More than $600K in unclaimed money found belonging to northern Quebec Cree

Madeleine Kawapit and Jonathan Kitchen are among hundreds of Cree families and entities that have unclaimed and forgotten money in a Revenu Québec fund, a CBC North Cree unit investigation has found.

More than $15,000, in the case of the Kawapit family, and more than $63,000 belonging to the Kitchen family is sitting in a Revenu Québec fund of more than $400 million in unclaimed money belonging to Quebecers.

It’s called the Register of Unclaimed Property, and it’s where money in forgotten bank accounts, pensions and insurance policies, or the proceeds from the sale of other land or property ends up when no one comes forward to claim it.

Experts in unclaimed assets say Revenu Québec isn’t doing enough to find people who have money in the registry, nor to help people access their money once they find out it’s there.

Since unclaimed money goes to pay down the provincial debt, they say Quebec needs to do more to avoid an “appearance of conflict of interest.”

“Why wasn’t I told?” asked Madeleine Kawapit, who lives in the most northern Cree community of Whapmagoostui, a fly-in community 1,200 kilometres north of Montreal.

Why weren’t we told that his money was there?– Madeleine Kawapit, Whapmagoostui resident

The unclaimed money belonged to Kawapit’s late husband, Abraham, who died in 2005. Madeleine suffered a stroke in 2018 and says the money would be a great help to her family.

“Why weren’t we told that his money was there? I would have never known if you hadn’t told me.”

An investigation by the CBC North Cree unit has found more than $600,000 in the fund belonging to the Cree of northern Quebec — people and entities with easily recognizable Cree names.

Without a will

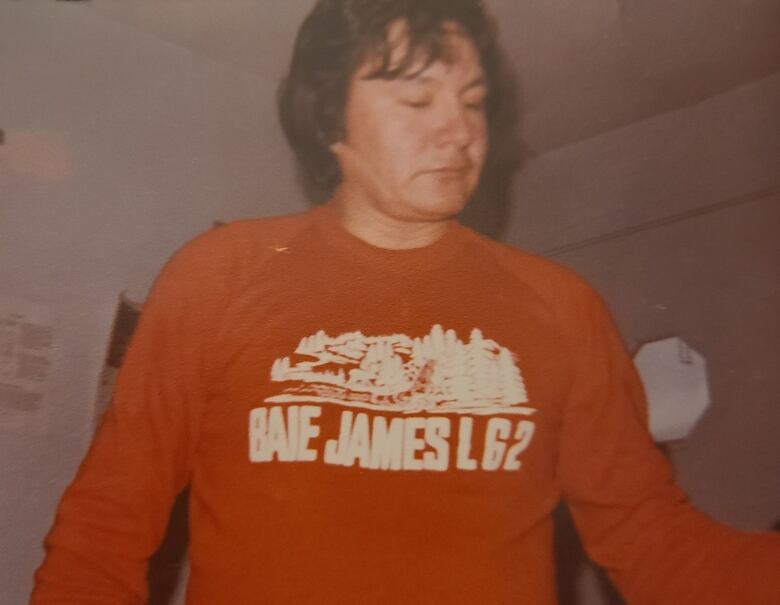

For Jonathan Kitchen and his five siblings, the $63,000 is their late father Samuel’s pension from his job in the forestry sector.

Samuel died of cancer in 2005, without leaving a will.

“We don’t make wills, as they’re called. The Cree don’t do that,” said Kitchen, who has been living in Montreal to receive medical treatment for diabetes.

The Kitchen family didn’t know the money was there until CBC told them.

CBC North Cree unit uncovers more than $600,000 dollars belonging to northern Quebec Cree families in a $400 million unclaimed property fund. The fund is administered by Revenu Québec and some people say the government isn’t doing enough to find people. 0:56

Small amounts lost forever

Revenu Québec has administered the Registry of Unclaimed Property since 2006. Before that, it was administered by the Quebec Public Curator.

After 10 years, any unclaimed assets in the registry get transferred to the Quebec government’s Generations Fund, where it goes toward paying down the province’s debt.

If the total is less than $500, the money is lost forever after 10 years — while claimants can still access larger amounts, if they find out the money is there and are able to make their way through the sometimes arduous process of proving it’s theirs.

By law, Revenu Québec is obliged to maintain a searchable database in French and English, where people can find any unclaimed money belonging to them or their family, according to the ministry’s spokesperson, Geneviève Laurier.

“The Register of Unclaimed Property is promoted in several ways. It is free and easy to view on our website,” said Laurier. She said the ministry regularly publicizes information about the registry on their social media platforms, in French.

Revenu Québec also makes real efforts to track down people with money in the registry, said Laurier.

“We try by all means to trace people. Sometimes, however, you have to understand that it is complicated,” she said.

Revenu Québec is also obliged to publish a list of names once a month, which appears in French in the Gazette officielle du Québec and on the Revenue Ministry’s website.

But what about Quebecers like Madeleine Kawapit and Jonathan Kitchen who don’t speak French well, if at all?

Should Revenu Québec be doing more?

Antoine Aylwin, a Montreal lawyer specializing in estate law, has represented more than 150 families trying to access money in the Register of Unclaimed Property after the 10-year window to claim their funds had closed.

“As of now, there is no obligation, and I don’t think the courts have set out any obligation for Revenu Québec to do anything else other than publish the information,” said Aylwin, who is a partner with the law firm Fasken.

The majority of Quebecers die without a will, said Aylwin, so it’s not unusual for families to be unaware of bank accounts, pensions funds or insurance policies that are rightfully theirs.

“The problem, as I see it, is that Revenu Québec doesn’t have the resources … to do any of this work to find beneficiaries.”

Firm found $460K

One of Antoine Aylwin’s clients is the Mondex Corporation, an international firm that helps beneficiaries recover looted art and unclaimed assets.

The company was involved in two separate Quebec Superior Court cases concerning the Register of Unclaimed Money. In both, the Quebec government was found to have not done enough to find people with money belonging to them.

In one 2009 judgment, the Provencher family of Sherbrooke, Que., was awarded $460,000 plus interest, after Mondex found the money in the register and notified them.

Raymond Provencher, an insurance salesman, died in the 1950s, and at the time, the family was told he was bankrupt.

But by the late 1970s, it was clear that Provencher had actually left a significant estate, said Aylwin.

The court ruled that between the late 1970s and when the family tried to claim the money, the Quebec government should have done more to notify them.

Aylwin said he doesn’t believe there is willful wrongdoing on the part of Revenu Québec, but he does believe it should do more to make sure there’s not even a hint of conflict of interest.

“They’re certainly in a particular situation where if the money is unclaimed, it’s kept by the government,” said Aylwin.

You don’t put money into finding beneficiaries, while at the same time the money is left with the government.– Antoine Aylwin, partner at law firm Fasken

“You don’t put money into finding beneficiaries, while at the same time the money is left with the government.”

Since 2015, $187 million in unclaimed money has been transferred to the Generations Fund.

Whopping finder’s fees

Following the 2009 judgment involving the Provencher family, Mondex proposed taking on the work from the government of tracking down people with money in the registry.

The government refused, and in fact, Revenu Québec warns consumers against the high fees that companies like Mondex can charge.

In the case of the Provencher family, it was 39 per cent of the estate.

“People don’t have to pay a fee to access their unclaimed property. The service is free and available online, so that’s why we don’t currently do business with companies or even subcontractors,” said Laurier.

Laurier said Revenu Québec is able to offer help to families in English to access money they find in the registry.

But is the help really there, and is the money really accessible?

Cree families still without money

After several attempts, Jonathan Kitchen’s family was finally able to get support in English, to ask how to access the $63,000 left to them by their father.

But they are stuck at the first step of the process. They have to track down all the birth certificates of six siblings scattered across Quebec and who, like so many other Indigenous families, are dealing with other things. Kitchen himself spent several months last year in a coma.

“The Quebec government should be pushed to write to [families], so that people will know that there is money there,” said Kitchen, whose sister, Andrea Kitchen, is now trying to gather the paperwork.

As for Madeleine Kawapit, she has moved back to Whapmagoostui but is still grappling with the health consequences of her stroke, and she finds working on the internet difficult. She hasn’t even begun the task of getting access to the $15,000 left by her late husband.

“I am going through a lot right now,” she said. “I’m not working. I had a lot of hardships not having any money.”

Kawapit still can’t believe she wasn’t told about the registry.

“It doesn’t bode well with me. We know that there must be many people who don’t know about it. It’s their right to the money.”

And as time goes on, Revenu Québec continues to charge both families administration fees.

In the case of both the Kitchen and Kawapit families, the fees so far deducted from the estates are, in each case, $1,254.38.