Fashion Is Dead, Long Live Fashion! – WWD

Ever wonder who those people are, the ones trying to get into runway shows or posing for photos on the pavements of London, Paris and Milan? Not the VIP guests, buyers, or media but the flamingos flashing their feathers and hoping to fly past the PRs and land a seat (although they’ll settle for standing).

“I never have a ticket, never! Darling, I AM the ticket,” says one hopeful on her way to a show in Gianluca Matarrese’s new documentary film “Fashion Babylon,” which has been doing the festival circuit and will premiere in Milan and Paris this summer before airing on France Télévisions.

That hopeful is Michelle Elie, the Comme des Garçons collector, jewelry designer and one of three characters who Matarrese follows in this film that’s all about ego, persistence and fashion’s power to transform, and wreak havoc, in people’s lives.

The film is also about fashion’s enduring power to attract outsiders. In addition to Elie, Matarrese tails Casey Spooner, the American musician, artist and onetime presidential hopeful, and Violet Chachki, the burlesque performer, model and a winner of “RuPaul’s Drag Race.”

Violet Chachki in “Fashion Babylon.”

Courtesy

Matarrese films all three doing the Paris and Milan fashion show circuits season after season, getting themselves photographed and hustling for work — or even just a ticket to the show.

The film culminates with Jean Paul Gaultier’s farewell haute couture show at the Théâtre du Châtelet, which took place just weeks before COVID-19 strikes in early 2020.

Soon, those spectacular live events that were like oxygen to Spooner, Chachki and Elie would be replaced by digital ones, or discreet presentations with fewer side shows on the pavement.

Matarrese, 42, an Italian living in Paris, says he originally wanted to look at fashion’s “never-ending party” and show his characters in “a magical land, a looking-glass world, an Atlantis — a Babylon.” But the narrative rapidly swerved, due partly to COVID-19, and Matarrese would eventually make a film about what he saw as the end of an era.

He believes that true creators like Gaultier are disappearing, and quotes Giorgio Armani’s 2020 letter to WWD in the film. At the start of the pandemic, Armani wrote that fashion needed to slow down and to rediscover its roots in craft and creativity, rather than focus on splashy events and marketing.

Michelle Elie dressed in Comme des Garçons on the Paris Métro.

Courtesy

In a Zoom interview from Copenhagen, where he was recently promoting the film, Matarrese says that creative whimsy has given way to business concerns, and believes fashion is becoming a quieter and more sober affair.

“There is no more circus carnival, like before, and there’s more awareness for sure. I think fashion is evolving in other directions, with digital shows, for example,” says Matarrese.

He doesn’t blame COVID-19 entirely. “It’s something that would have happened eventually,” he says.

Matarrese followed Spooner, Chachki and Elie for around three years, and says he usually starts his projects by filming — and then seeing what happens. “I start with small stories, and then go bigger,” he says. “And I’m always attracted to collapses.”

In 2019 he made a documentary called “Fuori Tutto,” or “Everything Must Go,” about the collapse of his family’s footwear store chain in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the rise of online shopping.

Recently he made “La Dernière Séance,” or “The Last Chapter,” about a BDSM master retiring from a career in erotic bondage, dominance, submission and sadomasochism. The film won the Queer Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival last September.

With “Fashion Babylon,” he wanted to look at the industry not through the lens of designers, the media or the thousands of people backstage who keep the business ticking, but from the perspective of those on the edge, the people on the pavement who are hoping to use the shows, and their fragile relationships with brands and designers, to make money, indulge their passions, or further their careers.

“Fashion Babylon” is dark, although it has some funny moments, like when Chachki declares, “I can’t sit down in this” as she changes into a sparkly jumpsuit in the back of a car on the way to a show.

“How am I going to watch the show if I can’t sit down?” she asks Spooner. The artist, who’s midway through his own wardrobe switch, deadpans: “Well, we’re probably going to be standing anyway.”

Casey Spooner in head-to-toe Fendi in “Fashion Babylon.”

Courtesy

The film also digs into the characters’ pasts to figure out why they’re doing what they do.

“I always had a problem with my hips as a model. I was a Black girl modeling, and every girl was always skinny and flat — no bums whatsoever. Whenever I had a booking, I was always afraid I’d get canceled because of my height and my size,” says Elie, talking about why she collects Comme des Garçons.

Rei Kawakubo’s bulbous silhouettes, exaggerated proportions and sculptural designs, Elie adds, “solved all of my years of struggle with my body. A lot of women are so concerned about looking beautiful, skinny, slim and [Kawakubo] deforms you. She creates beauty within the deformalities [sic.], and re-questions what beauty is.”

The film also follows Elie putting together her 2020 show “Life Doesn’t Frighten Me: Michelle Elie Wears Comme des Garçons,” an exhibition at the Museum Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt.

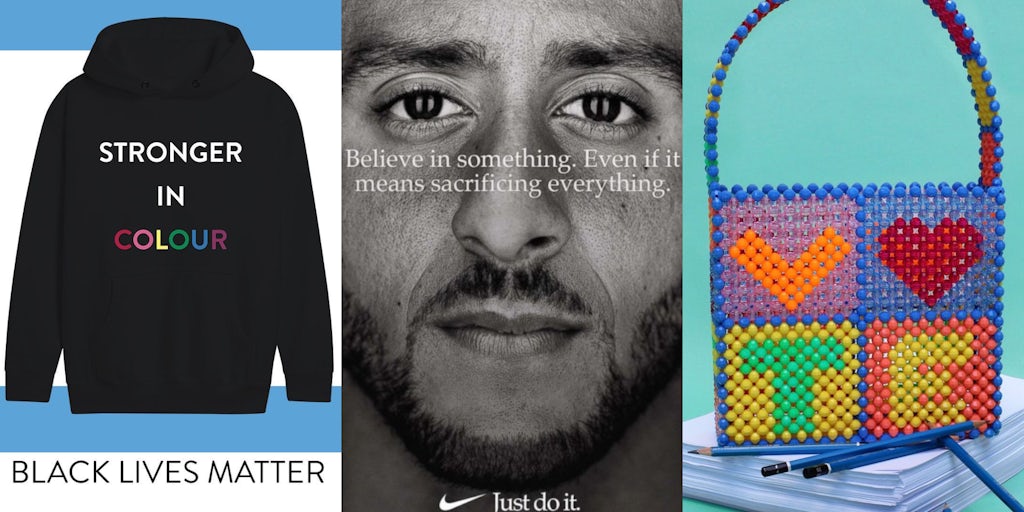

One of the posters for “Fashion Babylon.”

Courtesy Image

And while life may not frighten her, Elie is shaken after a brief encounter with Kawakubo backstage after a show.

Encased in an enormous white mountain of a dress that restricts her movement, Elie greets the designer and her husband Adrian Joffe, and then returns home, only to collapse on a sofa.

“I have to come down, I have to come down,” she says, and then starts to cry.

Mostly, the documentary is heartbreaking, with all three dressed up with nowhere to go, or disappointed once they get there.

At one point it seems like Spooner is in with the folks at Fendi — and with Silvia Venturini Fendi, who makes a brief appearance in the film. The brand pays him $10,000 to attend a show in Milan and get photographed in FF logos and furs, but then it all goes wrong.

“This is NOT like a Prada fitting,” Spooner whispers to Elie over a glass of bubbly as he chooses outfits from the Fendi showroom in Milan. He’s clearly disappointed by the informality of the whole affair.

“The Fendi thing started amazing,” Spooner says after appearing in the front row — and on the pavement ahead of the show.

“I negotiated that I would wear a look, but then they were angry that I took so much. I didn’t realize I was taking a lot. But I wear it, and I get photographed and so I am advertising. It’s not like I’m taking a gift, I’m giving a service,” he argues.

Casey Spooner and Violet Chachki in the front row in “Fashion Babylon.”

Courtesy

Even with the ad money coming in, Spooner can’t pay his rent in Paris and tries to borrow some from Chachki, who’s 20 years his junior.

At one point he admits that keeping up the illusion of celebrity is “exhausting. I love the fantasy, but sometimes it takes its toll. I’m tired, I’m rundown, I’m broke and I’m lonely,” he says.

Chachki is also disappointed by fashion. She’s a talented artist, and Matarrese even films one of her burlesque shows in Paris (including an aerial performance). But she still has to fight sometimes to get into shows and, at the last minute, she’s canceled from the runway lineup of Gaultier’s farewell extravaganza.

“Gaultier has resonated with me forever!” she complains to Dita Von Teese in a phone call. “I feel completely taken advantage of, and disrespected as an artist.”

Von Teese urges Chachki to take the high road and attend the show, where she’s been offered a front-row perch between Duran Duran and Rick Owens. But it’s not to be.

“Goodbye, Paris — forever,” says Chachki, whose real name is Jason Dardo, and who later leaves the hotel dressed not in drag but in trousers, a fuzzy jacket and a baseball cap.

Viewers see her riding away in a silver Uber van with a big dent in the door.

Gianluca Matarrese, the writer and director of “Fashion Babylon.”

Picasa

Matarrese said ever since his days in television (he worked as a writer and director for comedy series on France’s OCS pay-TV networks) he’d wanted to turn his camera on the fashion world.

After spending time with Elie, Spooner and Chachki, he finally understood why.

“I was interested in this world because there was so much of me in it, my desire for recognition, my dream of being loved, which is what all artists desire,” he says.

Matarrese is also a compulsive storyteller, and believes that weaving a tale makes life more interesting.

“I’m always looking for stories to tell — anything can be a story. I talk about this with my therapist all the time. I like transposing everything to a story. Does that mean I’m sick?” he asks.

While this fashion film may be edged with sadness, the message is ultimately an uplifting one.

Matarrese’s characters may be having a tough time, but they’re survivors, and so is fashion. Designers will come and go, but the industry will flourish, albeit with smaller shows, and fewer tickets.

As for the strivers, the artists and creators, they never go out of fashion.