The never-ending bulls**t over Pike River

Rebecca Macfie

Rebecca Macfie is a leading investigative journalist, and the author of Tragedy at Pike River Mine (Awa Press, 2013), and Helen Kelly: Her Life (Awa Press, 2021), which has been longlisted for the best book of non-fiction at the 2022 Ockham New Zealand national book awards.

ReadingRoom

Rebecca Macfie on the ninth reprint – ninth! – of her classic book about the tragedy at Pike River Mine

There’s no good time to tell a story without end. There will always be things missing, events that unfold just as the presses start to roll, some angle that would have come into sharper relief if only the print date had been pushed out another year, another five, another ten.

But you draw a line through time and say: “This is it, in all of its inevitable incompleteness; this is the story I was able to wrap my arms around, the best I can manage for now.”

My publisher Mary Varnham and I knew this when Tragedy at Pike River Mine: How and Why 29 Men Died came out at the end of 2013. By then it was three years since the mine blew up, and the book told a story that I thought needed to be reported sooner rather than later: a story of hubris and incompetence and corporate fantasy. It was about the tap-root of catastrophe, about made-up numbers and grand promises and men who thought they knew better than all the rest. It was a story that I hoped New Zealanders would read and understand just how egregious was this company’s failure, and how blind and ignorant its leaders.

I especially wanted company directors and top bosses to read it. Many had tut-tutted in the years after Pike, and said how dreadful it was and how their company might have its faults but it was nothing like this outfit, whose casual disregard for catastrophic risk had been laid bare by the Pike River royal commission. It worried me that the Pike company, by dint of killing an extraordinary number of workers, would be framed as extraordinarily terrible, when in many ways it was just an ordinarily below-average company. It thought if it could just fix this week’s problems then next week things would be going brilliantly. It ignored workers when they spoke up. It told white lies to please the markets. It spun bullshit PR about how capable and clever and innovative it was – a thoroughly modern mining company – and it believed that bullshit to be true. It had the ordinary flaws of other failed companies that I’d reported on over the years, but instead of simply going broke – as it eventually would have done – it blew up and killed 29 people and then went broke.

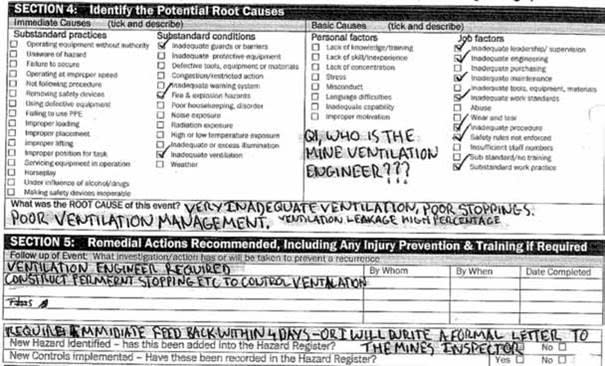

Tragedy at Pike River Mine was the story as far as I was able to understand it at that time: Pike’s slow start, fateful decisions steam-rolled past an enfeebled regulator, machines that didn’t work, a ventilation shaft that collapsed and got patched up; red flags ignored by incurious directors, coal production that was endlessly delayed yet always just around the corner. That slow start built into a sprint to catastrophe. Methane spiked in mine roadways and hissed through underground pipes. Workers wrote angry incident forms that ended up in the bin. A brand new underground fan let off sparks, and a brand new mining machine couldn’t get the coal out. The company’s leaders decided that a good response to these difficulties was to pay the workers a big fat bonus if they got the mine into production by a target date.

It was the story of disaster that stalked every day, of looming failure hidden away by Pike’s incessant spin and plain lies and by the stupendous rugged beauty of the Paparoa mountains.

At some point during the late stages of editing Mary suggested we add a timeline to the book to help readers follow the train of events. It would be a handy reference tool, too. Eg, “2005: Peter Whittall is recruited as mine manager, responsible for developing the mine”; “2007: Initial public offering raises $85 million…by 2009 production will reach a million tonnes of coal a year”; “2008: Ten gas ignitions terrify workers”; “2010: Pike’s first shipment of coal, 20,000 tonnes, leaves Lyttelton…Investors are told the mine will soon be producing a million tonnes of coal a year”. [NB: By the time Pike blew up on November 19, 2010, it had exported just 42,000 tonnes of coal. It wasn’t even a coal mine yet, just a mine development project.]

Critical new phases of the story were still to come. In 2014, the year after the book was published, Peter Whittall was to defend 12 health and safety charges in a court hearing that would hopefully deliver some accountability and answers for the families of the dead. And more would be learned about what happened underground – and perhaps some bodies would be recovered – when Pike’s new owner, Solid Energy, completed its government-funded project to re-enter the 2.3 km access tunnel, the ‘drift’. Perhaps naively, I though both of these events would proceed and reach some kind of conclusion. Then we would produce a new edition of the book, with a tidy final chapter.

But no. At the end of 2013, Peter Whittall walked away from his charges after $3.41 million was paid to the families in a cynical deal found later by the Supreme Court to have been unlawful. At the end of 2014 Solid Energy bailed out of the drift re-entry project. At the end of 2016 Pike families occupied the mine access road to stop the portal from being sealed with the bodies of their sons and husbands and brothers inside. At the end of 2017 a new government promised to try again to re-open the drift and gather forensic evidence and, perhaps, bodies. The police, having ruled out criminal prosecution in 2013, reopened the file, put together a dedicated team of detectives and started a long and detailed investigation that could yet result in manslaughter charges. At the end of 2021, bodies were found – not in the drift, which had been successfully re-entered and examined, but by cameras lowered down police boreholes into far corners of the mine. There will be more boreholes yet, and more bodies seen.

The ever-growing timeline at the back of the book has allowed us to capture these unfolding strands of the endless story in each of eight reprints, sometimes two a year. Now the ninth has appeared. By now there is so much new information, Awa Press has called it a new edition.

As for those company directors and top bosses who I wanted to read the story and recognise themselves in it – I hear sometimes that they have taken note, and that they pass the book around the boardroom and require their executives to read it, that they discuss the lessons of Pike and consider their own susceptibility to hubris and bullshit. And yet, and yet… alarming numbers of New Zealand workers continue to die on the job every year, health and safety is still trivialised and seen as a cost burden, and those who ultimately hold the power to save workers’ lives – those at the top table – continue to avoid any personal accountability. New Zealand farms, forests, roads and construction sites are still killing fields. Enforcement is still scarce. Workers lives are still cheap.

Tragedy at Pike River Mine: Updated Edition by Rebecca Macfie (Awa Press, $45) – winner of the Best First Book of Non-fiction at the 2014 New Zealand book awards; the Bert Roth Award for Labour History; and the Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy Media Award – is available in bookstores nationwide.

Tomorrow in ReadingRoom: A tribute to the great New Zealand literary translator Geraldine Harcourt, who created an “unfathomable kind of magic”