The New Wave of Fashion Criticism | Intelligence, BoF Professional

NEW YORK, United States — For most of fashion’s front row, watching shows through smartphone screens this season requires a bit of adjustment. But for an increasingly influential class of online critics, it’s already second nature.

“Reviewing collections online? No problem, easy peasy,” said Luke Meagher, a 23-year-old fashion commentator who started reviewing collections online in 2017 while still a college student, and has only attended a few shows in person.

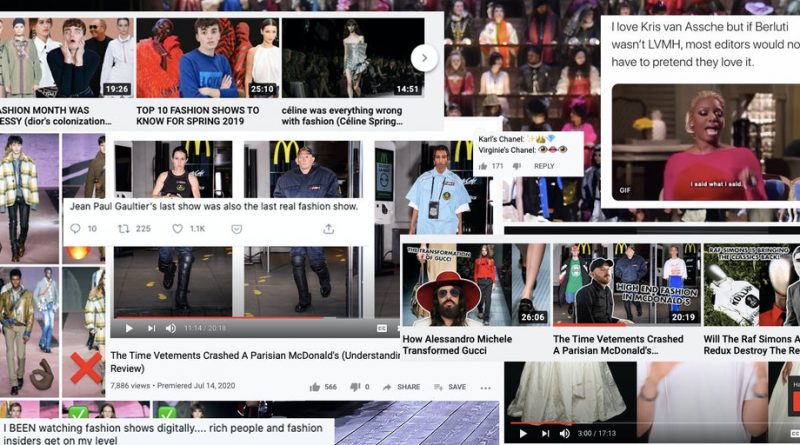

Meagher has over 440,000 subscribers on YouTube as “HauteLeMode,” where he mixes critiques of the latest high-fashion collections with coverage of red carpets and other internet-friendly fashion moments. His videos jump back and forth between fashion history lessons, pop culture references and Youtube-ready zingers, which he relays in a newscaster’s rhythmic timbre. He also has a meme account on Instagram, is active on Twitter and has a podcast.

In a recent video reviewing the Autumn/Winter 2020 Couture collections, Meagher knocked Maria Grazia Chiuri’s Dior, zooming in on an image of one metallic embroidered gown and asking, “Does it look better up close? Maybe to those with the most scary of the coronavirus symptoms: the lack of taste.”

Meagher commenters ate it up. “He doesn’t suck up to designers,” wrote another viewer. “This is why I trust his opinions.”

In a fashion media landscape where advertisers wield enormous influence and cookie-cutter celebrity news dominates web traffic, people are flocking to accounts like Meagher’s that wear their lack of access like a badge of honour. Even as magazines cut staff, a new form of fashion criticism is thriving online in the form of memes, Tweets, Instagram story slideshows, lengthy videos and TikTok clips.

For the most part, these aren’t Diet Prada wannabes. Education and discourse is the goal, not cancellation, and often the tone is lighthearted.

And though online communities are as old as the internet – fashion fans once congregated on Tumblr, independent message boards and comments sections – their popularity has escalated as brands share more information online about their collections than ever before.

“Articles don’t necessarily reach [young people], just because it’s not in a consumable format for them,” said photographer Iolo Lewis Edwards, founder of the private Facebook group High Fashion Talk, where young fashion professionals, designers and students debate, for example, the merits of Kim Jones’ appointment at Fendi. “There’s a massive thirst for this sort of analytical content,” he said.

Just as the purpose of fashion shows are being called into question now, so too is the role of the runway review, a practice popularised by critics like Suzy Menkes, Cathy Horyn, Robin Givhan and Tim Blanks. They inspire today’s young critics, who lament that their approach is drowned out in the endless feed of online content.

If fashion criticism is going to survive a more fragmented, digital future, it needs to adapt, and there is a wave of young people trying new things on new platforms, without waiting for the permission from the establishment.

“Good criticism comes out of knowledge and context, and it takes awhile to build up the knowledge and context to speak not just thoughtfully but also confidently about a collection,” said Givhan, senior critic-at-large at The Washington Post. She said emerging critics appear to be “putting in the work” to develop their critical voices.

What new critics lack in experience or institutional knowledge, they make up for in presentation style, engaging a fickle audience that grew up scrolling Instagram rather than paging through fashion magazines.

The New Fashion Lexicon

Pierre Alexandre M’Pelé, known as Pam Boy online, started writing critiques on Instagram and Twitter while studying fashion journalism at Central Saint Martins. He first gained a following more than two years ago for posting reviews in Instagram Stories, delivering a verdict on each look with a single emoji. The knife emoji, for example, denotes “sharp tailoring.”

“It was about finding a language that would be instantly recognisable and understood by the people following me,” he said. M’Pelé now has more than 44,000 followers on Instagram and Twitter, where he shares quips, criticism and commentary on the industry. While he still does the occasional emoji review, he feels he has “exhausted” the concept. He was hired as senior editor by Katie Grand’s Love magazine this year, and then followed her to her new venture The Perfect Magazine.

It was about finding a language that would be instantly recognisable and understood by the people following me.

Not all of these new critical voices put themselves in the front of the camera like Meagher. And even when they do, they don’t always look like traditional fashion influencers (decked out in the latest collections) or the stereotypical magazine assistant (white, wealthy and connected).

“I make it a thing to always wear plain black t-shirts and every video because then it’s never about what I’m wearing, about what I’m saying,” said Ayo Ojo, a London-based Central Saint Martins fashion journalism student who started his Youtube channel, The Fashion Archive, as a teenager. Ojo is also on Twitter and Instagram, has a private Discord group on fashion with 1,700 members, hosts a podcast and is launching a print magazine.

On Youtube, Ojo produces carefully researched videos about single topics like the rise of Telfar, as well as collection reviews, in a serious, even-keeled tone. His most popular video to date was a two-hour dissection of all of Vetements collections posted a year ago. It took him a month to make, but was removed for copyright violations in March.

Ojo also regularly hosts live videos after industry news breaks, including a marathon 10-hour session after Jones’ appointment to Fendi, where anyone can ask a question or share the screen. The conversations extend beyond fashion too. A June livestream titled, “Ask Me Anything About Racism,” touched on everything from Ojo’s personal experiences as a Nigerian in Britain to how brands should respond to the Black Lives Matter movement.

While these niche online fashion communities are willing – sometimes gleefully – to skewer fashion’s sacred cows, they are busy creating a new consensus of their own, one that’s more in line with their mostly young, progressive followers.

Chiuri is a frequent target (she is seen as guilty of cultural appropriation), and Virgil Abloh is controversial for allegedly copying other designers’ work. Martin Margiela is unimpeachable, and other favourites include Jones, Rick Owens, Yohji Yamamoto, Comme des Garçons, Mowalola Ogunlesi and Peter Do. Jacquemus also gets plenty of attention, though he has lost some fans after repeatedly going viral last year.

The criticism isn’t just reserved for garment construction: designers and brands are often evaluated by their social justice efforts and sustainability initiatives.

Together they are stitching together opinions that are forming the tastes of a new generation, even if few can afford to buy from the designers they carefully analyse.

“Once, when you were young and into fashion, it was often the way that you had to create your own world, and that is still the power of what these kids do,” said BoF’s Editor-at-Large and chief critic Tim Blanks.

Questioning the Establishment

Online fashion communities police each other for inaccuracies and missed reference points. But the worst sin is being in the pocket of the brands.

“You never know if [magazines or other fashion publications] are just saying something because they’re getting paid to do it,” said Edwards, founder of the High Fashion Talk Facebook group, verbalising a widespread desire for authentic opinions.

“I was trying to write what I wanted to read and that I couldn’t find anywhere else, or in very few places,” said M’Pelé about his start in criticism. “I call it the love triangle — you have the fashion companies, you have the media and you have the PRs.”

Few online critics have direct contact with the labels they discuss and, except for a desire to see show notes, many say they don’t want or expect their attention.

Palestine-based international law student Marah Abdelal, also known as @vogueheroine on Twitter where she has more than 12,000 followers, is part of the “High Fashion” Twitter community, a group whose members debate about everything from the role of the Black Lives Matter movement in fashion to whether fashion is too dominated by consumerism as opposed to artistic motivations. She prefers Twitter as her outlet because she said it is less rife with sponsored content than Instagram.

I was trying to write what I wanted to read and that I couldn’t find anywhere else, or in very few places.

Horyn, critic-at-large for The Cut at New York Magazine, said the new wave of critics is smart to protect their position as industry outsiders. “I hope that they value that above everything else… and then get really good at saying what they want,” she said.

Balancing the Needs of the Audience

Many of the digital critics actually prefer to avoid spending time on negative reviews. When they pan a show, it’s often via more ephemeral formats, like a disappearing Instagram story or a YouTube livestream.

While M’Pelé realised early on that followers loved to see him attack Kering or LVMH brands, “it’s usually the reviews that are positive but critical that help me build my following and get me more traction and engagement on my Instagram,” he said.

Similarly, Ojo only has time to review one or two shows a season due to the amount of research and production involved and he’d rather spend the time on a collection or designer that interests him, like Demna Gvasalia’s collections at Balenciaga.

Ojo is frustrated not only by the influence of advertisers in the media, but also the pressure to chase traffic online by covering the biggest brands. In a recent video titled “The Death Of Fashion Magazines (RANT),” he said this pressure results in “watered down” content.

“You have to look past what everyone looks at,” Ojo said, citing a video he made on Italian designer Isabel Benenato as an example, which only generated less than 4,000 views. (Ojo’s videos on the likes of Gucci and Balenciaga typically get more than 20,000 views.)

What Comes Next?

With the unprecedented amount of digital content brands are churning out now and for the foreseeable future, fashion’s online critics have more access than ever before, spurring more newcomers to pick up the practice.

“People message me saying that I’ve inspired them to start their own Instagram account, dedicated to fashion reviewing,” said M’Pelé. And while he is supportive of more voices, he said there is a lot more “noise” online, creating a gap even among the youngest generation of critics.

Meanwhile, the industry is fragmenting and consolidating, and many emerging and independent designers businesses will not survive the pandemic.

“With the industry less and less durable, what does the commentary become?” asked Blanks. He sees fashion criticism evolving into social commentary, reflecting a new generation’s activist impulses.

As critics like M’Pelé continue to develop their voices, they also see larger ambitions.

“I feel like I’ve reached a space that forces me to transition into…a place of greater influence to help drive change within the power structure of the industry,” M’Pelé said. “Fashion doesn’t evolve in a vacuum and it’s not the bubble that it used to be. We have to connect it socially, economically, culturally to what’s happening in the world.”

Related Articles:

The BoF Podcast: The Fate of the Physical Runway Show