Testing Businesses’ Commitment to Climate Action

Comment

Beware any company or industry group that puts naive faith in modelling as an excuse for avoiding constructive engagement, writes Rod Oram

Are businesses and politicians committed to tackling the climate crisis?

There’s a perfect test to tell. If they obsess about economic modelling they don’t understand the enormity of the crisis, the complexity of our responses, or the fatal flaws of modelling.

They’re using modelling as a classic distraction from the fundamental issue. Quite simply, they don’t want to take responsibility for their emissions and to play their role in reducing them.

Sure enough, angst about modelling is the only response we’ve heard from some leading business organisations, and National and ACT, since the Climate Change Commission released six weeks ago its draft carbon budgets and emission reduction pathways for the next 15 years.

Yet the decisions we make this year about those will fundamentally determine whether we succeed or fail in reaching our goal of net zero emission by 2050 and thus stave off the worst of the climate crisis. They will also determine whether we benefit from a modern, high tech, sustainable economy or are burdened by a 20th century, polluting industrial and consumer dinosaur.

In mid-February a coalition of business organisations wrote to the Commission asking it to make public all its modelling methodologies and work. The group included Business NZ, the NZ Initiative, Federated Farmers, DairyNZ, the Meat Industry Association, the Motor Industry Association and Straterra, the mining industry association.

The Commission had included extensive coverage of its modelling and how it had used it in its draft report released February 1. To that, it has added almost all of its modelling to its website, which anyone can download. These models have also been peer-reviewed at home and abroad. Once it has resolved some intellectual property issues with contractors it will release the last few components around mid-year. But even if those include some elements for critics to seize on, they won’t significantly change the results of the modelling.

As the Commission explained in its report: “All models are necessarily a simplification of a more complex system and are not intended to represent all aspects in detail. Therefore, it is not possible or appropriate to solely rely on models to guide our advice. Modelling is therefore an important part of our analysis, but it is only one component. We have complemented our modelling with other quantitative and qualitative analysis to help us reach our recommendations.”

The Commission used mainstream Computable General Equilibrium modelling. Essentially, this factors in a big change in an economy, such as a rapid wind down of oil and gas exploration, and calculates the knock on effects through the economy. This can size the “hole” in the economy but even the most sophisticated versions can’t adequately assess how innovation, new investment, policy responses, behaviour change and myriad other factors cause new and different activity to flourish.

A classic example of such skewed models and unrealistic outcomes was the modelling NZIER did for the Petroleum Exploration and Production Association of NZ after the government stopped issuing new exploration licences outside Taranaki. NZIER declared that the ban would “reduce real gross GDP by between $15 billion (3 percent) and $38 bn (7.4 percent). The medium scenario is a reduction of $28 bn (5.4 percent).”

I wrote about the inadequacies NZIER’s work – for example it didn’t use its NZ Green environmental component in its modelling work – and the inadequacies of modelling generally in this February 2019 column.

A few months later in 2019, NZIER’s modelling, and modelling in general, became an issue once again. This time it was NZIER’s analysis for the government of the Zero Carbon Bill. Treasury commented on it at length in its Regulatory Impact Statement on the Bill in May. It’s worth quoting at length because National and some business leaders have cast doubt on the Commission’s work this year by citing this NZIER work from 2019.

“The economy-wide impacts of officials’ recommended 2050 target option were assessed as follows: The economy continues to grow but at a slower rate than expected for the current gazetted 2050 target. The New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER) finds that the recommended target option could slow economic growth by 0.07-0.18 percentage points compared to the current 2050 target, which is $5-12 billion per year over 2020-2050.

“Note that these results are highly sensitive to assumptions about the level of forestry sequestration (modelled as 19-23Mt). Modelled costs fall sharply under higher sequestration assumptions. Emissions prices rise from their current level. The two modelling studies undertaken project a wide range of emissions prices from $75–885 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (/tCO2-e) by 2050.

“The Productivity Commission notes that the range of emissions prices estimated as necessary in other developed countries to deliver on the Paris Agreement is $100-250/tCO2-e at 2050. Note these are emissions prices that would be faced across the whole of the economy, not necessarily by specific sectors, industries or NZ ETS [Emissions Trading Scheme] participants.

“It is critical to note that the impact magnitudes reported above do not consider some important factors that, if also quantified, would be expected to lessen the modelled challenge of the transition. Qualitative and empirical analysis has been undertaken on the impact of a changing climate on New Zealand’s economy, on the potential for stronger emissions targets to drive faster innovation and to reap wider co-benefits (eg, health or environmental outcomes). These cannot be fed into NZIER’s modelling within the time available and so the challenging impacts reported could well be overstated. An expert peer-reviewer has found NZIER’s results to be at the higher end of the plausible range of impact.”

In contrast to the measured view from Treasury, Business NZ’s submission on the Bill used intemperate language to attempt to undermine the whole strategy of our national transition to a low emissions economy.

“While we support this Bill, we nonetheless continue to be concerned about the heavy reliance on the modelling in both the setting of the targets and the mechanisms to achieve them. In our submission to the Ministry for the Environment (the ‘MFE’) we said:

We have no confidence in the modelling or its reliability for the purpose of decision making with respect to an emissions reduction target. We are concerned that the modelling undertaken by GLOBE-New Zealand, the Productivity Commission and MFE is being used as supporting, or justifying a target. The modelling provides a set of information that is highly assumption dependent and simply cannot, in any shape or form, be used as endorsing a particular course of action. Modelling, like the science, is informative but cannot be determinative.

“The two models on which MFE relies vary on the one hand between wishful thinking in terms of the uptake of new technology and a reliance on a ‘then magic happens’ approach to assumptions (such as the uptake of a methane vaccine and the assumption that all other jurisdictions are taking commensurate action), and truly alarming economic results on the other. The analysis by NZIER suggest that GDP will continue to grow but will be in the range of 10 percent to 22 percent less in 2050, compared with the current state of action on climate change.

“These are quite staggering in terms of trade-offs for uncertain (indeed only modelled) benefits and suggest caution.”

The Taxpayers Union also cited the NZIER’s estimate of the high cost to the economy in its submission on the Bill.: “In comparison to taking no further action on climate change, NZIER’s modelling ‘suggests that GDP will continue to grow but will be in the range of 10 per cent to 22 per cent less in 2050’.”

Despite experts’ verdicts on the plausibility of NZIER’s 2019 modelling, the National Party is still citing it. Leader Judith Collins, an avowed climate denier, said in February about the Commission’s draft recommendations: “I think they are the only people saying 1 per cent. Lots of people are saying other numbers.”

Soon after, National Party MPs Scott Simpson and Stuart Smith, its environment and climate change spokesmen respectively, challenged Rod Carr, chair of the Climate Change Commission, in a select committee hearing. They focused particularly on the Commission’s estimate of the cost to GDP of the transition to a zero emission economy by 2050. “Of course, you do understand that given that your assumption of less than 1 percent of GDP is a factor of five lower than NZIER’s work, that is creating some suspicion,” Smith told Carr.

The Commission’s estimates of the reduction in GDP was only 0.3 to 1 percent. This would be the cumulative loss over the entire period to 2050, meaning the economy would reach the same level of activity a mere 6-7 months later in 2050 than taking no action.

The Commission’s sharply lower relative cost to the current policy baseline, compared with NZIER’s earlier work, is in line with the work of similar climate bodies overseas. In all countries the marked reduction in costs in recent years reflects rapid innovation in clean technologies and other favourable factors. The Commission cited these examples in its draft recommendations:

- UK: GDP 3 percent higher relative to baseline, using macroeconomic model methodology similar to our Commission’s; or a net cost of less that 1 percent using a resource cost assessment.

- EU: GDP 1.3 percent lower to 2.2 percent higher, relative to baseline, using a suite of three different macroeconomic models.

- Energy Transitions Commission’s global analysis of hard-to-abate sectors: Net cost of 0.2 to 0.5 percent of projected global GDP.

Modelling is a useful additional tool for helping us to compare options for public policy and business strategy, and to make complex, long term decisions. Yet, National, ACT, the NZ Initiative and some of our main business organisations argue it should be a dominant tool.

They believe such models and market signals from the Emissions Trading Scheme will enable emitters to make better informed and economically more beneficial decisions out to 2050 than a bureaucrat “sitting at a desk making their best guess about the consequences of policy change,” in the words of one advocate of models and markets interviewed for this column.

Yes, ultimately the Cabinet will decide on carbon budgets, pathways and policies on information and analysis prepared by the Commission staff and civil servants; and Parliament will vote on them.

But the quality and ambition of those decisions, and the effectiveness of their outcomes, will be significantly determined by the quality of engagement in the process from as many well-informed participants in the economy as possible from companies large and small, to NGOs and other organisations, and consumers and households.

We’ll be able to judge the quality of that input from the submissions being made to the Commission by its deadline on March 28. But beware of any company, industry or business organisation that puts naive faith in modelling as an excuse for avoiding constructive engagement, as Business NZ did on the Zero Carbon Bill. Modelling is a fourth order issue.

The first order issue is for emitters to take responsibility for their contribution to the climate crisis.

Their second order issue is to make binding commitments to drastic emissions cuts as their contribution to us as a nation meeting our zero carbon goals, and to their interim goals along the way.

Their third order issue is to detail their strategies to do so, how they can help other emitters, and to identify for government what policies and help they need to do so. As a result of such input, for example, the UK has a well-developed and detailed industrial decarbonisation strategy.

New Zealand business needing guidance on constructive engagement with government need look no further than the Confederation of British Industry, which has been a strong and effective climate champion for well over a decade, despite still having a rump of members who are climate crisis deniers.

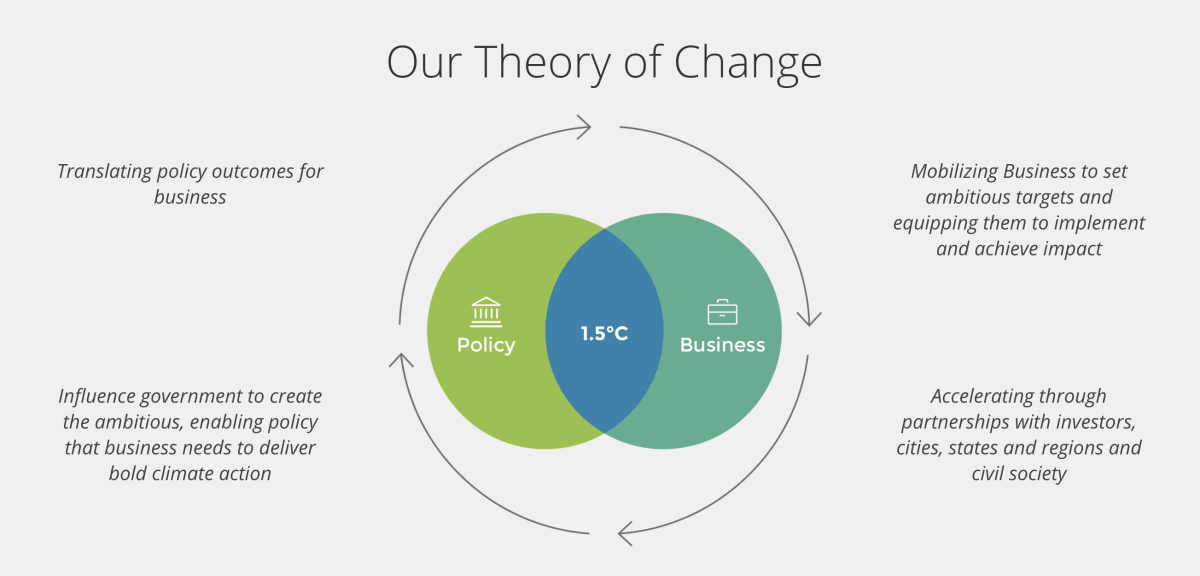

Likewise there are many business coalitions worldwide whose members have deep and binding commitments to climate action. One example is We Mean Business, whose 1,600 plus members have a collective market value of US$24.8 trillion. This is its Theory of Change:

So, come on corporate New Zealand. Get your act together. We must have your serious commitment to help us solve the climate crisis.