Comparing Covid: How New Zealand Stacks Up

Comment

Michael Hanne takes a close look at the numbers to compare New Zealand’s Covid response to similarly-sized European nations

New Zealand government ministers very rarely comment on the pandemic policies of other countries (except, occasionally, Australia). So, it was quite a surprise to hear Jacinda Ardern draw attention in a press conference in November to the fact that Ireland, which had recently relaxed restrictions on mobility and social interactions, was reimposing them because of rising case numbers. She suggested that New Zealanders would not want restrictions in this country to be relaxed prematurely, only to have them reimposed when the situation deteriorates.

Ireland (population, like New Zealand, five million) had been placed top in the world in October in the Covid Resilience Ranking of “best places to be during the pandemic”, published by Bloomberg News. (It dropped to number four in November). New Zealand, which had held that top position for many months in 2020, as it kept infection and death rates very low, has been steadily demoted, during this year, as our Government, with the arrival of the Delta variant, reinstated controls on economic activity and international travel, and is currently 36th.

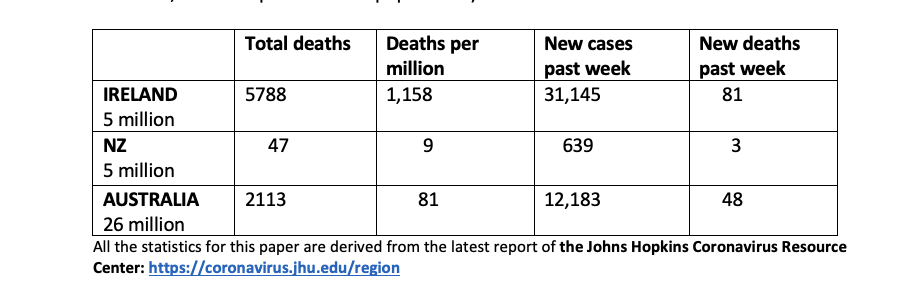

Given Bloomberg’s positive assessment of the path that Ireland has taken through the pandemic and this recent U-turn in policy by Irish authorities, New Zealanders may be startled to see the current statistics for Ireland, in terms not only of total deaths but new cases and new deaths, especially when compared with New Zealand (and Australia which is now rated number 33 by Bloomberg). (The clearest way of comparing death rates across countries, is deaths per million of population.)

Not only is the overall death rate in Ireland 129 times higher than in New Zealand, but deaths over the last week are 27 times higher than ours. The new case rate for Ireland suggests the spread is now pretty much out of control. Jacinda Ardern’s point that we do not want to follow them down the track they have taken is surely something of an understatement.

Over recent months, New Zealand media have brought quite a few Covid stories from small western European countries (including Austria, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Sweden). We have had news of: sharply rising case numbers and deaths (some countries call it the fourth wave, others the fifth); relaxation of restrictions, which is generally followed by their reimposition; use (or not) of vaccination passports and sanctions against the unvaccinated; and, increasingly in some countries, protests against these moves. Because they are small (under 20 million population) and have health and welfare systems quite like our own, it should be possible to make systematic comparisons between the performance of these countries in response to the pandemic and the New Zealand response. Even so, nowhere in the New Zealand media have we been able to get an overview of how these countries compare with each other or with New Zealand in their handling of the pandemic to date.

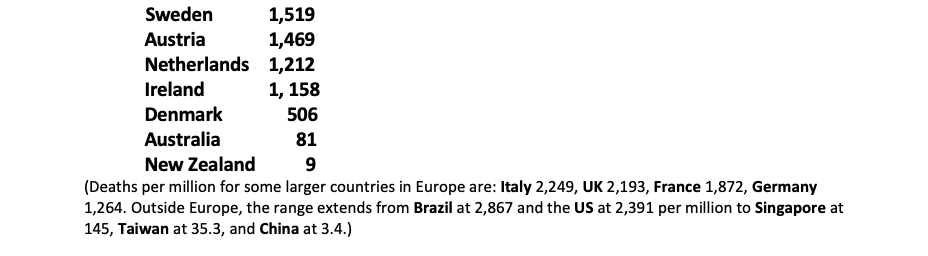

So, how do the statistics for Ireland compare with those of other small Western European countries? Here are figures for deaths per million for a range of these countries, from worst to best, alongside those of New Zealand and Australia.

The gap between the Australian and New Zealand figures and those for most of these countries is staggering. Only Denmark has a death rate anywhere near as low as the Australian/New Zealand rates. (Even so, the Danish death rate is six times the Australian death rate and 56 times the New Zealand rate.)

Ardern and her ministers have been careful throughout not to quote comparative statistics with other countries, doubtless because they do not want to appear to be crowing about our relative success. (They do occasionally mention that we have the best record in the OECD, but without being more specific.) This does have the consequence, however, of limiting New Zealanders’ appreciation of just how successful this country and Australia have been and continue to be.

It will take epidemiologists and public health historians to tease out in detail just how each country slashed a different medical track through the pandemic jungle. Nevertheless, it is possible to bring a socio-political eye to bear on these phenomena – and derive some very clear lessons for New Zealand.

Public policy specialists refer to three main ways by which a government may seek to shape public behaviour: ‘carrots’ (economic grants and subsidies), ‘sticks’ (regulations), and ‘sermons’ (non-binding recommendations). In a major crisis, it is crucial that all three instruments are used consistently and in concert. More specifically, in the case of a pandemic, governments must develop policies informed by medical and other experts and give them the opportunity to communicate key information to the public. Behind each of the disastrous cases reflected by these tables, it is possible to find a different cluster of flaws.

The high total death toll for Sweden (currently ranked number eight by Bloomberg) stems primarily from the initial disastrous decision by the Swedish authorities to forgo the rules and restrictions introduced by most other European countries, instead allowing individuals to decide how to handle the risk personally. (In other words, Sweden relied on ‘sermons’ and a few ‘carrots,’ such as business subsidies, in its early response to Covid.)

Two features of the Swedish constitution lay behind this decision: government ministers are not permitted to direct or overrule the experts in their ministries on public policies, and measures such as lockdowns and curfews are viewed as being violations of people’s freedom of movement. It was therefore, paradoxically, the health experts who adopted the reckless strategy that cost so many lives. Only in early 2021 did the government introduce legislation which allowed restrictions to be introduced and the pandemic to be brought gradually under control.

The Covid situation has developed disastrously in Austria and the Netherlands because the governments in both countries failed to maintain public support for the control measures they introduced. The Covid story in Austria began badly with a major outbreak in early March 2020 in the Tyrolean ski-resort of Ischgl, where it is estimated that 6000 people, mostly visitors, contracted the virus in a very short time and were allowed to take it home with them to other parts of Austria and other countries in Europe.

Thereafter, the government was erratic in its application of ‘sticks’ and ‘carrots’, with the consequence that its ‘sermons’ failed to connect with many people. (For instance, Austria has the lowest vaccination rate in this group of nations.) The Dutch government was likewise inconsistent in its application of regulations, and trust in the authorities slumped in January 2021 with the discovery that personal data of people in the contact tracing database had been illegally sold to fraudsters by call centre employees. The day after a curfew was introduced in late January to limit Covid spread, violent protests broke out, described as the worst riots in the country for 40 years.

Thereafter, restrictions were eased as case numbers declined, and were then reintroduced in October when there was a sharp increase in cases. Fresh protests occurred and again turned to violence, especially in Rotterdam, where several hundred rioters, including far-right activists, torched cars and threw rocks at police. The police responded with warning shots and water cannons, and several rioters were shot.

In Austria, when, in mid-November, an alarming rise in case numbers prompted the government to introduce an almost complete lockdown on adults who had not been vaccinated then a brief national lockdown for all, announcing that vaccination would be compulsory from February 1, 2022, tens of thousands (including many far-right supporters) marched in Vienna to protest against these measures. In both countries, protests focused not, as might have been reasonable, against the high death rates, but, on the contrary, against restrictions on personal freedoms!

While Ireland has around half the fatalities per million of population of its close neighbour the UK, its response to the pandemic has also been somewhat inconsistent, and public trust in the authorities was greatly damaged by the fact that the economy suffered so much in the early months.

Denmark (rated number 10 by Bloomberg) has the lowest overall mortality from Covid in Europe (outside of Norway and Finland) and one of the highest vaccination rates. Denmark was among the first European countries to introduce a lockdown in mid-March 2020, and, from May 2020, an effective testing and contact tracing system was introduced.

Vaccination was introduced rapidly, and it has the highest rate of all the countries studied (slightly higher than New Zealand). It seems that the country’s relative overall success has depended on close collaboration between health experts and government, decisive action against the virus, effective subsidies for wages and for businesses, clear communications with the public, strong cross-party cooperation, and the population having a high level of trust in official policymaking.

The parallels with New Zealand are very strong. Particularly striking is the resemblance of the language used by their charismatic, female prime minister Mette Frederiksen, who early on asked Danes to act with a sense of collective responsibility and community spirit (“samfunsssind”) in the face of coming hardships, to Jacinda Ardern’s reference to “the team of five million” and the reminder that we wear masks and vaccinate as much to protect others as ourselves.

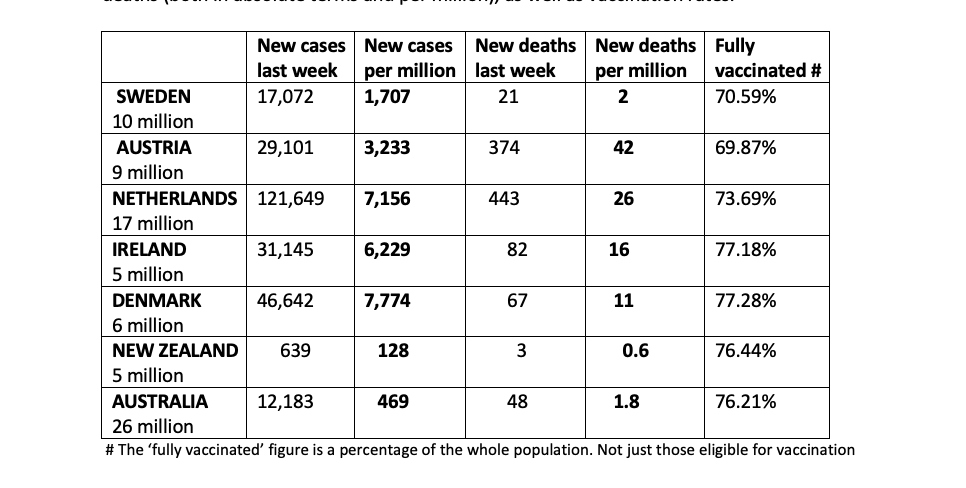

These overall mortality rates do not tell us how each country is handling the current wave of the Delta (and omicron) variants. For that, we need a table showing new cases and new deaths (both in absolute terms and per million), as well as vaccination rates.

There should be no surprise that cases and fatalities remain appallingly high in both Austria and the Netherlands. Really surprising is the reversal of the positions of the two Scandinavian countries: Sweden, the country with the worst overall history, is faring best in dealing with the latest wave of infection and the relatively well-performing Denmark is doing badly – it now has 61 times more new cases and 18 times more new fatalities than New Zealand.

It seems that Sweden’s low population density and the high number of its people who are protected by previous infection, as well as a broad trust in government and willingness to follow regulations once they were introduced, are major factors in their success. By contrast, health authorities in Denmark made the mistake of declaring in September 2021 that, with high vaccination rates and reduced case numbers, Covid was no longer a “socially critical disease”. Restrictions were almost completely removed and the country is now suffering the consequences.

The lessons for New Zealand from these comparisons should be clear. Broadly speaking, we should take great pride in the fact that our Government, working closely with experts in the health ministry, independent epidemiologists and modellers, has developed cautious policies that have protected us to an extraordinary degree against the worst ravages of Covid. The social cohesion we have demonstrated while living and working (or not) under difficult conditions has been remarkable. From the examples of Austria and the Netherlands, we should learn the importance of not allowing the tiny number of people who believe they know better than medical researchers about the nature of the pandemic and about vaccination or those who shout about infringement of their personal freedoms to occupy anything more than the outer edge of our attention. The case of Denmark should offer all the evidence we need that high vaccination rates alone are not enough to protect the population against infection (especially from the Omicron variant) and, more generally, that we must retain limitations on social interaction (and so, infection) in this country as long as is necessary.

The decisions currently facing the New Zealand Government around Covid depend, as they have throughout the pandemic, not just on questions of public health, economics, and politics, but on moral questions. How do we balance the lives of vulnerable people against individual and business freedoms? When Bloomberg ranks New Zealand number 36 among “best places to be during the pandemic”, below Sweden (at number eight), the UK (at number12), and the US – which has the second worst death rate in the world – (at number 13), it is giving clear priority to the latter.

When Christopher Luxon, leader of the National Party, asserts that, in order to protect businesses against further losses, New Zealand should be emerging from social restrictions much faster than the Government is permitting, he is joining Bloomberg in valuing big business over the lives of people at risk of dying of Covid. (He is also ignoring the great measures the Government has provided to cushion small- to medium-sized businesses against damage from lockdowns.) It would be interesting to hear him say just how many more deaths it would be worth to “normalise” the social and economic life of the country, and which country’s record in managing the pandemic he sees as being preferable to New Zealand’s.