He’s the one that keeps the wheel spinning.”

Alongside Moshtagh, there are 19 in the group, including two children and six women. A mixture of breakdancers, rap artists, parkourists and family members, they feel there is no place for them in Afghanistan today. “I’m sure they [the Taliban] would not accept it. There’s no space [for it],” he says. Some of the group have openly criticised the Taliban. Adding to the group’s fear is their ethnic background: all but three are Hazara, the most discriminated against minority group in the country.

For one of the dancers there is the additional complication of being a woman. Before leaving Kabul, Haleema* had been hoping to compete in the 2024 Olympics – the first to have breakdancing as an official sport. When she first saw videos of people doing it she thought it must be “a kind of Photoshop” but she trained hard, and received threats to her life for doing so.

But she knew she could not continue under the Taliban: the group have made their opposition to female sport clear, and breaking has the additional stigma of also being a form of dance. So inextricably connected is Haleema’s life to hip-hop, she, too, decided to leave. She insists it was not a difficult decision. “I am very young,” she says. “At my age, there is no impossible.”

Van Gorp says that for years, amid chronic national instability, hip-hop gave Moshtagh and the others sanctuary. “Breaking was the thing that kept them sane,” he says. “Like, they call it ‘hip-hope’ instead of hip-hop.”

Even now, in limbo, unable to go out, Haleema still dreams of competing in the Olympics. “I am just trying to find a way to get out, and to train,” she says. “I’ve got hope for the future because of the people that are helping us.”

By last autumn, Asia One had built up a small but dedicated team for the #SaveAfghanHiphoppers mission. “Hip-hop culture is about giving back, so let’s help our community members in need,” reads the campaign website.

They raised nearly $14,000 (£10,000) to cover the group’s basic needs such as food, clothing and shelter, as well as initial legal costs. But time is ticking on, and the costs are likely to mount, so the campaign is keen for people to donate.

Nearly six months after they fled, the group is still hoping to be granted passage to a country that will give them asylum. For now, the hip-hoppers, many without passports, remain in hiding lest they are arrested and deported back to Afghanistan.

“If we raise $50,000, we can get them out of there,” says Asia. “We think it’s actually very possible.”

The mission’s lawyer, Jaclyn Fortini Laing, is working to find a country willing to take the hip-hoppers. The US and the UK, both key to Afghanistan’s recent history and global hip-hop culture, have proved dead ends.

That’s a shame for the group and the countries in question, says Fortini Laing. “The ideals that [the hip-hoppers] stand for – freedom of speech, women’s rights – are the ideals that make them a target for the Taliban but would make them an asset to any other country that was willing to take them in,” she says.

“Failure,” she says, “is not an option.”

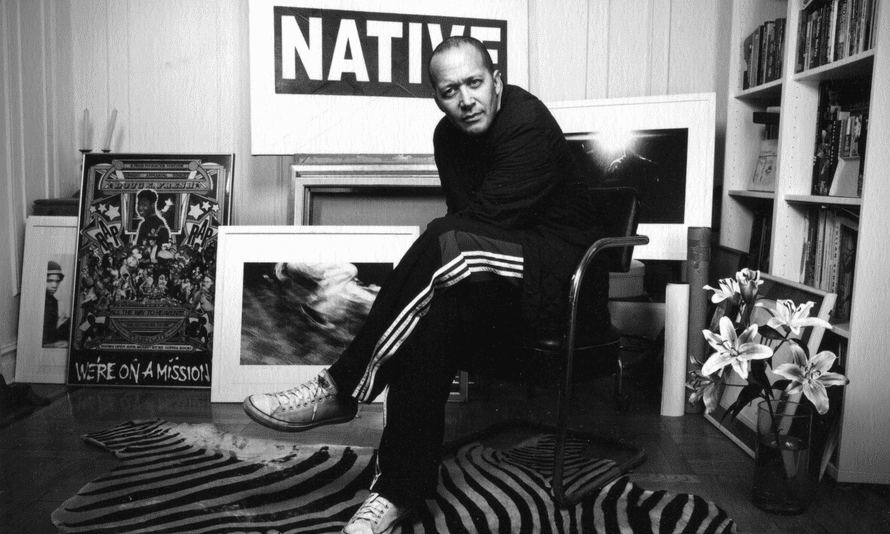

Equally determined for the mission to succeed is Michael Holman, a pioneer of hip-hop’s first wave who has gone on to have an eclectic career as a Broadway producer, film-maker and musician. When Asia rang around to see who might be willing to help the Afghans, he was one of the few who said yes.

“I was like, I can’t say no,” he says.

Holman, 66, is believed to be the first writer to have used the phrase “hip-hop” in print: in a 1982 interview with Universal Zulu Nation’s DJ Afrika Bambaataa for the East Village Eye, he defines “the all-inclusive tag for the rapping, breaking, graffiti, crew fashion wearing street sub-culture”. (Elsewhere in the article he rhapsodises about an evening at the Ritz where Zulu Nation “threw down” a Rolling Stones track: “Honky Tonk Woman never rocked so hard!”)

Heavily involved in the early days of Grandmaster Flash and the Beastie Boys, Holman helped introduce the “park-jam culture” that had emerged uptown to downtown Manhattan, and then to the world. In 1981, he took Malcolm McLaren to the Bronx to see what all the fuss was about and, “blown away”, the former Sex Pistols’ manager asked him to put together a show featuring Jazzy Jay and Rock Steady Crew.

Holman built an extensive archive of video footage, partly from his short-lived TV show, Graffiti Rock; films from the dawn of hip-hop that went all over the world. “[They] were horrible copies,” he says. “But those tapes were how these dancers learn how to dance around the world.”

So he felt duty-bound to help. “I felt I owed them something,” he says. “I was a mentor, in a way, by spreading this culture, and they embraced it because I and other people like me made it a compelling, exciting and undeniable cultural thing. I now owed them something. I had a responsibility not only as a hip-hop pioneer and impresario but I now owed them something as an American.”

Moshtagh has many questions for the US, widely criticised for its rushed, chaotic departure from Afghanistan. Questions, too, for the UK, which supported its 20-year mission. “Your countries came to Afghanistan to bring peace; you spent a lot of money … And now you left these people alone. Why don’t you care about them?” he asks.

He doesn’t know where he will end up. Spain or Belgium appear the most likely candidates, but the process is bogged down in diplomatic negotiations. Van Gorp, in Rotterdam, is optimistic that, wherever they go, there will be a community ready-made for them.

“Breaking is such a good bridge to connect with local people because it’s so open and welcoming,” he says. “It will really help them settle. So, like, wherever they will go there will be B-boys they can connect with and they will already have a small network.”

Moshtagh doesn’t know if he will see Afghanistan again. He wants to be in a safe place. “It doesn’t matter [where]. This Earth is my home. Earth is for human beings,” he says. Haleema just wants the agonising uncertainty to end. “[In] real life, you’re free to do all the things that you want,” she says, simply. “I want to live free.”

* Names have been changed

Sign up for a different view with our Global Dispatch newsletter – a roundup of our top stories from around the world, recommended reads, and thoughts from our team on key development and human rights issues, delivered to your inbox every two weeks:

Sign up for Global Dispatch – please check your spam folder for the confirmation email