The Gifts of Gary Blackman

Ideasroom

Thomas McLean has lived in Dunedin for 16 years, during which time he has had the chance to enjoy the city’s artistic riches through the photography of Gary Blackman. Here he discusses some of the images that have had the biggest impact on him.

I have a very clear memory of the first Aotearoa New Zealand photograph that made a deep impression on me. It was early November 2004; I had travelled to Dunedin from the United States for a job interview. Fairly certain that I would not get the job, and not knowing when I might return to the southern hemisphere, I added a week of sightseeing to my itinerary.

Wandering in the galleries of Te Papa, I was immediately drawn to a black and white image of school children standing outdoors, gazing at something in the distance. What was it about the image? Though the children seemed, at first glance, to be in a jumble, in fact there was a clear compositional quality to the picture: one could easily draw a diagonal line along the faces from the bottom left corner to the top right.

The neat dress and trim haircuts suggested the simplicity of an earlier time: 1950s New Zealand. And there was something about the mix of expressions and attitudes: some showing concern, others conveying the pleasure of an unexpected diversion; some in shadow, others in full light. And then, in a composition that is all about heads and shoulders, one straight arm breaks up the flow of diagonals and fills the otherwise empty upper right corner, looking like Michelangelo’s hand of God come to North East Valley.

The photograph, titled Children Watching a Gorse Fire, was taken in 1952 by Gary Blackman. The fact that the photograph was created in Dunedin, my prospective future home, certainly caught my attention. It was somehow important to know that striking works of art could be set and made there. But the image stayed with me because it was just a great picture.

Years later, at a Dunedin Public Art Gallery event, I spoke to Gary and his wife Margery, herself an extraordinary textile artist, and I told them of the impact his photograph had on me. He shrugged it off with a friendly modesty that I understand is typical of him.

Children Watching a Gorse Fire was one of Gary Blackman’s earliest photographic works. Over the five succeeding decades, he would use the medium to create a remarkable visual record of New Zealand. He’s perhaps best known for his no-nonsense photographs of buildings and architectural elements. Indeed, his 1968 book Victorian City of New Zealand, a collaboration with Ted McCoy, is a keystone work in the recognition of Dunedin’s built heritage.

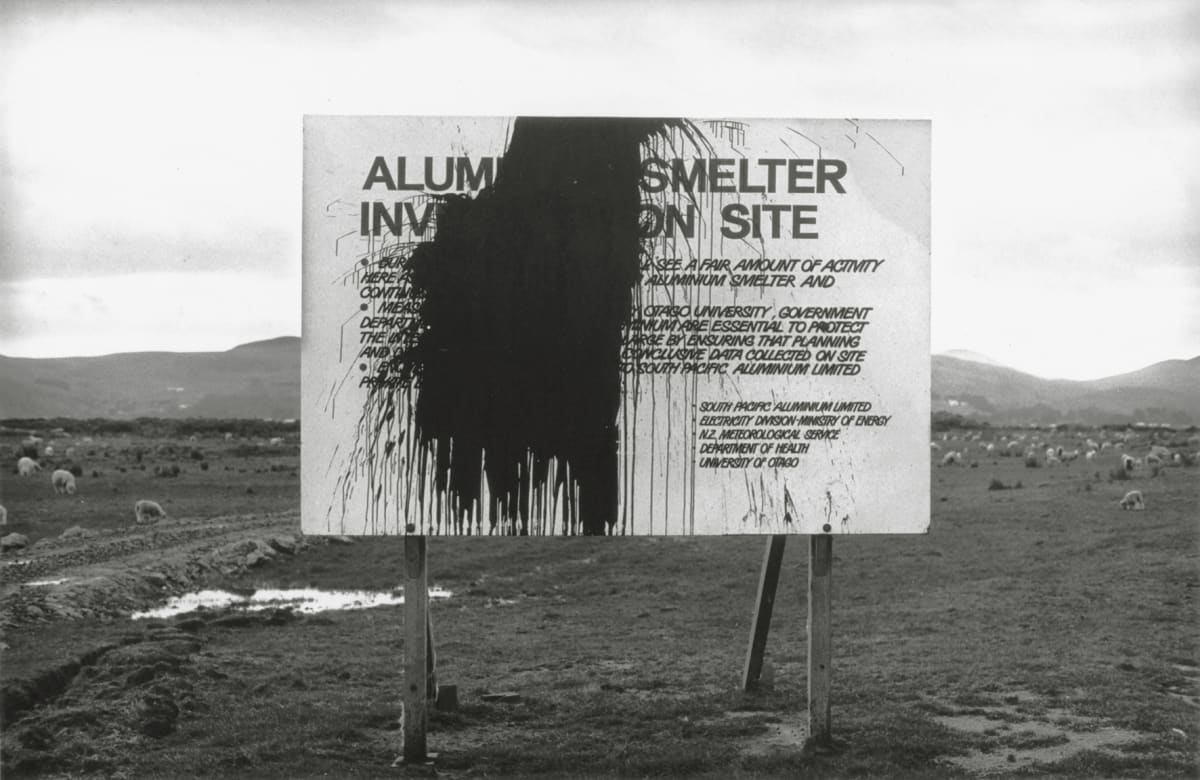

But I also admire his more idiosyncratic photographs. Penguin, a 1975 image of an inflatable penguin floating alone in a Blenheim pool, manages to be both playful and melancholy. It graced the cover of the catalogue for his 2003 Dunedin Public Art Gallery exhibition ‘Survey’. His memorable 1980 photograph of an Aramoana smelter sign splashed in paint features in the exhibition ‘Ralph Hotere: Ātete (to resist)’, currently in Christchurch (the splasher was apparently Hotere himself, who later called the sign “probably the best painting I’ve done in 30 years”).

Gary created these images in his spare time. From 1954 to 1995, apart from three years in Edinburgh, he had a long career teaching pharmacology at the University of Otago. While he may not have the name recognition of New Zealand photographers like Anne Noble or Laurence Aberhart, his images deserve a place in any history of New Zealand photography.

Start your day with

a curation of our top

stories in your inbox

Start your day with a curation of

our top stories in your inbox

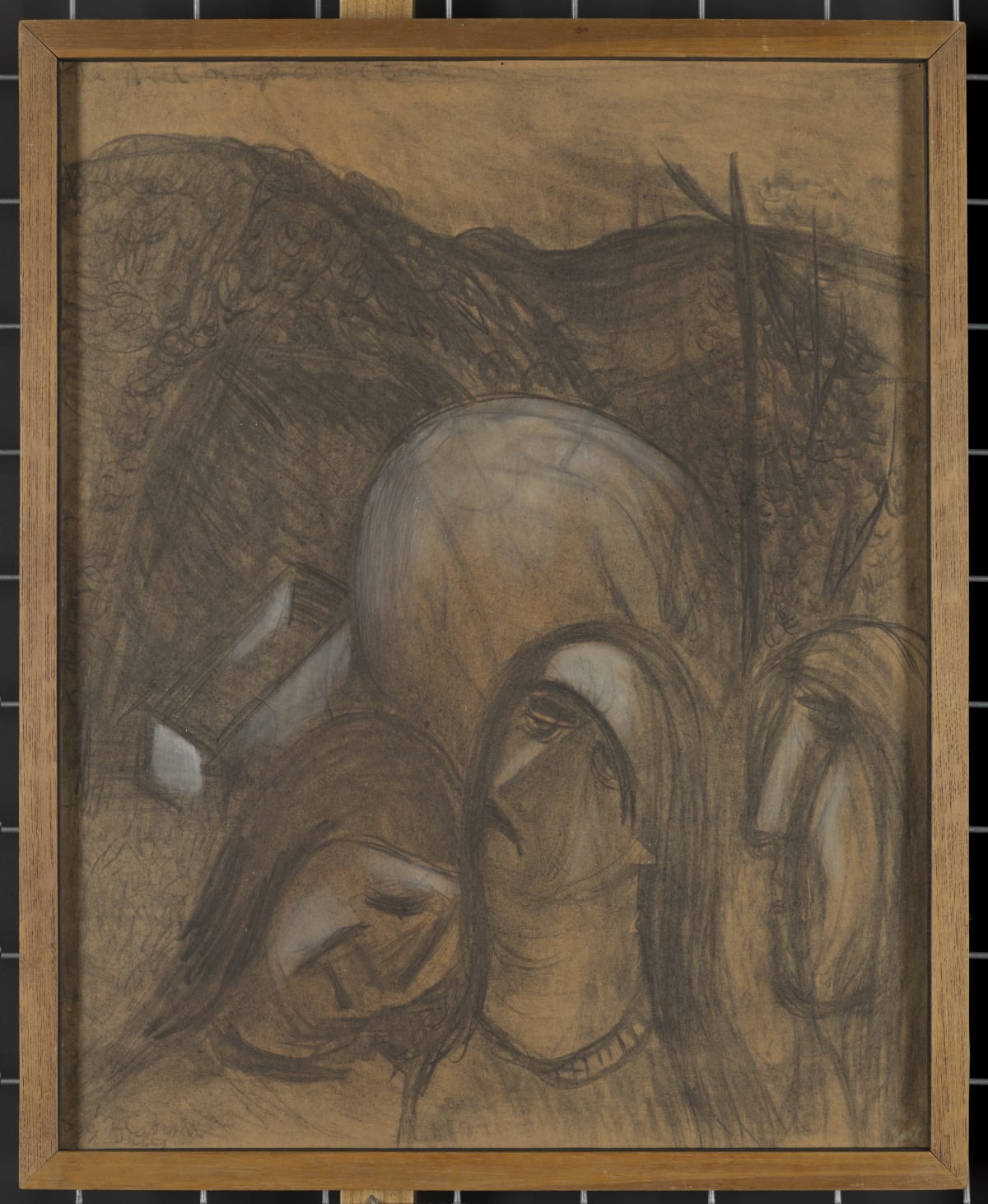

I thought of these images and their maker a few days ago, during a visit to the Hocken Library’s excellent exhibition, ‘Colin McCahon: A Constant Flow of Light’. I was pleased to see that several works had been added since the last time I visited. These included a charcoal drawing from 1947, The Three Marys at the Tomb. In this mournful image, the three women are in the foreground, before the tomb of Christ, where the stone has been rolled away and the coffin stands empty.

Though the drawing of the women suggests the influence of the French artist Georges Rouault, other elements show McCahon refining his own style. Most commentators agree that he has set this climactic New Testament scene before the hills of Nelson. In the circles and half circles, almost like fish scales or feathers, that fill in those hills, is there a suggestion of the angel who will tell the women that Christ is risen? Perhaps there is also a hint of the rounded Cubist forms that would later appear in McCahon’s kauri tree paintings.

Beside the drawing, the Hocken has placed a framed letter from the donor, none other than Gary Blackman, explaining the drawing’s provenance. Gary purchased the drawing from a Dunedin exhibition in 1948, when he just 18 years old—not much older than those children watching the gorse fire—and it remains in the frame in which it was originally shown. It is more evidence that Gary has a remarkably good eye.

And a remarkably generous spirit. In the 16 years I’ve lived in Dunedin, I’ve often heard about (and occasionally seen) the many remarkable collections of art that are preserved in private homes. It’s nice to live with beautiful objects; it’s even nicer when, after a period of living with such objects, their owner decides to share them with the wider community. And best of all, when they share it with their own community.

I’m sure that many art galleries in Australia and New Zealand would have been more than pleased to receive such a donation. I’m glad that Gary and Margery Blackman decided to keep the work in Dunedin. And I feel fortunate to have first glimpsed the artistic riches of this city through Gary’s photography.

Thomas McLean is author of The Other East and Nineteenth-Century British Literature: Imagining Poland and the Russian Empire (Palgrave 2012) and co-editor with Ruth Knezevich of Jane Porter’s 1803 novel Thaddeus of Warsaw (Edinburgh, 2019). He has written on art, literature, and migration for The Migrationist, The Conversation UK, and the Los Angeles Review of Books.