As fighting continues, a Mariupol survivor rebuilds life in Kyiv | Russia-Ukraine war News

Kyiv, Ukraine – The explosion Ulvi Zulfili witnessed in the southern Ukrainian city of Mariupol made him stutter for days.

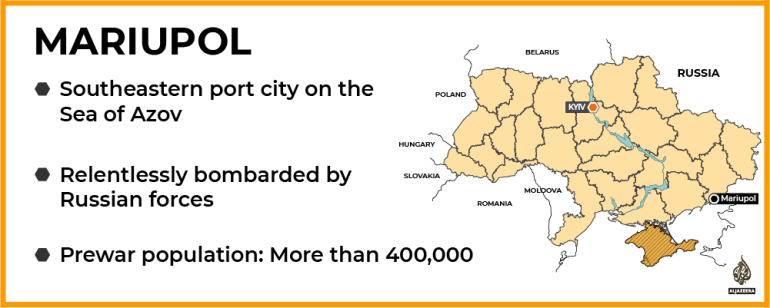

In mid-March, hundreds of civilians, including children, thronged the basement of Mariupol’s drama theatre, hiding from incessant Russian shelling that was killing hundreds of people a day.

Even though two signs saying “children” had been drawn in metres-long letters near the theatre, a Russian fighter jet bombed it on March 16.

As many as 600 people were killed, according to Ukrainian officials and media reports. Russia denied carrying out the attack, saying Kyiv staged it from within the building.

On that gloomy, cold morning, Zulfili biked to downtown Mariupol to look for formula for his friend’s newborn son, whose stressed-out mother was unable to produce breast milk.

He saw how the white theatre with marble columns was hit by a cruise missile. A mushroom of smoke and dust rose up twice as high as the nearby supermarket.

He was transfixed by horror – and could not hear a sound.

“The strangest moment was when you see a picture but don’t hear it,” the 26-year-old told Al Jazeera. “You can’t understand whether you’re alive or not.”

“In a moment, the sound reaches you with the blast wave. It almost rips the clothes off you. And you understand that you are alive and need to run away,” he said in a cafeteria, now safe and sound in Kyiv.

Days after Al Jazeera interviewed him mid-December, Mariupol’s Moscow-installed authorities razed what remained of the theatre.

Out of the frying pan

Zulfili’s stutter is now gone, but so is the life he lived in Mariupol.

He arrived there from Azerbaijan at age four and can still recall moments of his early childhood – “riding a horsie” and seeing oil derricks that made his South Caucasus homeland one of the world’s oldest oil producers.

But his father, Elshad, did not want his son to grow up and die in the war that scarred Azerbaijan.

In the early 1990s, a conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian-dominated enclave in Azerbaijan, became the first open war between two former Soviet republics.

Russia declared itself Armenia’s “protector” and brokered a truce in 1994. But almost yearly border fighting kept interrupting one of the ex-USSR’s “frozen conflicts”.

Elshad Zulfili opened a grocery store in Mariupol, a city of 500,000 people that seemed like a tranquil backwater west of the Russian border.

The Azov Sea port was dominated by two mammoth steel factories, which employed tens of thousands of people and filled the city with smoke.

The factories were the jewels in the crown of Rinat Akhmetov, one of Ukraine’s richest men and the main backer of the pro-Moscow Party of Regions, which dominated politics in Ukraine’s Russian-speaking east and south.

In winter, dust from coal-loaded cargo ships in the port turned snow black. But summers were long and warm, and people filled the beaches and splashed in the shallow, barely salty water.

The Zulfilis lived in a five-bedroom house in the Sailors’ Settlement, a suburban neighbourhood in transition, where posh mansions stood next to old huts.

Elshad died of a heart attack in 2005 in his shop, and Ulvi eventually became the breadwinner of the family.

Remaking a city

Trouble began in 2014.

Months-long protests in Kyiv toppled President Viktor Yanukovych, who headed the Party of Regions but was widely seen as oligarch Akhmetov’s political puppet.

In response, Moscow annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and sparked a separatist uprising in its eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk.

Mariupol was roiled by anti-Kyiv rallies, and separatists backed by Russian fighters invaded it in April.

But by June, steelworkers and Ukrainian servicemen kicked them out, and Mariupol became the de facto capital of the Kyiv-controlled part of Donetsk.

Its new mayor, Vadym Boychenko, began to patch up and spruce up the city. Potholed roads were fixed, buses and trolleys were brand new, and Mariupol’s image began to change.

“His goal was to show the other side that the Ukrainian-controlled territory is better,” Zulfili said.

The city was a pocket of peace just a couple dozen kilometres from the front line.

Plenty of jobs and cheap housing attracted people fleeing the rebel-controlled side.

One of them was Diana Berg, who organised pro-Ukrainian rallies and was sentenced to death in what Russia-backed separatists declared the People’s Republic of Donetsk.

In Mariupol, she founded Tuy, an “art platform” for exhibitions, concerts and film screenings.

“It seems strange in a city near the front line,” she told Al Jazeera. “But you can’t live just thinking about war, war, war and feeling depressed.”

Meanwhile, Zulfili kept his father’s grocery store and eventually bought an automobile repair shop and seven cars to lease to cab drivers. He also spent hours in his garage restoring vintage vehicles.

The increasingly authoritarian People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk filled the city with news about torture chambers and economic degradation, but many in Mariupol remained pro-Russian and opposed to Kyiv’s policies to promote the Ukrainian language and state symbols.

“If you don’t like the language people speak or the books they read, you’re an invader,” Vasily Pilipchuk, a salesclerk in Mariupol, told Al Jazeera in 2019.

Into the fire

Before dawn on February 24 last year, Zulfili’s girlfriend woke him up, saying the war had begun.

He told her she was dreaming and went back to sleep – only to be woken up by an explosion that shook the house and threw him out of bed.

Within days, the shelling was happening like clockwork – from 8am to 5pm.

Every five to seven minutes, a bomber would take off from the Russian city of Rostov less than 200km (124 miles) east of Mariupol.

Each plane would launch two missiles, and everyone in Mariupol learned to run to their cellars or bomb shelters and calculate their distance from the explosions.

Everyone also knew that razor-sharp bomb fragments would fly around for at least 40 seconds after each blast.

Every sunset brought relief from the planes, but at 6pm, curfew began as darkness fell on a city with no electricity or running water.

Zulfili’s neighbourhood was targeted and damaged far less than the apartment buildings in central Mariupol, but his family still chose to sleep in their ice-cold basement and began every morning by making a fire, boiling water and making tea in a samovar.

Zulfili always got some of it to an elderly neighbour who could barely walk after surgery.

War brought all their neighbours together as they helped one another with water, food and firewood.

Zulfili would drive to springs by the sea, and each neighbour would put their plastic bottles and canisters in the boot of his car to fill up.

As Russian and separatist soldiers were closing in on the city, people began to leave. They made it out when the warring sides could agree on the timing of humanitarian corridors for civilians.

All city residents received text messages with a corridor’s route and timing, but the Russians kept shelling the cars and buses or stopped them and kept them in hours or even days-long lines.

Mariupol’s once-perfect roads were now studded with landmines and potholes, but Zulfili kept driving around slowly and cautiously.

Once, he and his friend saved a young woman badly wounded in the face, limbs, stomach and groin by shelling.

“She was really hurting,” he said. “We kinda wanted to get her [to the hospital] as fast as we could, but you need to adjust the speed because the roads are horrible and she was in pain.”

They dropped her off at a hospital – and barely escaped a cruise missile that shook the car, he said.

The woman survived.

The escape

After fleeing the theatre attack on March 16, Zulfili biked straight to his friend whose son needed baby food – only to barely survive another bombing that killed a pregnant woman’s husband.

A Red Cross team picked her up and helped deliver the baby without telling her that her husband was dead, he said.

Then Zulfili’s family decided to leave.

His mother and girlfriend, her mother, his neighbour’s family and countless suitcases and bags filled his biggest car, a black Kia.

“We were taking anything of value,” he said.

He gave another car to his friend, a former serviceman who only spoke Ukrainian and thought he would be detained and killed as he tried to leave the city.

“I was more concerned about him than about myself,” Zulfili recalled.

Luckily, he managed to escape.

Zulfili also gave away his other cars – except for one that was blown to pieces by shelling. No people were hurt, he said.

It took his family and neighbours two days of driving, stopping, waiting at checkpoints and driving again to get to a Kyiv-controlled area.

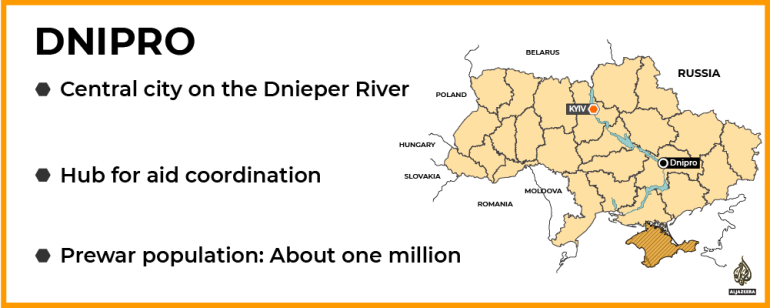

They settled in the city of Dnipro, but after several months, they decided to move to Kyiv.

Finding a place to live proved difficult, but after paying a sizeable deposit, they moved into an apartment in a northern Kyiv suburb. It is not far from Bucha, where Russian soldiers killed hundreds of civilians in February and March, according to survivors, witnesses and officials.

Zulfilli’s girlfriend went to Germany for the winter, and he lives with his 56-year-old mother, Irade, who is torn by homesickness, boredom and a desire to contribute financially.

“Mum is psyching out because she can’t find a job, because she can’t help somehow,” he said.

Irade began helping fellow Azeris at a grocery shop they have opened while Zulfilli works as a cabbie driving the black Kia that saved their lives.

Because of Russian strikes on key infrastructure, blackouts occur almost daily, and Kyiv feels chaotic and cold.

The family finds it hard to live in a tiny apartment after years in a spacious house, especially with drone and cruise missile attacks going on. Government benefits are meagre, and Zulfili has to work hard to pay the rent, utilities and his debts.

“We’ll wait out the winter, my girlfriend will come back, and we’ll start thinking, either start putting aside more [money] or thinking about a mortgage,” he said.

“But when you think about paying it off for 30 years, you are like, will you survive that long?”

The family has another plan, though. Their house in Mariupol was windowless but otherwise intact until new tenants moved in November.

They had fled Donetsk because of the conscription of men who are being herded to the front line, Zulfili said.

“We said [to the tenants]: Fix [the windows and heating], live there for a year on the condition that when we come back, you will find another place to live,” he said.