flogging the family silver for $2

ReadingRoom

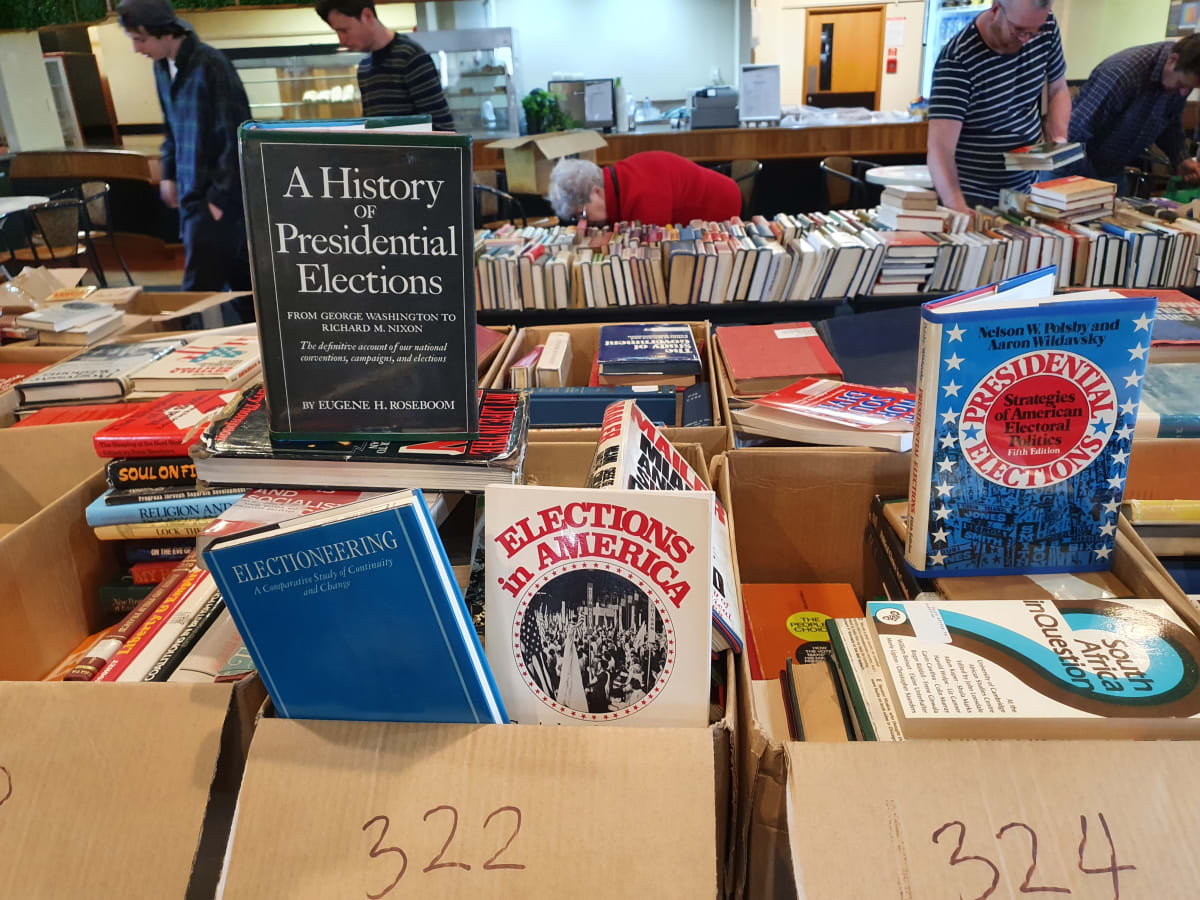

Chris Bourke reports from the disgrace of the National Library’s dumping of 57,000 books at a charity sale in Trentham

The biggest surprise at this week’s sale of the National Library of New Zealand’s overseas published books is how well read they are. The pages have that thick, furry texture from years of being turned by countless readers and researchers. These books have not just been read, their contents have been absorbed.

There are coffee stains, bent corners, nappy-yellow marks where Sellotape has dried up and dropped away. But the books smell great. Unlike the musty books many will soon be joining in second-hand book shops, these copies have been stored properly since the day they arrived in New Zealand. Many still have that confident, “I was printed in the US on good paper” scent that post-war books from Britain never quite managed.

This sale is the first of what the National Library hopes will be a series of sales that will clear space for future publications from New Zealand. Current storage is declining for a variety of reasons that can be summed up in one word: policy. Decisions have been made not to replace a leaking storage building with other unused government buildings, because a recent policy insists that books published overseas over 20 years ago are largely irrelevant to New Zealand researchers. There was no need to go in to bat for a fairer cut of the Internal Affairs budget.

ReadingRoom reported in October that the National Library undertook not to schedule more book sales until after the election, when the incoming government – and a new minister – could be briefed on the issue. That promise did not include this week’s sale; like Elvis, these books had already left the building. They were no longer owned by the National Library – the taxpayers – but by Lions. The problem of “rehoming” was solved by shifting them to a neighbour’s garage; by “weeding” using Roundup.

The location is a rundown function room at Trentham racecourse, near Upper Hutt. These books are less than 10 percent of the intended 625,000 to depart permanently from the shelves and storage spaces of the nation’s shared library. The room is not nearly big enough: there are several long rows of trestle tables with books stacked spines outwards. Underneath them are large boxes waiting their turn. Around the walls, sometimes stacked four high, four wide and four deep, are still more large unopened boxes stuffed with books.

These once-loved information sources now look very much unloved. They have been hurriedly packed, roughly in the order of the Dewey decimal system. As anyone who has moved house knows, boxes have to be filled so books have to be arranged by size, not order. With each new handling, even the rough sense of order evaporates. When the public arrives, they will be taking to heart every librarians’ request: please don’t reshelve the books. The result is chaos, a library floor after a major earthquake.

Wednesday evening was the invitation-only opening for book dealers. I attended for a South Island dealer. He is interested in books about books and publishing, and detailed bibliographies – book-length, annotated lists of books. In libraries, they may be on the shelves that are rarely visited by general readers, but they are the starting point for any researcher.

These 57,000 books are from the 000-350 sections of the Dewey system. At the 000 end are bibliographies, library science, computer manuals, essays, journalism, and books about rare books. In 100 and 200, philosophy and religions, and in the 300s are social sciences.

There are acres of sociology books; those stacked vertically are like hay bales. Irrelevant studies of adolescents, gender issues, civil rights, politics, apartheid, gay studies, censorship, prejudice… The range of topics is overwhelming, the sub-sets within subjects mind-boggling. For sociologists of Upper Hutt and wider Wellington, who will browse the books after the dealers have been through, this is the quinella of their dreams.

The dealers – there are about 20 of them – are going through them as methodically as possible in such haphazard conditions. Which means quick, frenzied decision making. It’s a pig in a poke if you’re after a specific book. A box might have 301 scrawled on the side (sociology and anthropology), but there are dozens like that, with a few strays thrown in to fill up the box.

Lions and Rotary are doing their best. Given the books by National Library to sell, raising funds for a new Wellington Regional Children’s Hospital, the volunteers were still loading boxes of trucks in the afternoon of the opening night. At this stage, their demeanour could not be more helpful.

“Have you joined the vultures?” a Wellington second-hand bookseller says to me. “No, I’m here to save a few for some specialists,” I say. He’s using black humour; he is dismayed that this collection is being disposed of, especially using the official euphemism “rehomed”. He knows how many of these books will never be given a second shelf life.

One dealer is more gung ho. He has shops in two cities, and within an hour has somehow filled 30 boxes for a friendly Lion to wheel out the back on a trolley. He offered to buy the lot, he says, and I’m in no doubt he means not just these 57,000 but all 625,000. But the Library wouldn’t do it; he can’t understand it. Last time a “cull” like this happened, in 1999, his store made a tender. But the sale became controversial, he says. People thought there were items from the Alexander Turnbull Library, “which was completely wrong”. He’s right about that, at least.

A researcher lucks upon a stack of irrelevant books on US elections. Among them are New Journalism classics from 1968: Joe McGinnis’s The Selling of a President, Norman Mailer’s The Siege of Chicago. Bestsellers both, so available elsewhere, but he buys these first editions to give back to the Library if the winds change.

As a writer friend says, there’s a wilful cultural amnesia here. A denial of these books usefulness, and their relevance to New Zealanders. A belief in digitalisation that is not supported by reality; the users of the books, if consulted, could have made that case. The Library says 25 percent of the books are already digitised – which, it needs saying repeatedly, means that 75 percent aren’t. And many won’t be, thanks to global extensions of copyright led by content owners such as Walt Disney. The Mickey Mouse lobby is well funded.

Any book in this room can be picked up and ridiculed for its lack of relevance. It’s the reductio ad absurdum argument. Those of us who failed Latin have to look up a dictionary and learn it means making a ridiculous analogy to prove an opposite point. A library association lobbyist on ReadingRoom recently used this technique, listing Arthur Sweet’s Ornamental Shrubs and Trees: Their selection and pruning (1935) as an example. Fair point, was my kneejerk reaction. Then a friend wrote reminding me she was a gardening historian: like food history, a boom area in this era of staying close to home.

She has five different editions of the Yates Gardening Guide, covering 40 years, and she uses them all. What the lobbyist doesn’t seem to understand, she says, is that new knowledge is made from old knowledge. Books such as Sweet’s guide to pruning have an “abiding influence and significance to New Zealand heritage gardeners.” She refers to them often for magazine articles that reach thousands of readers. “I could tell similar stories about old cookbooks, and the wonderful new knowledge created by archaeologist David Veart (First Catch Your Weka) and art gallery curator Alexa Johnston (Ladies A Plate).”

Family history – another boom area in research – is one of the few sections of the overseas collection that is being kept by the Library. But what use is genealogy without context? I would like to write a book about Irish immigrants to New Zealand, including why they came here. In this Trentham disposal – somewhere – are many that would be useful: books on the social origins of the Irish land war, views of the Irish peasantry 1800-1916 (my lot arrived in 1868), the “eccentric lives” of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, education among the Irish working class in the 1800s, women in Irish culture “from earliest times”, Irish travellers and tinkers – and, of course, religion. Actual history books on the topic are destined for a future sale.

The National Library contributes enormously to New Zealand life, culture and knowledge. I think of the careful stewardship of the Alexander Turnbull Library (protected, luckily, by statute), its support of school and community libraries, the Archive of New Zealand Music, the hireage of music scores to orchestras nationwide, the oral history archive, its harvesting of lost websites, its help to publishers needing cost-effective images, the work for readers with print disabilities – and its understanding and embrace of taonga Māori and history.

As the nation’s library faces its future, the same wisdom of Library pioneers such as Johannes Andersen and Geoffrey Alley needs to be at work. Who? Andersen was a Danish polymath, the Turnbull’s first librarian, a taonga Māori collector; Alley was the first National Librarian, and – will this ever happen again? – an All Black. They were not just custodians, but researchers, endlessly curious and not insular. Custodians need to think beyond good housekeeping, “bringing joy” with few overseas books and tidier shelves. Their customers, curious by definition, will wonder why the digital utopia they have been promised required deleting so much knowledge from the past.