Nagorno-Karabakh: Five things to know about the latest crisis | Nagorno-Karabakh

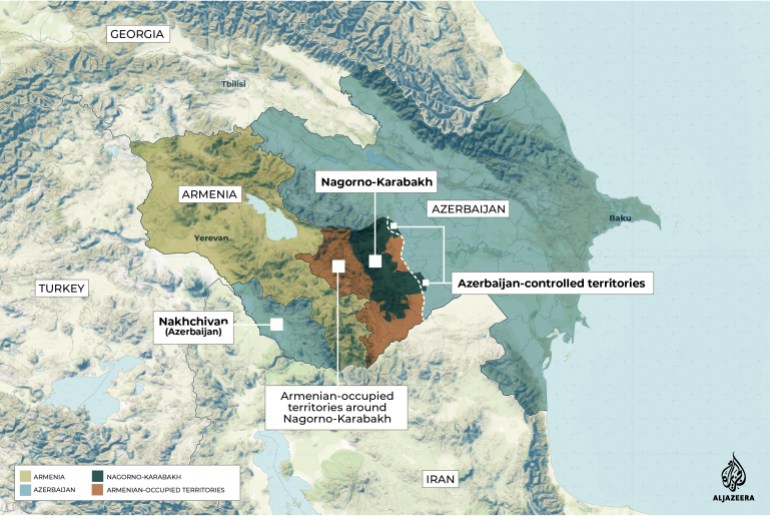

Nagorno-Karabakh is at the heart of a decades-old conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia, both former Soviet republics.

It is internationally recognised as Azerbaijani territory, but is run by ethnic Armenians who either want to secede or join Armenia.

According to Azerbaijan, ethnic Armenians are occupying their land.

Tensions grew in the 1980s. Ethnic nationalism had been frowned upon in Soviet times, so when the Soviet Union dissolved, ethnic Armenians saw a chance to petition to join Armenia.

The result was a bloody war in the 1990s that killed 30,000 and displaced millions. Both sides were accused of attacking civilians, but Azerbaijan bore the greater cost with more deaths and refugees. By the time the war ended, Armenia had seized Nagorno-Karabakh and some surrounding areas.

Known as Artsakh to Armenians, about 150,000 people live in the mountain enclave, with a third of the population in the main city of Stepanakert.

It is about 4,400 square kilometres (2,734 square miles) and lies close to westward oil and gas pipelines.

On September 27, the rivals clashed again, beginning the worst fighting to hit the region since the 1990s. Analysts have warned that this time, the conflict is different mainly because new weapons are being used. There are also fears of an all-out war emerging, drawing in Russia and Turkey.

How did the conflict restart?

As is often the case when the rivals battle, each side blamed the other.

Azerbaijan’s defence industry said it had launched a “counteroffensive to suppress Armenia’s combat activity and ensure the safety of the population”, while Armenia accused Azerbaijan of attacking civilian settlements in Nagorno-Karabakh.

It is very difficult to verify these claims and in the past few weeks, each country has regularly denied the other’s account of attacks and suffering, especially when it comes to hitting civilian areas.

Read more about the information war here.

Why did it begin?

The conflict has always been on the boil. Despite a 1994 ceasefire, clashes have periodically broken out since then. In 2016, hundreds died in four days of fighting. In July this year, dozens on both sides died, mostly troops.

Some analysts have said that the coronavirus pandemic made shuttle diplomacy harder in the months before the clash began. Meanwhile, the pandemic and other issues such as protests in Belarus had taken up international mediators’ attention.

In a recent column for Al Jazeera, Robert M Cutler, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, argued that Nikol Pashinyan, the Armenian prime minister, is increasingly nationalistic and has said he does not recognise the proposed peace settlements known as the Madrid Principles, angering Azerbaijan.

“The Madrid Principles had foreseen and agreed that Yerevan hand over to Azerbaijan the occupied regions around Nagorno-Karabakh. It is clear that if Yerevan had accomplished this undertaking, then the lives of many Armenians and Azerbaijanis would have been spared,” wrote Cutler.

“These terms have been on the table for over a decade, and they are not just Azerbaijan’s. They are supported by the international community and therefore unlikely to change. Azerbaijan now has the upper hand and the military potential to take back all the occupied territories.”

Eduard Chechyan examines the damage in his flat after shelling allegedly by Azerbaijan’s artillery during a military conflict in Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh, October 10, 2020 [AP Photo]

Eduard Chechyan examines the damage in his flat after shelling allegedly by Azerbaijan’s artillery during a military conflict in Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh, October 10, 2020 [AP Photo]What’s the human cost?

In less than a month, at least 63 Azerbaijani civilians and 36 ethnic Armenians have been killed.

Armenia-backed officials in Nagorno-Karabakh say 772 troops have died, while Azerbaijan has not disclosed its military death toll. President Ilham Aliyev has said he would announce the details when the clashes subside.

Many believe the actual toll is far higher than what has so far been reported.

Thousands have reportedly fled Stepanakert to nearby Armenia and some of those who remain live underground in bomb shelters.

People in Azeri towns that have been hit, such as Tartar, have fled to relatively safer areas.

There are major concerns over the extent of the bloodshed in this round of clashes, with new, advanced weaponry in use. Read more about those new weapons here.

What is the international community doing about it?

So far, there have been two attempts at a humanitarian truce that would allow prisoners and the war dead to be swapped. Brokered by international mediators, both have failed.

The first on October 10 was brokered in Russia after marathon talks between the two sides and the second came a week later, after Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov spoke to his Armenian and Azeri counterparts by phone.

In both instances, the warring sides accused one another of breaking the ceasefire hours after the agreed deadlines.

In a wider sense, talks have been ongoing since 1992 under the OSCE Minsk Group, led by its three co-chairs – Russia, France and the United States.

While Russia has good relations with Azerbaijan, Moscow is viewed as supportive of Armenia, although Armenians are concerned that Pashinyan’s small step towards the West may have upset the Kremlin.

Meanwhile, Turkey is Azerbaijan’s most fervent and vocal supporter and Baku wants Ankara at the negotiating table. For its part, Turkey has criticised the Minsk group’s efforts.

What might happen next?

Despite two attempts at a ceasefire, there has been no let-up in the fighting. International players renew their calls for peace on a daily basis.

It appears there is little hope for peace.

In his most recent address to the nation, Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev said: “We will continue to drive the invaders out of our land.”

In a recent tweet, Pashinyan said: “#Artsakh has never been part of independent state of #Azerbajian and the latter’s territorial claims have no base under international law. Prevent Genocide. Recognize #Artsakh.”

But at the same time, both leaders and top officials from both sides continue to talk to international players – the foreign ministers of both countries are headed to the US this week – and in media interviews, Aliyev and Pashinyan suggest a willingness to seek a truce.