The odd friends: The young liberal and the elderly conservative | US & Canada News

The waitress at Cracker Barrel looked confused when she stopped at our table. Among the snow globes, animatronic weasels, and ceramic pineapples, Richard and I were yet another random curiosity. A 30-something year-old woman in jeggings and a pixie cut next to her 92-year-old friend with the rodeo belt buckle and scraggly beard.

Richard flashed a gap-toothed grin at the waitress. “Hon, can you bring us one of them baskets? With extra biscuits?” he asked. He knows I like biscuits better than cornbread. At 92 with his sweet smile and wispy white hair, Richard’s “Hons” and “Sweeties” lack the demeaning quality they might have with a younger man in a position of power. Still, I studied the waitress’s face. I started to tell Richard not all women like being called “Hon,” but the waitress’s expression softened into bemusement. “Of course, Hon,” she said, then headed towards the kitchen.

In an era when the political is personal, people make assumptions about others’ beliefs based on their appearance. Many of the assumptions one might make about Richard are correct. He is a lifelong Texan and a white evangelical Christian who dropped out of school in the sixth grade. Like 55 percent of men with no college degree, Richard is staunchly anti-abortion rights. He has voted Republican since before I was born, including a vote for Donald Trump in 2016.

If Richard fulfils a stereotype, so do I. Like 51 percent of Americans aged 30 to 49, I supported Hillary Clinton. I identify as a feminist and an atheist. I earned my master’s degree from a music school on the East Coast. I organised watch parties for President Barack Obama’s election, donated to the Bail Project, and vote Democrat.

Once a week, a Facebook friend brags about ending a relationship with a friend or family member who voted for an opposing political party. I have blocked Republican friends myself, usually for posting memes or rants that incited violence or discriminated against marginalised groups. But Richard and I have been friends for eight years, despite openly discussing our ideological differences.

When the basket of biscuits arrived, Richard reached for one. Then his eyebrows shot up. His hand flew to his mouth. “I forgot my teeth,” he said, meaning his dentures. We laughed.

Leaving school at 12 and college degrees

I first met Richard in 2012 when he called me about violin lessons. To liberals, America in 2012 was a warm cocoon. Social safety nets like the Affordable Care Act told poor or sick Americans for the first time they mattered. Neo-nazis hid rather than marching down streets brandishing torches.

It was in this year that Richard, at 84 years old, decided to take up the violin. His wife had died in 2011, and he had recently found his grandmother’s violin in the attic. The local music shop had given him a list of teachers’ names and contact numbers. Mine was at the top.

At his first lesson, I handed Richard a copy of my policy and expectations for students. Nodding solemnly, Richard pulled a pencil out of his bag and took notes in neat cursive penmanship. He has practised nearly every day in the eight years and counting he has been my student.

More American millennials than any previous generation have college degrees. Like many people my age, I took for granted that my education would continue after high school. Higher education whisked me from my homogenous suburb onto a campus with peers who had different religions, abilities, ethnicities, cultural backgrounds, and sexual identities. My professors taught me to critically engage with the news, which influences my voting decisions today.

Richard, however, did not attend school past the sixth grade. One of the defining moments in his life occurred when at age 12, he asked his father for a nickel. “I haven’t got a nickel,” his father told him. “You want money, you go to work.” Shortly after, Richard left school and got a job “pearl diving” – washing dishes in a restaurant. He performed manual labour before enlisting in the army. Thirty years later, he retired from the light company where he had worked his way up to foreman.

Richard poses with his violin during a lesson [Photo courtesy of Meghan Beaudry]

Richard poses with his violin during a lesson [Photo courtesy of Meghan Beaudry]The Bible and speaking your mind

During that first year of weekly violin lessons, our conversations began to extend beyond the violin. I responded to Richard’s stories of his late wife, Beverly, with anecdotes from my own recent marriage. Richard reminisced about his military tour of Japan and Korea at the tail end of World War II. I learned to appreciate his sharp wit. Once, Richard mentioned a car he had seen that had crashed into the gates of a cemetery. “People are just dying to get in there,” he said dryly. With his mischievous smile, he looked like a schoolboy who had just slipped a toad into a classmate’s desk.

I first glimpsed how much Richard’s ideology conflicted with mine several months into our lessons. Richard had offered to take my husband and me out for dinner. We met him at Spring Creek BBQ. He wore cowboy boots and a giant silver belt buckle. Richard’s devout Christianity had never been a secret, but I hadn’t realised until then how much his religion influenced his politics. Perhaps I should have. Eight out of 10 evangelical Christians say they plan to vote for Donald Trump in 2020. Once seated, he questioned my husband and me about our nonexistent religious beliefs. “You need to think about what happens after you die,” Richard urged. Then he passed out anti-abortion rights pamphlets to random diners, who accepted them with polite but confused nods. The title: God Has a Plan for Your Child.

Richard would persist in his efforts to convert us for months. Years later, I would learn to see his determination for what it was: a strong desire to save a young couple he had grown deeply fond of, in the only way he knew how. But once during a lesson, I couldn’t contain my annoyance. “Are you here to learn the violin or not?” I snapped.

Richard paused. “I am,” he said. Then he looked at me with genuine curiosity and asked what exactly I had against the Bible. I thought of the priest at the church I had attended each week as a child – of the blistering sermons condemning gay people and women, but rarely men, who had sex before marriage. I remembered the time I had endeavoured to read the entire Bible as a teenager. I got as far as Sodom and Gomorrah before closing the book forever. What lodged in my developing brain was not the allusions to homosexuality, but a father who offered up his own virgin daughters to be raped by a mob.

“I don’t think the Bible treats women well. Almost all the stories in there are about men,” I told him. “I just don’t see myself in that book.”

Richard sat in silence for a moment. I hadn’t yet visited his house and seen the dozens of Bible verses embroidered, carved into wood, or painted in frames on his walls. I hadn’t seen the dog-eared King James version on his table, bright tabs and sticky notes poking out from the worn pages. When Richard spoke, he didn’t lash out. He didn’t defend the belief system that defined his life. He complimented me. “One thing I respect about you is you always speak your mind,” he said quietly.

Hurt and friendship

For several years, Richard’s and my opposing beliefs lay between us like a faded stain on the carpet. Present, but rarely discussed. The 2016 election dragged these differences from the periphery of our relationship to where they couldn’t be avoided.

Shortly after Trump’s victory, Richard and I went out for lunch. Like many liberals, the 2016 election had sent shock waves through my life. Our new president spewed hate and threats atop the most public platform in the world. To me, a woman with serious chronic health issues, many of these threats were not existential. They were life-threatening. I worried about the gay couples I knew. I worried about my friends of colour. Which is why I stopped eating when Richard stumbled upon the topic of gender roles with all the grace of a drunken soldier careening through a field of landmines.

“It’s in their DNA,” he said. “God created men and women different. That’s just how it is.”

“So you think women are put on earth to clean up after you?” I asked.

Richard speared a tomato with his fork. “I think everyone should do their job and not complain.”

Living in a “free country” does not protect American women from being talked over, underestimated, and disregarded. Four out of 10 American women have been discriminated against at work because of their gender. One in three American women will be stalked, raped, or assaulted. Sexism had dug its claws into my life well before I had the vocabulary to name it. I began picking up after my brothers in elementary school. By high school, I was folding their underwear, scrubbing their toilet, and carrying their dishes to the sink to wash after meals. I will never understand why my time and energy was viewed as disposable, but my brothers’ wasn’t.

After that lunch with Richard, I reacted differently than he had towards me the day I told him I would never believe in the Bible. Deeply hurt, I was unable to see past the rhetoric he had espoused. At his next lesson, I told him that I would still teach him the violin, but we would no longer spend time together as friends. He hung his head, then shuffled slowly to his car.

People’s words and their character

“All lives matter. Her body, her choice. Choose life.” Taken at face value, these words are immutable truths. What begins as a reaction to injustice becomes a slogan. These slogans and chants, so necessary to mobilising people and elevating marginalised voices, pull us into their orbit. They grow to encompass a movement, attracting other slogans like paperclips to a magnet. The movement adheres itself to a political party. The party becomes an identity for supporters, even though the average American has neither the time nor resources to become an expert on the nuances of public policy. Instead, we scream slogans across the street or share video clips to our own self-constructed echo chambers. If you believe Black Lives Matter, you must want to abolish the police. If you didn’t vote for Hillary, you hate women. Even when our intentions are noble, we stop listening to any voice that doesn’t mirror our own. Like spilled red and blue ink, the opposing parties grow larger, separated only by the election on which the future of America teeters.

It took months for my hurt feelings to fade enough for me to see through Richard’s rhetoric to the person underneath: a man who took over the housework while his wife studied for her nursing degree. A man who married young and worked to support his wife while she finished high school, despite his own lack of education. A man who had been married for 50 years, yet responded with compassion and acceptance when I told him my four-year marriage had ended. Richard had once relayed to me a conversation in which a man in his forties had lamented his lack of a wife.

“I just can’t find a woman willing to submit to me,” the man had told Richard.

“Submit? Well, that’s not how any marriage I know works,” Richard had snorted.

I learned to pay attention to Richard’s behaviour rather than the slogans he repeated. I had heard racist jokes and comments from liberal friends, only to watch them flood their social media with Black Lives Matter slogans once the movement rose to prominence. Growing up, the most judgemental people I knew always seemed to be devout church-goers. Richard’s actions paint a consistent picture of who he is as a person: kind, accepting, and empathetic.

Richard and Meghan’s dog, Wilbur, who loves to snuggle with Richard [Photo courtesy of Meghan Beaudry]

Richard and Meghan’s dog, Wilbur, who loves to snuggle with Richard [Photo courtesy of Meghan Beaudry]Richard never said another derogatory word about women. He became the first man I had ever met who, when confronted with his own misogyny, cared enough about me to change.

It is not easy to see past someone’s words to their true character. On the campaign trail, Donald Trump spouted promises. Walls to keep America safe. Lower taxes. The return of jobs to our country. Words have the power to wound, but also to uplift and spark hope. Some words, especially when they are words we want to hear, even have the power to veil the speaker’s true character. I began to see why so many Americans were hoodwinked by him.

Curiosity, respect and empathy

My conversation with Richard about gender roles set a precedent. We began to talk frequently and openly about our political beliefs. After some experimentation, we developed a tacit set of rules: Approach conversations with genuine curiosity about the other person’s perspective. Treat each other with respect and empathy. This empathy stems from an understanding that vastly different life experiences, many of them painful, have shaped our beliefs.

One of Richard’s most deeply held beliefs is that abortion is wrong. According to Gallup’s Values and Beliefs Poll, 46 percent of Americans are anti-abortion rights and 48 percent are pro-abortion rights, with 6 percent undecided. The difficulty in discussing abortion stems from who each camp views as the victim. When anti-abortion rights advocates talk about abortion, they talk about the babies. When pro-abortion rights people talk about abortion, they talk about the women. As a feminist, I can’t imagine being forced to carry a child I didn’t choose.

Richard and his wife raised just one child – a son who never had his own children, who lives 10 hours away and has his own life and health issues. Richard spends Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter with me at my parents’ house. Richard’s wife, Beverly, suffered miscarriage after miscarriage before giving birth to their only son. One of their children that didn’t survive is buried in a cemetery without a headstone because Richard and Beverly had been too poor to afford one. To come home to a house full of light, laughter, and grandchildren is Richard’s greatest desire. As I dropped him off after a family dinner one night, I watched Richard slowly shuffle up his driveway. Then I pulled away from the dark empty house. It suddenly clicked why Richard talks about “the babies”. It was never out of hatred for women.

The shape of our wounds

I have accepted that Richard and I will never be on the same page ideologically. Our friendship and ability to discuss divisive topics hinges not on our differences, but on our similar approach to life. We both believe in treating others with respect. We both harbour a magnetic curiosity towards those who are different than us. I will always be a liberal. But I have learned it is not just liberals who dream of a better America. From my friendship with Richard, I have learned that Americans’ ideas on how to improve our country often take the shape of their wounds.

Telling stories from the past is either the privilege or burden of the old. Richard revels in this role, peppering his stories with advice like “don’t buy no strawberries but Driscoll’s.” “Never tie two cats’ tails together and hang them over a clothesline,” he warned me once quite sincerely. But I always enjoy his stories and advice the most when Richard talks about the Great Depression and World War II.

“The government found out they were spying on us and rounded them up,” he said once about America’s Japanese internment camps.

Richard’s voice hit me like a shovel to the chest. His matter-of-fact tone implied that this was something everyone knew, like the events of Pearl Harbor or the reason for the American Revolution. We like to believe we are free in America. That we are different from countries like North Korea or Russia, who brainwash their citizens with a steady diet of pro-government propaganda. Richard’s statement summed up American propaganda in one phrase.

“That’s not true, Richard. They were Americans, too,” I said.

Two years later, I would learn about the Tulsa race massacre for the first time. In school, racism had been portrayed as an evil that Americans had long since vanquished. Video footage of police murdering Black people has long since eviscerated this lie. Since Richard’s statement, I’ve often wondered who I would be if I had no access to reputable news. What would I believe if I grew up under different circumstances?

My focus on Richard’s actions rather than his rhetoric was most tested the few times he used racially insensitive language.

Racism isn’t a personality quirk. It isn’t a vestige from a quaint antebellum past, like one-room schoolhouses or horse-drawn carriages. Racism is trauma that lasts for generations. Racism is lost lives and ruined futures.

I’m a liberal. A feminist. A believer that science is real, Black Lives Matter, and love is love. But perhaps the piece of my identity most deeply rooted in my heart is teacher. For me, that has always been the identity that makes allyship possible.

I speak up. “Richard, we don’t say that any more. It’s ‘people of colour’ now.”

Richard never argues. “OK,” he always agrees.

Access to the news

“Where do you get your news?” I asked recently. No TV hangs in Richard’s living room. His home is a museum dedicated to his late wife; Beverly’s floral curtains and silk floral arrangements remain untouched by Wi-Fi or cable. No copy of the New York Times lands on his doorstep each Sunday. An old radio sits on his kitchen table.

“Mostly from what people say,” he shrugged. “And sometimes the radio.”

My heart sank. From the day we met, Richard spoke openly about his lack of education and his humble background. As a teacher, I recognised his fierce commitment to learn shining through the unvarnished front he presented. As an adult, Richard had taken flying lessons and painting lessons. He approaches the Bible the way a scholar of history would. He pores over gardening manuals and maintains an encyclopedic knowledge of the flowers and trees in his garden.

I had convinced him to trade in his flip phone with T9 texting – “it’s not a phone, Richard, it’s an ancient artefact,” – for a touchscreen Android. He has since become a connoisseur of selfies and of video clips of the American flag in his garden waving in the wind. Richard strikes me as an independent thinker – someone who isn’t fooled by con men or false political promises. But from our conversation, a clearer picture emerged: an intelligent man, but without the resources to access the news or discern its accuracy.

I scribbled a note to myself to print and bring some news articles to our next meeting. The New York Times. The Atlantic. Maybe a Christian news source with solid reporting. No op-eds – just straight news so Richard could form his own opinions.

Richard told me he had listened to the first debate between Joe Biden and Donald Trump on the radio.

“I couldn’t sleep it bothered me so much,” he said. “(Trump) denied what Joe told him he’d said. But everyone very well knows what Trump said. People have ears.”

“Thou shalt not bear false witness. It says that clearly in the Bible,” Richard added with a frown.

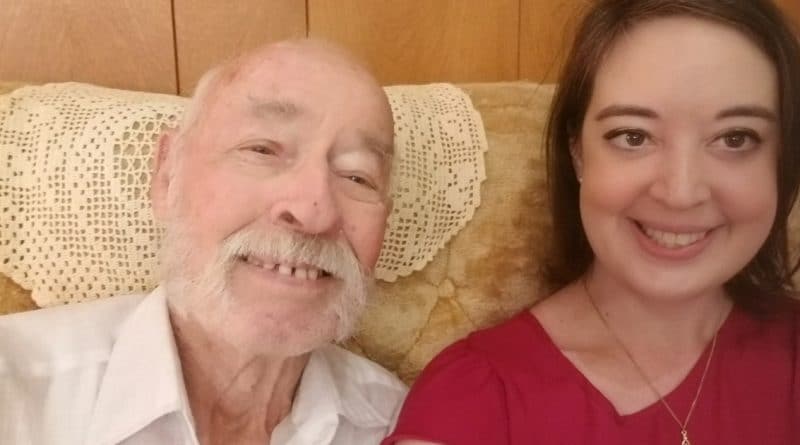

Richard and Meghan take a selfie after playing a concert at a nursing home [Photo courtesy of Meghan Beaudry]

Richard and Meghan take a selfie after playing a concert at a nursing home [Photo courtesy of Meghan Beaudry]Past the slogans and rhetoric

As Richard has aged, the lines in our relationship have blurred from teacher to friend to caregiver. I want him to know he always has a place at my Thanksgiving table. That I’ll be there in the hospital when he wakes up from his heart procedures. That my family will keep filling his fridge so he can quarantine safely.

“You don’t have to tell me,” I said. “And if you do, we’ll still be friends no matter what. Who do you think you’ll vote for this election?”

“I believe in what our forefathers said in the Declaration of Independence. But as culture has changed, my thoughts have changed. Being Christian doesn’t mean you have to be Democrat or Republican. It means voting what you believe in,” Richard said.

Our friendship has taught me to see past slogans and rhetoric to the person underneath. That actions convey character in a way that words can’t. But in this respect, perhaps Richard is miles ahead of me.

“I think Trump has accomplished some things,” he said with his characteristic respect for our country’s leaders. “But those things might have been accomplished anyway through other people. He seems to really support all his friends and companies. Not the little man.”

“You know, I think I might vote for Joe,” he added after a pause. Outside Richard’s window, his American flag waved in the wind.