‘Waste Is Only Waste When You Waste It’ – Could Ecobricks Be The Solution To Uganda’s Housing And Pollution Problem?

About 40 kilometres out of Uganda’s capital, Kampala, in the Mpigi area, you can find an entire village hill with houses that have plastic bottles walls and car tyre rooftops.

Plastic bottles, which you can usually found littered almost everywhere in rural and urban Uganda, could help alleviate the country’s housing shortage as well as avoid environmental harm. An innovative idea of turning plastic bottles into “ecological bricks” is one of the latest solutions being promoted by environmentally sensitive individuals and NGOs here.

The village in Mpigi is part of a project by the Social Innovation Enterprise Academy (SINA), which promotes the use of ecobricks as an upcycling solution to the plastic waste problem rather than reverting to recycling.

- Recycling would involve the waste being reduced or destroyed from its current form to create something new. Whereas upcycling uses the existing waste and incorporates it into something new.

The initiative has spread out to a number of refugee camps in Uganda.

Uganda’s plastic headache

Like many other African countries, Uganda is faced with the threats of plastics arising from the packing and beverages industry.

The plastics from bottled soft drinks end up in landfills, scattered all over the streets and block roadside drainage. Most of the plastics waste has been found floating on shores of Lake Victoria, it’s swamps and wetland or are simply burnt in the open air.

It is estimated that Kampala, the country’s capital, alone generates more than 350,000 tons of solid waste every year, only half of which is collected. So plastic remains one of the huge environmental concerns for the country whose plastic consumption increases by the day.

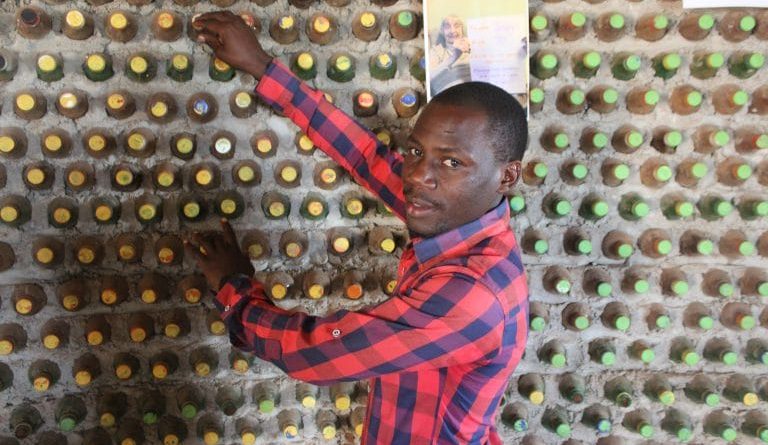

David Mande is a promoter of the ecobrick solution. He works as a builder and a trainer at SINA. The plastic waste have huge significance for him. Mande’s younger brother died tragically after trying to cross a swamp. After several hours of searching for the dead boy, his body was found concealed under a pile of bottles.

“I need to make use of these bottles. I found out that in Nepal and Nigeria, they were using those bottles to build houses in rural communities. And it has worked too in Uganda,” he told IPS.

He has become an enthusiastic promoter of upcycling plastic bottles instead of recycling.

The ecobricks, according to Mande, are filled with moist soil to ensure that they become hard. The bottle top is then tightly closed to ensure that the moist sand and soil bond to make a brick that can be turned into a strong wall.

Ultimately, Mande said, the aim is to maintain a green planet.

“So we collect the bottles and tyres from the environment and turn them into ecobricks and tiles. Then we use them for the construction of beautiful houses like the ones you are seeing across there,” said Mande.

Are ecobricks a solution to the country’s housing shortage?

Mande estimates that three million plastic bottles that were littering the environment have been used to construct some 117 houses across this East African nation.

Though it may take a while yet to alleviate the country’s housing shortage. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, the country has a deficit of 2.1 million housing units, growing at a rate of 200,000 units a year. It is estimated that by 2030, the country’s housing deficit is expected to reach in excess of five million units.

Edison Nuwamanya, who runs a shop from one of the houses constructed with plastic bottles or eco-bricks, told IPS that he had not seen these types of buildings until he moved to Mpigi area.

“Nature always provides the cool environment; it is rarely hot in here. It looks nice and it feels good to be in,” Nuwamanya told IPS of the house.

Back in Kampala’s Kamokya slum, a group of young people have turned plastic waste bottles to their advantage by promoting ecobricks as an alternative to mud and wattle houses common in this area.

The men and women from the Ghetto Research Lab collect plastic bags and bottles and repurpose them into ecobricks. From a distance one is welcomed by piles of bottles and polythene bags, which they use to make the bricks.

Rehema Naluekenge is one of the women involved constructing houses using the bottles. She uses a metal rod to staff soil and polythene bags into the bottle.

“I compact polythene bags and soil into the bottle until it gets hard. Because if the bottle remains soft as it was meant to be, it can’t make a brick,” she explained to IPS.

“The houses constructed with bottles or ecobricks are proving to be quite durable. We have not seen any develop cracks,” said Nalukenge. “Our operating principal at Ghetto Research is that waste is only waste when you waste it.”

The demand for Uganda’s plastic waste has dropped

It has been common to find huge heaps of plastics in urban areas, these are usually collected by women and children for recycling into plastic flake products, which would be exported to China and India.

Manufacturers in India and China would recycle the flakes into products like polyester fibres for cloth and carpets or back into plastics bottles. But the market seems to have dried up. A middleman who was supplying these plastic flakes to China told IPS that the closure of particularly the China imports has had huge blow to the recycling industry in Uganda.

“There is no demand from our usual customers. It is not a COVID-19 effect. China’s demand reduced [before the outbreak], followed by India in mid-October last year,” the middleman, who declined to be named, told IPS.

A kinder method of construction

In the central Ugandan district of Mukono stands another upcycling project — this one is by high school teacher Allan Obbo. Obbo is the owner of the Bottle Garden Resort, whose entire perimeter wall and a number of cottages have been constructed from waste bottles.

“Research tells us that plastics are very dangerous to the environment … look at our lakes, the lakes are choked. And research tells us that for this bottle to degrade, it will take 300 years.

“So if I use one for building, it has more life than when left in the soil. So using this bottle as an alternative for construction saves the environment,” Obbo told IPS.

“Construction materials are detrimental to the environment. When you get the bricks, sometimes you are using soils that you could have used for farming. Then on top of that you go on cutting down trees, but when you are using the bottles, you are retrieving them from the environment,” said Obbo

Obbo doesn’t know how many bottles he has retrieved from waste bins to construct his Bottle Garden Resort.

“I have one unit I took the time to count and it has 12,000 bottles. But if you put all the structures together, they are over a million bottles. It would have choked the environment,” he said

Lack of awareness and government support

While Obbo thinks that eco-bricks can serve as alternative building material, he told IPS that he was disappointed that construction engineers in the country’s urban areas cannot approve building plans for developers planning to construct houses using waste plastic bottles.

Obbo thinks recycling has not helped to retrieve all the bottles and that it cannot be comparable to upcycling.

“Remember recycling it into a reusable plastic, again there is that carbon emitted. And when that carbon goes to the ozone layer, it will affect the environment. With this one, there is nothing that goes in the air to pollute the environment,” he said.

Architect Patricia Kayongo, the managing director of Kampala-based Dream Architects Ltd., has been involved in supervision of construction projects in government and the private sector in Uganda.

She told IPS that while the ecobricks have not been tested and approved by the country’s bureau of standards, they, together with other buildings materials, can be used as a sustainable building solution.

“And not much research has been done on them. It means that people have been denied of more options for constructing houses cheaply,” said Kayongo.

She said recycled materials like glass and plastics are good for construction but they were not being utilised to solve the housing deficit in most countries.