On The Internet, Nobody Knows You’re a Terrorist

Comment

The Royal Commission into the March 15 terror attack found Muslims felt their concerns about right-wing extremism were dismissed by police. That’s still happening, Marc Daalder writes

Warning: This article contains distressing content around the March 15 terror attack and graphic descriptions of violence.

On March 2, someone threatened to kill me and the police did nothing about it.

To be fair, there was little they could do. The threat was made on the anonymous 4chan message board, which doesn’t heed law enforcement requests to identify its users, even when they have committed serious crimes. In fact, the threat may well have been made by someone outside of New Zealand – I have no way of knowing and never will.

“Are you guys aware that NZ has its very own subversive J*wish journalist?” the user wrote, posting a link to my Twitter account and pictures of me.

“Best part is he’s at the beehive most days (((working))). It’d be a real shame if someone were to follow him home from there and then go into his house while he’s sleeping and stab him in the heart 6 million times, while wearing gloves and a face mask and leaving without a trace of evidence being left behind.”

This wasn’t my first brush with online extremism. Since June 2019, I have found myself the target of a campaign of online hate and outlandish conspiracy theories. The report of the Royal Commission of inquiry into the March 15 terror attack observes that this experience is all too common in New Zealand. Attempts by the Muslim community to raise it with security services ahead of the mass shooting failed.

For their part, police told me in response to a request for comment that they take online hate seriously. “Speech, violence or threatening behaviour driven by hate is not acceptable and should not be condoned by anyone, whether it has happened online or on the street,” acting Assistant Commissioner Mike Johnson said.

“Police is committed to tackling hate crime, and to improving the way we identify and record offences and incidents. We are also focused on understanding what drives hate crime, doing the right things for victims, as well as holding offenders to account.”

In the end, the terrorist managed to carry out his grievous act despite a history of posting Islamophobic comments online. Reading through what he wrote, I was struck by the fact that it was far more mellow than much of what I see from New Zealand’s extreme right today. This raises the difficulty that online hate poses to law enforcement – how can officials tell the difference between an online racist with no intention to engage in real-life violence and a terrorist?

One of the most famous New Yorker cartoons dates from 1993. It depicts two dogs, one sitting on a desk chair in front of a computer, talking to each other. “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog,” the one seated in front of the computer tells the other.

Even after peeling through layers of anonymity to identify far-right individuals online, it is rarely clear whether they are genuinely planning to commit violent acts. And, as it stands, posting racist, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic and misogynist content on the internet is not a crime.

My own attempts to report threats to rape, assault and kill me to the police have been largely fruitless, further underscoring the challenges facing law enforcement in operating in an online environment and the continuing alienation that victims of online hate experience when they report it to police, even after the March 15 terror attack.

My own conspiracy theory

I remain wary about the worth of writing this article in the first place, as I don’t have any intention of making the release of the Royal Commission report or the March 15 terror attack about me. Nonetheless, it is valuable to personalise the continuing failures of our systems, even after the horrors in Christchurch, for dealing with online hate.

I have previously experienced and written about online hate. In 2016, anonymous Twitter trolls threatened to burn me in an oven or turn me into a lampshade if Trump was elected. I didn’t take it too personally, as the accounts were targeting plenty of of other Jews and showed no signs of trying to locate me.

When I reported on New Zealand’s far-right at the start of 2019, I again received anti-Semitic harassment.

“Tell ya mates to get their hook noses ready gor [sic] the lynching of the century. […] The showers and ovens shall be fired up again,” the moderator of the Facebook group ‘Kiwis United Against the Radical Islamification of New Zealand’ told me in a private message.

As before, I was a low-profile freelance journalist and this individual didn’t seem to have it out for me personally, but rather for Jews in general. It was broadly concerning but I was not worried about my safety.

At the beginning of June 2019, that rapidly changed. Within a few days of far-right conspiracy theorists finding my previous article on New Zealand’s far-right, an elaborate conspiracy theory emerged that positioned me at the centre of the supposed March 15 “hoax”. The theory went viral across far-right groups on Facebook and abuse and threats poured in for several weeks.

In essence, the conspiracy theory is rooted in the belief that, because I was writing about far-right extremism prior to March 15 when few others were, I must have had foreknowledge of what was to come. Given I am from the United States, I must have been sent here as part of a Deep State plot to help Jacinda Ardern impose totalitarian communist control over New Zealand, the theory goes.

It also wraps in my father’s status as a former US diplomat (evidence of a Deep State connection), my mother’s former work during the Clinton administration on stopping biological weapons proliferation (somehow evidence of a connection to the coronavirus) and even my social media antics around Bird of the Year. The conspiracy theorists insist that the memes I post for my bird of choice each year are in fact coded messages to the Prime Minister.

Why, exactly, I would communicate with the Prime Minister via coded messages on a public, bird election-themed Twitter account when I work in Parliament Buildings is unclear, but I long ago realised that there is no point in arguing with these people as if they are rational thinkers.

On its own, the conspiracy theory is bizarre – and deeply offensive to the people affected by the March 15 terror attack, who know this was not a secret government plot but an act of hate-motivated terror. But the volume of posts about me and my family soon grew to outrageous heights – one individual posted about me more than twice a day on average for more than a year, and often more than 10 times in a single day.

Moreover, the conspiracy theorising was accompanied by threats to beat and rape me and attempts to discover where I live. Within a few days, the issue made it to 8chan, the anonymous forum where the March 15 terrorist posted his manifesto, and the threats grew more explicit and more graphic.

“He looks easy enough to kill, a good swing of the hammer to his gut, so he’s shitting blood as you bury a nail through his kippa,” one user wrote about me.

Boomers and neo-Nazis

The escalation in rhetoric was unsurprising, because 8chan represents a different faction of the online far-right than those who most often frequent Facebook.

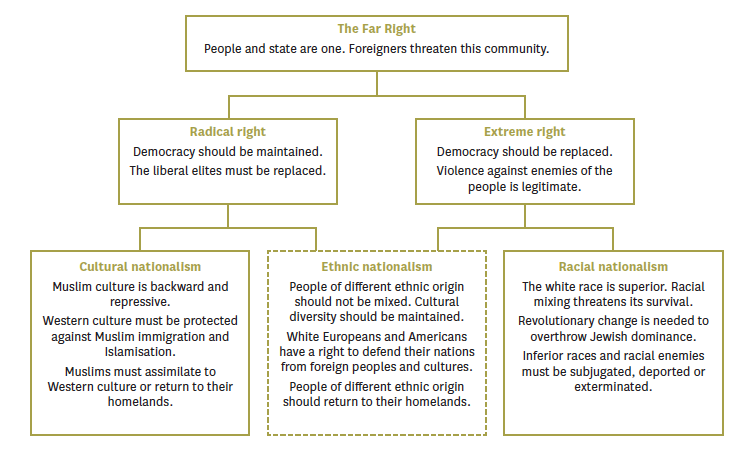

The Royal Commission report presents, with many caveats that these boundaries tend to blur, something of an ideological map of the far-right.

In this framing, cultural nationalists defend Western civilisation, ethnic nationalists defend European civilisation and racial nationalists defend white civilisation. The most prominent target enemies for each group are different, as are their respective dedications to democracy and beliefs around the use of violence.

In my time observing New Zealand’s far-right, I’ve come up with a simpler framework, although the boundaries between my category tend to blur just as often as those in the Royal Commission’s taxonomy.

For me, there are the middle-aged (and older) ‘Facebook far-right’ and the neo-Nazis.

These are of course generalisations, but many of the people who believe the conspiracy theory about me tend to be older, more likely to believe other conspiracy theories like QAnon which tend to be eschewed by violent extremists. They are generally less tech savvy and get their information from Facebook, YouTube and Twitter. Rarely do they visit on the chans – 4chan, 8chan, neinchan and other anonymous message boards rife with gore and child pornography.

They broadly fit into the cultural nationalist category outlined by the Royal Commission. They do not think of themselves as Nazis and are in fact far more likely to ahistorically insist that the Nazis were left-wing, not right-wing. While they are often anti-Semitic, they insist they are not and make a great deal of their political support for the State of Israel.

The neo-Nazis, meanwhile, embrace Nazism and its symbologies. They wear swastikas, iron crosses and sonnenrands. They hate Jews and endorse violence against them and other non-white people. They tend to be younger and more tech savvy and get their information from the chans and complex networks of Discord and Telegram chats. They dismiss conspiracy theories like QAnon as distractions and support Donald Trump as the lesser of two evils, believing he does not go far enough towards supporting white supremacy.

The majority of the harassment I received came from people in the first category. The Marc-Daalder-is-a-Deep-State-agent theory fits neatly into the QAnon view of the world, in which a cabal of political and media elites secretly controls the world, harvesting the blood of child sex slaves for adrenochrome to be used in Satanic rituals, while Donald Trump carries out a secret war against them via hidden mass arrests and posts on an internet forum.

Law enforcement sees the ‘boomer’ far-right as less of a threat than the neo-Nazis. There is some reason for this – they rarely espouse a coherent ideology that calls for violence, instead just threatening to beat someone up or punch them. Moreover, the far-right terrorist plots that have eventuated or been interrupted have largely been carried out by neo-Nazis. There is some evidence this is starting to change – in the United States, a wave of QAnon-related violence has been recorded this year.

In my case, police clearly did not see these individuals as much of a threat. Even when people used their real names on Facebook to engage in threatening and abusive behaviour, the police ultimately told me they had no way of proving it was the same person behind the computer screen. With one exception, police did not so much as reach out to the people launching attacks on me from Facebook and Youtube.

The actual neo-Nazis, meanwhile, are generally far too clever to engage in online behaviour in a way that renders them recognisable.

The March 15 terrorist, for example, used a false Facebook name when he made a handful of Islamophobic comments, expressing outrage about the existence of a Muslim private school, threatening in coded terms to kill an Otago Muslim Association official and implying that the Muslim private school made it easier to target and kill a large number of Muslims.

He ultimately left the group he posted the comments in, with the Royal Commission suspecting he did so because he recognised his comments were a potential breach of operational security.

“Consistently with what seemed to be a general reluctance on his part to acknowledge lapses of operational security, the individual did not accept that his comments would have been of concern to counter‑terrorism agencies. He thought this because of the very large number of similar comments that can be found on the internet,” the Commission found.

Those comments were one of just three things that might have tipped intelligence agencies off to the terrorist’s planning, however, “given what is often said in internet discussions, the comments were described to us [by counter-terrorism professionals] as not being remarkable”.

Police handling inadequate

My experience with the neo-Nazis on 4chan and 8chan was similar. In both instances, police said there was nothing they could do to identify the individuals.

In June in response to the 8chan posts in which people threatened to “bury a nail” in my skull, police told me, “If the article has been posted there, this is a free realm and I am limited in what I can do about this as you have uploaded content to the internet which is being shared. The issue here is that people are able in the online realm to comment as they please and their way of expressing themselves is unfortunately not in a manner which is respectful.”

Later, police confirmed to me that “8Chan is next to impossible for us to trace in terms of anonymous postings and we do not get much assistance from the forum operators”.

In March of this year, after the threat to follow me home, the police simply told me, “After looking at all the available evidence we have not been able to find out who is responsible. Unless more information or evidence is found, we can’t proceed any further with this case.”

However, not all neo-Nazis operate with the same level of operational security as the Christchurch terrorist or use anonymous online forums.

For example, Action Zealandia member Sam Brittenden posted a terror threat against Al-Noor mosque in March and was raided by police days later. However, he was only charged for refusing to hand over his phone password during the raid, not for the threat.

Likewise, I have been able to track down and identify other members of New Zealand’s far right, including a serving Army Reservist (who has since resigned) and an Action Zealandia member who wanted to purchase firearms and launch terror cells. As I understand it, neither have been charged with any crimes, although the latter was spoken to by police around the March 15 anniversary this year.

In part, this highlights the weakness of the legislative framework police are operating in. Their ability to charge people with planning a terror act or engaging in hate speech online or real-life hate crimes is more limited than in other jurisdictions. The Royal Commission report recommends some changes here, although the Government has hinted it may not actually adopt them all despite promising – in principle – to do so.

Police also say they are limited in what they can do in an online environment, particularly on anonymous forums whose moderators won’t collaborate with law enforcement.

This lack of experience with online hate also lead to an alienating and absurdist experience where police recommended I contact Netsafe to help remove the hateful content and online threats, before telling me a few weeks later that the comments and posts in question had now been take down and they could no longer take action against them.

In addition to poor experience with online hate and a weak legislative framework, there is a systemic unwillingness and incapability on the part of police to deal with online hate. This isn’t the fault of individual officers but a broader recognition that the police cannot realistically treat every hateful online message in a New Zealand context as a precursor to violence or terror.

There may well be no good way to tell whether a given comment is a genuine red flag or the output of an online troll. But the systemic refusal to even entertain the possibility of the former makes for an extremely alienating journey through justice system when attempts to address online hate are made.

For the record, Johnson, the acting Assistant Commissioner, said police “reject the assertion there is an unwillingness or incapability on the part of police to deal with online hate. We are absolutely aware of the seriousness of this offending, and we continue to work towards improving staff knowledge, awareness and recording practices, to accurately recognise and record hate crimes and hate incidents, and respond to those seeking our help.”

A significant proportion of his statement dealt with the cataloguing of hate crime data, which is not a subject this article touches on. However, Johnson also said the police “have also established a hate crime working group to lead work to improve systems, process and practice. This has included engagement with other agencies and community groups to coordinate responses in this area. As part of this work trained facilitators from the Evidence Based Policing Centre have run 18 workshops since November with attendees from an array of communities including faith groups, Victim Support, partner agencies and Police staff.

“Police continues to improve its ability to identify and record reported hate crime/incidents and to improve its service response. We have made changes to our national coordination structure, we are training staff on how to recognise and respond to incidents, and on collecting and recording accurate data.”

Experience alienating

In my case, however, police downplayed Holocaust denial and statements like “look at the hook [nose] on that Jew” and “he’s a fucking kike”. Police told me that, “whilst distasteful none of [these posts] are such that they would or are likely to excite hostility against or bring into contempt a group of persons of Jewish origin” – the legal test under the Human Rights Act.

Likewise, police told me that as a journalist I should learnt to expect this level of backlash, even though I was only a freelance journalist at the time, writing around an article a fortnight.

“When considering the alleged threats Police also have to consider what is reasonable harm to a person in your position, that being you are a journalist posting online communications and opinion articles for public consumption and as such it would be expected that a journalist may attract a certain level of public criticism from people that disagree with their views,” police told me.

Direct threats, like a private message to “watch [my] back”, were dismissed by police as “an intended warning by the poster to express dislike about your journalistic activities”.

Later, police would tell me that there is not, in fact, a higher standard for journalists, despite putting the above in writing.

Police also appeared to have a poor understanding of what makes these conspiracy theorists and far-right extremists tick. Later, a more obliging officer got into an argument with one of the people harassing me over whether or not I was in fact a Deep State agent. This entailed an exchange of emails with the individual in which the officer point-by-point analysed my work in an attempt to disprove the theory that I had foreknowledge of the March 15 attack. That was well beyond the remit of the police and did nothing to dispel the (false) notion that I was a a globalist elite using my connections within the police to silence thought-crimes.

In another instance, a woman recognised me in a grocery store and began to shout at me and my partner and film us. When I later reported that to police, alongside the extensive background of my prior harassment, the officer offered to ring her up and ask what her problem with me was. Of course, I already knew what her problem was – she falsely believed I was part of a Deep State pedophile cabal. Needless to say, police ultimately did nothing in that scenario either.

Police never appeared to entertain the notion that one of these people might actually follow through on their threats to find out where I live and kill me. When I asked what sort of support they could provide to help me and my family feel safer, they said I had no reason to feel unsafe. Then they told me that I should watch whether I was being followed home, purchase a home security system and always lock my door at night, before reiterating that I had no reason to feel unsafe.

The sum total of this was to make me feel like I had been unknowingly cast in a Samuel Beckett play, where the world operated by rules that conflicted with my direct experience. Anti-Semitic blood libel dismissed as “distasteful” and death threats downplayed as free speech and fair comment.

This appears to have been an experience shared by Muslim communities prior to March 15. Submitters told the Royal Commission that they did not feel their concerns were heard by police before the terror attack which killed 51 people.

“In some instances they felt that staff did not have the ability to recognise behaviours, signals or patterns of incidents that could signify possible hate crimes or signs of extreme right-wing activity. We were told of instances where people did not see staff writing anything down when making reports. We heard that people rarely received any follow up from New Zealand Police after making reports. This meant that many of the Muslim individuals and communities we heard from felt that New Zealand Police did not take their concerns seriously,” the Commission reported.

“Where New Zealand Police had acted, it is not always clear that they reported back to the complainants about the outcomes of their inquiries. We heard from community members that where New Zealand Police had reported back, this was not always in a way that reassured the complainant that the issue had been thoroughly investigated.”

I also experienced this. At one stage, police informed me they would issue a formal warning for harassment. A couple of days later, they reneged, saying a second check with the legal department had determined there was no grounds for such a warning. At this stage, more than 300 posts had been made about me, my partner or my family by the single individual in question.

There are ways in which police conduct fell short prior to March 15 and in my own case. Unfamiliarity with symbols of far-right extremism and even the online space more broadly meant that things which should have been taken more seriously were downplayed or dismissed.

There are also challenges that fall beyond the remit of the police – the vast amount of hate on the internet requires a far more wide-reaching approach, including genuine action from social media companies. And it will always be difficult for police to tell when or whether a given online comment is indicative of real-life intent to do harm.

Then there’s a grey zone, issues that police could tackle if the legislation backed them but currently find themselves unable to do anything about.

Regardless of which of these categories any given online conduct falls into, there are major improvements that need to be made to the ways police work with victims of online hate. As it stands, the process is alienating and retraumatising, leaving victims with the perception that police don’t see danger in far-right extremism even months after March 15 terror attack.

On the internet, nobody knows if you’re a terrorist, but that doesn’t mean police should assume you aren’t.