Honduras ‘retakes sovereignty’ by nixing corporate enclaves | Business and Economy News

La Ceiba, Honduras – In a rare display of unanimity, the Honduran Congress voted last month to reverse a controversial law that had facilitated one of the most widely loathed economic projects in this Central American nation.

The law allowed for the creation of special economic development zones, known by the Spanish acronym ZEDEs – semi-autonomous corporate enclaves where investors could govern as though they were independent entities, taking advantage of separate tax schemes, security forces and labour regulations.

While foreign investors and Silicon Valley luminaries had intermittently supported ZEDEs as a driver of economic development, many Hondurans spent years protesting against them, saying the enclaves would displace rural residents while selling off national sovereignty.

The revocation by Congress of the ZEDE law, passed in 2013 and staunchly backed in the ensuing years by the administration of now-imprisoned former President Juan Orlando Hernandez, means that such projects no longer have standing within the framework of the Honduran legal system.

ZEDEs were “the last coup de grace that [the previous government] did to the country: selling off the national territory in pieces”, Maria Carrasco, a Honduran PhD student living in Tegucigalpa, told Al Jazeera. She welcomed the law’s revocation, saying the controversial project had been “the icing on the cake” after years of government corruption and mismanagement.

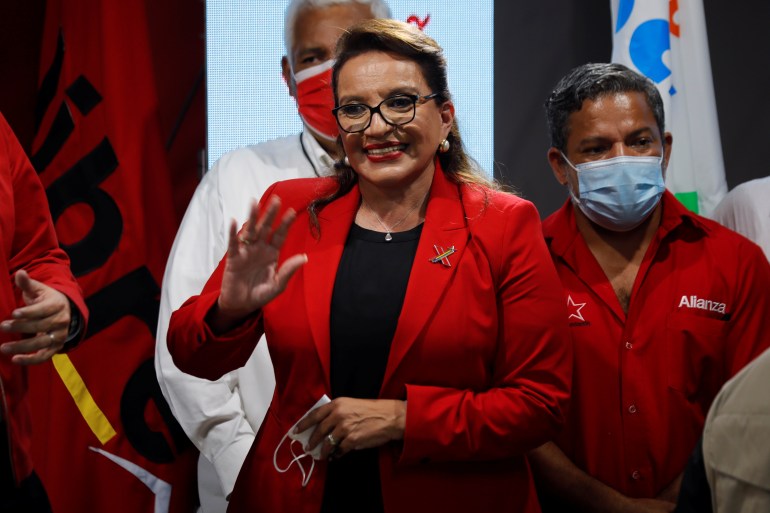

Xiomara Castro, the left-wing president inaugurated in January, thanked Congress for “repealing the criminal ZEDEs and defeating those who tried to steal our sovereignty”. The first female head of state in Honduras, Castro had made revocation of the ZEDE law a signature campaign promise.

‘Proceeding confidently’

Exactly how the repeal will affect companies that bought into the ZEDE scheme over the past decade is not yet clear.

In a news release following the vote, Honduras Prospera, a United States-based investor, said it had “every intention of proceeding confidently with plans to invest hundreds of millions of dollars and to create tens of thousands of good-paying jobs in Honduras in reliance upon its acquired rights under the ZEDE framework”. A denial of those rights by the state “would plainly violate its obligations under international and domestic law”, the company added.

Fernando Garcia, the presidential commissioner tasked with opposing the ZEDEs, told Honduran media that the Castro administration was preparing an executive decree to allow businesses within existing ZEDEs to continue operating, under the condition that they submit themselves to new economic regimes.

There were several functioning ZEDEs in Honduras, including Ciudad Morazan, in the city of Choloma; Prospera, along the north coast; and Orquidea, in the southern department of Choluteca.

“Despite the fact that they [ZEDEs] have disrespected democracy in Honduras, we won’t act in the same way,” Garcia told the Contracorriente news website. “We are superior as a state, as a sovereign and as a government, so we’ll give them the opportunity of establishing themselves in accordance with existing legal regimes in the country.”

While proponents of ZEDEs have argued they would create an environment free from government corruption and bureaucratic red tape, ultimately bringing jobs and money to impoverished regions of Honduras, opponents and social activists say such claims were exaggerated.

“The decision to revoke the ZEDEs sends an important message, and was a brave decision by the Honduran Congress to retake the sovereignty of our country and the totality of its territory,” Leonel George, a human rights defender in Tocoa, told Al Jazeera.

The displacement of the Afro-Indigenous Garifuna community, situated in pristine coastal territory where a number of ZEDEs have already been launched, could have been accelerated via the establishment of the enclaves, he added: “Lots of the rights of Honduran citizens have been violated by these projects over the past few years … The population here sees this [reversal] as a really positive thing.”

Predecessors to the ZEDE system failed to make it through the Honduran legal system. A similar 2011 proposal for “model cities” was struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, which ruled the scheme would violate Honduran territorial sovereignty. But Congress, then led by Hernandez, subsequently removed four of the five Supreme Court justices, ostensibly as part of an anti-corruption drive. The ZEDE law followed in 2013.

Lack of popular support

Hernandez, one of the strongest political advocates of the enclaves, was recently arrested and extradited to the US on charges of drug trafficking; he has denied any wrongdoing. Hernandez’s brother, a former Honduran congressman, was sentenced last year to life in prison after being convicted of drug trafficking.

For some members of Congress, it was not the concept of the ZEDEs per se, but rather their sheer unpopularity among the Honduran population that pushed them to vote for the law’s repeal.

Conservative Congress member Marco Midence, who belongs to the National Party of Honduras, said his party believes in the ZEDEs’ stated purpose of job creation and bringing foreign investment to the country. But party members ultimately opted to throw in the towel after acknowledging the project lacked critical support among the broader population.

“We always ask in the legislative chamber that we respect the ZEDEs that already exist,” Midence told Al Jazeera.

“But at the end of the day, the subject is one that polarises the Honduran population. So now, we’re going to look for other creative mechanisms and fiscal regimes to continue bringing investment to Honduras and generating more employment for the population.”