Book of the Week: Notably Māori

ReadingRoom

Sally Blundell reviews a unique record of New Zealand life

A dictionary of biographies comes with the dull promise of CVs shuffled into prose, head and shoulder photographs and a wordy riff of what counts as notability (in other words, why people who were left out shouldn’t feel too bad about it). A family history is a single lens story positioning some family members in the limelight, shuffling others off to the wings as soon as is polite.

It is credit to editors Helen Brown and Michael J. Stevens from the Ngāi Tahu Archive Team that Tāngata Ngāi Tahu: People of Ngāi Tahu, the second volume of an ongoing series of books charting the lives of those who descend from Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe and Waitaha (a collective label for all pre-Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Māmoe tribes), cuts a middle path that avoids rote résumés and uses only the broadest grounds for inclusion. The 50 entries in this volume are attentive to genealogical information but also engaging and warm-hearted in their personal detail.

Take the opening sentence of the entry on Joe Karetai: “William Joseph Karetai (Joe) walked tall, walked straight and looked the world right in the eye”. Karetai was a Ngāi Tahu rangitira, an orator, blues guitarist and a fan of Val Doonican – the words are inscribed on his headstone. As a teenager he lost his leg after being hit by a train and spent some years on a farm in Te Urewera. When he returned to Banks Peninsula in the 1950s he set about learning the history of Te Waipounamu, working at the Post Office in Little River, writing unpublished children’s stories, helping run the Rehua boys’ hostel for Māori trade trainees and co-ordinating the South Island branch of the Matua Whāngai Māori foster care programme. He was a hard-hitting man, writes Brown, who loved country music and the All Blacks; a perfectionist with a deep voice and a laugh “like a lion’s roar”.

Or the details in William John Matengaroa (Te Ao Hou) Nutira’s story. Called Ben by his grandmother in honour of London’s Big Ben, he grew up during the Depression years, one of 11 children living near Leeston. Life and sustenance revolved around the harvesting of eels, the gathering of pūhā and watercress, dodging the local ranger to gather swans’ eggs and balancing on the placid back of Donald the horse to reach the unripe apples on a neighbouring farm.

Drawn from family manuscripts, historical narratives, surveyor notebooks, newspaper archives and conversations over what must have been countless cups of tea, these short biographies form part of an evolving tribal family album spreading across Ōtautahi Christchurch, Te Waipounamu and the country. Some are slowed down by opening sentences that try to get essential details – date and place of birth, immediate family – quickly over and done, but once over that speed bump, they tell a vivid story of community and hard graft, of rangatira, community leaders, marae stalwarts, politicians, activists, sportspeople, scholars, fishermen, farmers, shearers, gold-diggers, mutton-birders, gardeners, tug o’ war champs, Housie heroes, teachers, broadcasters, pounamu carvers, weavers, musicians and whole families built around community, faith, sport, mahinga kai and political activism.

Some subjects are well known, such as politician, fashion icon and fencing champion Tini Whetu Marama Tirikatene-Sullivan; soldier, orator, scholar and community leader Ropata Wahawaha Stirling; leader, Te Kerēme claimant and mahinga kai practitioner Henare Rakiihia Tau; and lawyer and rugby legend Thomas Rangiwahia Ellison who scored 43 tries in the New Zealand Native Football Representatives Team’s 1888-89 tour of Great Britain and Australia and went on to write The Art of Rugby Football.

Others less so. In his Foreword to the first volume in 2017, Tā Tipene O’Regan, chair of Te Pae Kōrako, the Ngāi Tahu Archive Advisory Committee, explained the inclusion of hunter and gatherer Tieke (Jack) Pukurākau, who lived alone near the mouth of the Waitaki and died single and childless in 1925. Pukurākau “slipped away and the world moved on,” he wrote, but such people “merit a place in our memory just as much as the more impressive characters who stride through our histories.”

In this book we read the story of Erihāpeti Pātahi, told to gold prospector William Martin in 1863 in a whare on the banks of the Taramakau River on the West Coast. She had two children with sealer, whaler and trader Edwin Palmer and later saved his life when their ship was wrecked en route to Sydney. By 1844 she was estranged from her children; Palmer claimed his “native wife” was dead. After marrying an ex-whaler on Banks Peninsula, she eloped with a former slave of Te Rauparaha to the West Coast where they lived in a small home thatched with kiekie: “She smoked a black pipe, worked the gold claim, fished, gardened and cooked. In the evenings she carved pounamu.” When she finished telling her story, Martin wrote, “Pātahi sat on the floor in silence with her head in her hands.”

Pātahi is one of the 28 mana wāhine featured in this book, a change from the “majority-male cast” of the first book. Work on this volume began in 2018, during the 125th anniversary year of women’s suffrage in New Zealand. The story of the fight for the women’s franchise, writes Brown, is predominately a Pākehā one, “as most wāhine Māori of the 1890s were focused on other matters more pertinent to their people and their survival, including seeking redress for their loss of land and resources.” But the weight given to women in this book is a nod of sorts to that anniversary.

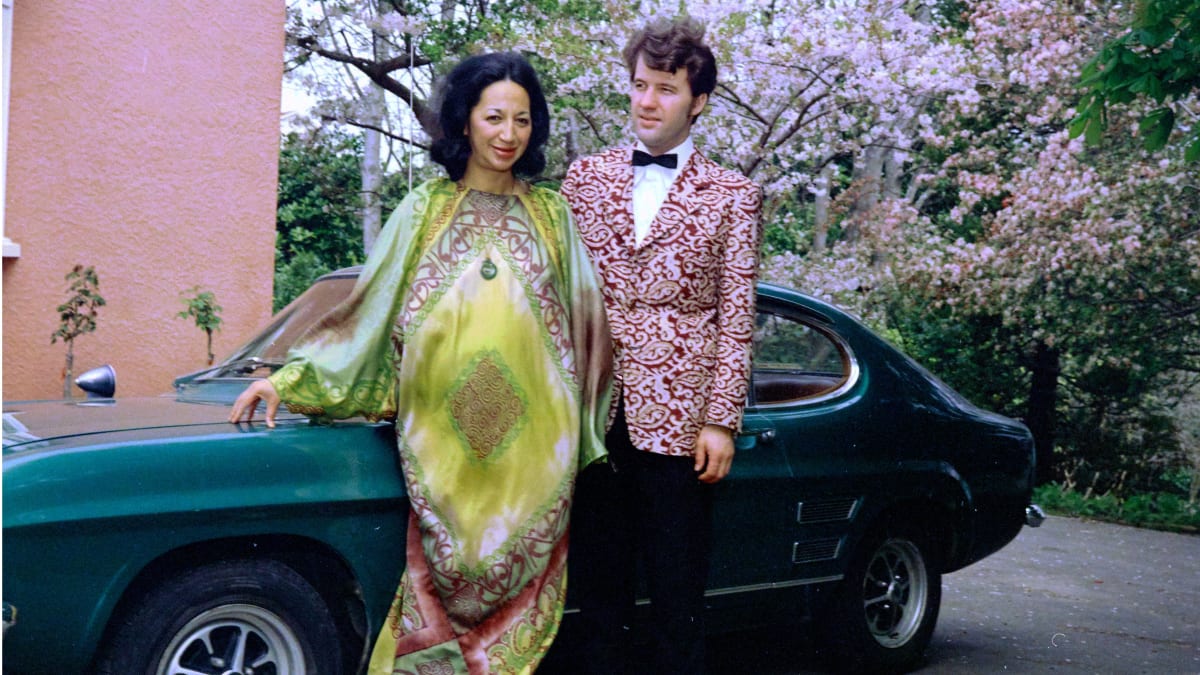

These entries include Airini Ngā Roimata Gopas, an accomplished musician and broadcaster who “paved the way for Māori-medium broadcasting”, here illustrated in a portrait by her husband, respected artist Rudi Gopas.

And master weaver Flora Mei Reiri, named after the daughter of the landlady whose house her parents rented in Dunedin. After moving from Moeraki to a tiny settlement in Wairarapa, she raised eight children, cooked over an outside fire, attended dances to raise funds for local Māori soldiers, played Housie every Thursday (including ‘underground’ competitions in Petone), worked as a supervisor at the Rondo zip factory in Masterton while travelling the country learning, teaching, promoting and exhibiting the art of weaving.

And evangelist, temperance campaigner, activist and soprano soloist Hera Mary Catherine Munro. Munro was a member of the Salvation Army Maori Party that toured Australia to packed houses in the late 1890s; she was one of two women vice-presidents of the new Young Maori Party (YMP); the first women synod member in the Anglican Church in New Zealand; one of the few women whose name appears on the official court record of the Native Land Court in supporting Te Kēreme.

Munro’s story is illustrated by an elaborate Victorian-era photo of the Salvation Army Concert Party, 1898-99. Throughout the book, the use of official photography – uniformed soldiers, wedding portraits, sports clubs, the West Coast axeman’s team competing in Tasmania in 1960, the first general conference of the Maori Women Welfare League in 1951, the third reading of the Ngāi Tahi Claims Settlement Bill – is set alongside more intimate images of people at work – digging potatoes, harvesting tītī, tailing koura, crafting mōkihi (light raft), weaving and entertaining, including a 1914 brochure from the US promoting an exotic show presented by the ‘Raweis’ complete with ‘the peculiar ceremonies, weird music and solemn incantations of the Maoris’.

Put together, the stories and images in this book, interspersed by stunning photography of the islands, harbours and coves of Te Waipounamu, make for a unique and very readable record of community and political life. As a tribal history, its precedents include waiata, whakatauki, the recitation of whakapapa, the carved figures in the dim interiors of the whare whakairo (censored by early missionaries or whisked away to provincial museums) and framed photographs: the front cover of both volumes feature a dozen framed reproductions, evoking the walls of Ngāi Tahu family homes, rūnanga halls and wharenui where photographs of tīpuna, writes Brown, “watch over the activities of their descendants”.

This book version of 200 years of Ngāi Tahu whānui captures that proximity, as if imbued with the clatter of teacups and gentle laughter that prompted these shared stories, making for a comprehensive but warm collection of people and place; a continuum, suggests Brown, of tribal storytelling but also a winning insight into the story of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Tāngata Ngāi Tahu: People of Ngāi Tahu, edited by Helen Brown and Michael J. Stevens (Bridget Williams Books, $49.99) is available in bookstores nationwide.