Elderly homes in Australia under fire after high COVID-19 deaths | Australia News

Melbourne, Australia – Neville Vaughan was the “life of the party” at the aged care home, where he lived in Melbourne’s northern suburbs.

He loved to sing and dance. In February, he even joined the festivities celebrating the 18th birthday of his granddaughter, Rebecca.

But despite being remembered as a very socialble person, Vaughn died alone after contracting the coronavirus, also known as COVID-19, at the nursing home.

Suffering from dementia, the 80-year-old had a hard time comprehending why his family had to socially distance from him, including his wife of 61 years, Margaret.

“My grandmother said that they would have to sit on separate sides of the room, but he would try to come up and hug her,” Rebecca told Al Jazeera.

“And he would say: ‘Why can’t I hug you or give you a kiss?’”

Eventually, visits were banned, and the last time Vaughn saw his wife was through FaceTime at the hospital, where he was transferred after he was diagnosed with COVID-19.

Neville died on August 16, a week before his 81st birthday.

Allegations of mismanagement

Globally, Australia has been praised for largely containing the coronavirus, with an estimated 27,000 cases and 886 deaths as of Thursday.

Yet the elderly account for a staggering 665 of those deaths; people who had picked up the infection in the nursing homes where they were supposed to feel safe. Of those, 635 of the deaths were in the state of Victoria – including Vaughn.

The large number of casualties in Victoria has been attributed to the alleged “mismanagement” of the state’s quarantine system, from which a reported 99 percent of new cases spread.

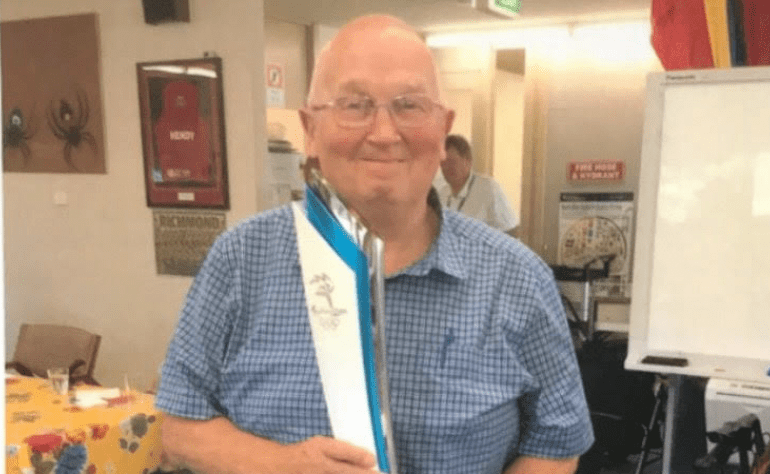

Neville Vaughn died on August 16, a week before his 81st birthday [Courtesy of Rebecca Vaughan/Al Jazeera]

Neville Vaughn died on August 16, a week before his 81st birthday [Courtesy of Rebecca Vaughan/Al Jazeera]The deaths, especially among the aged population, has left many families with unanswered questions. They are asking why the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) was not made compulsory in the early stages of the pandemic and why infection control measures did not stop COVID-19’s initial spread.

Rebecca, a nursing student at Victoria University, said that more should have been done at the start of the pandemic, adding that Australia already had plenty of warning after the debacle in Italy among the elderly.

Yet the aged care sector was slow to respond, she said, pointing out that some facilities only made PPEs mandatory in July or August.

“I find it hard to think that even possibly in March or April there was no PPE [being used by aged care staff],” said Rebecca’s mother Kelly.

‘Tale of neglect’

The outbreak of COVID-19 in aged care facilities in Australia is not the first controversy to grip the aged care sector.

In 2018, a Royal Commission described the industry as “shocking tale of neglect” that “diminishes Australia as a nation” in an interim report.

The commission also revealed alleged cases of sexual abuse as well as cost-cutting measures designed to maximise profits.

Following the coronavirus outbreak, the commission also started looking into how aged care facilities handled the pandemic.

It found that “none of the problems that have been associated with the response of the aged care sector to COVID-19 was unforeseeable”.

This included gaps in workforce numbers, lack of access to PPE and training and a lack of clinical skills, especially in infection control.

Systemic flaws

Australia’s federal government provides 80 percent of the aged care sector’s budget, amounting to about $14.38bn, but the facilities are run by the private sector [File: Joel Carrett/EPA]

Australia’s federal government provides 80 percent of the aged care sector’s budget, amounting to about $14.38bn, but the facilities are run by the private sector [File: Joel Carrett/EPA]Critics of Australia’s aged care industry say that the pandemic simply exposed already existing flaws in the system.

While Australia’s federal government provides 80 percent of the aged care sector’s funding, amounting to about 20 billion Australian dollars ($14.38bn), the facilities themselves are run by the private sector as a competitive, profit-driven market.

And it is this market-based system that should be blamed, according to aged care advocate, Sarah Russell.

She told Al Jazeera that that the sector created “an environment that supported the profits of providers. It didn’t actually have a human rights focus on the older person.”

The shift to a consumer-based model in 1997 brought in a lot of private equity and real estate companies with no experience looking after older people, she said.

“They were there to make money for their shareholders.”

This meant cutting costs wherever possible, including essential supplies such as PPE and adult diapers, and hiring of casual carers with a few weeks’ training, as opposed to fully qualified nurses.

The Royal Commission also revealed that the government regulator on aged care and safety gave perfect compliance ratings in 2018 and 2019 to three aged care facilities which this year reported severe outbreaks of COVID-19.

Among the facilities given a perfect compliance rating was the nursing home where Vaughan died.

According to the Royal Commission, aged care service providers said overwhelmingly in testimony that they were ready for an outbreak.

Yet despite their response, a separate study conducted by the Australian Nurses and Midwifery Federation found that almost half of the aged care nursing staff said they did not feel prepared in dealing with the disease.

Ad hoc response

Jess’ (not her real name) father, 73, tested positive on August 18 in another aged care facility in Melbourne.

She said that despite assurance from staff that her father was doing well and had only developed a slight fever, he died five days later.

Correspondence from the provider to Jess’s family reviewed by Al Jazeera showed that the home detected its first case of COVID-19 on July 20.

Medical workers evacuate a resident from the Epping Gardens aged care facility in the Melbourne suburb of Epping during the height of the pandemic in the country [File: William West/AFP]

Medical workers evacuate a resident from the Epping Gardens aged care facility in the Melbourne suburb of Epping during the height of the pandemic in the country [File: William West/AFP]The correspondence also revealed that it was only on this date that staff began wearing PPE.

Unlike Vaughan, Jess’ father, who had dementia, was not transferred to a hospital on testing positive, but was placed in a “COVID ward” in the aged care facility itself.

Jess is angry at what seemed to be the ad hoc response of the staff to the pandemic.

“It was very clear that staff didn’t know what was going on,” she said. “I don’t believe that they really understood what they were dealing with.”

‘Full range of regulatory powers’

In a statement to Al Jazeera, Australia’s Aged Care Quality and Safety Commissioner Janet Anderson said that since March, regulators had undertaken 965 unannounced visits to residential aged care facilities nationally in response to the pandemic.

These visits included, but were not limited to, infection control spot checks, she said.

Anderson further said that her office had “been using the full range of our regulatory powers” to ensure that providers meet their obligations with respect to the “Quality Standards” of aged care.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson from the national Department of Health said that the government also created in February 2020 a special COVID-19 response unit to deal with the pandemic.

The department also said that on August 21, the federal government endorsed a plan “to boost aged care preparedness for rapid emergency response to COVID-19.”

This plan includes face-to-face infection control, the compulsory wearing of protective masks and an audit of state and territory aged care emergency response capabilities.

The homes where Jess’s grandfather and Vaughn spent their final years did not respond to Al Jazeera’s request for comment.

For the families of those who died during the pandemic, the question remains as to why it has taken a Royal Commission, so many plans and so many deaths, to address the problem.

“We should have really protected our elderly population and the nursing homes more,” said Rebecca, Vaughn’s granddaughter.

“That would have really prevented a lot of deaths.”