Traditional Knowledge Buttresses Iwi Holdings Against Rising Waters

Māori issues

With investments in tourism and primary production, iwi are hit by the Covid downturn and the cost of climate change mitigation – but they believe the longer view they take on protecting taonga places them in a safer position than many investors

Manaaki Nepia grew up eeling in the murky waters flowing into the Waikato River, beneath the shadow of the Huntly coal power station.

She wouldn’t take the freshwater tuna from there today; years more of industrial and agricultural run-off further upstream have further polluted the river.

As an iwi, they will often bring together a group to paddle waka from the small Waikato Iti stream coming off Tongariro, down into the river and 400km to the sea. “Paddling all the way down, we see the variation in the colour and it’s enormous,” she says. “By the time you get to Karapiro, the discolouration is almost unbelievable. Is this the same river?”

It is seeing the waters of her awa grow more and more yellow that drives her to mitigate the damage being done to the environment, in her role as strategy manager for Waikato-Tainui – even if that means placing a rahui on taking freshwater tuna and whitebait, cutting the livestock on the iwi’s beef farms, or second-guessing their partnership to build an affordable housing estate on the flood plains of the north Waikato.

The challenge is similar further north for Paul Knight, chief executive of Ngāpuhi Asset Holding Company. As it hosts Treaty of Waitangi commemorations today, the country’s biggest iwi still hasn’t resolved its mandate sufficiently to negotiate its Treaty settlement, so unlike other iwi with their land holdings, up to 70 percent of Ngāpuhi’s revenues come from fisheries.

Should iwi work to grow their putea even if it means diversifying out of traditional sectors? Click here to comment.

Ngāpuhi holds more deepwater hoki fishing quota than anyone else but, last year, Knight pushed successfully for voluntary reductions to the allowable hoki take, to manage the fishery. That meant a cut to the revenues reported by the iwi last year, but he insists it’s worth it in the long term.

“We work across traditional, recreational and commercial fisheries inshore – but in the deep water hoki fishery, there are really only commercial interests,” he says. “So it should be less complex. If we can’t get that right, we don’t have much authority to talk about inshore fisheries like snapper.”

Iwi are required to take a longer view of how they manage their assets; that’s because they are investing not just for financial return but for social and environmental return. They are required to preserve their taonga for future generations.

Their investment in those local taonga – forests, farms, fisheries and tourism – has made them vulnerable to shocks like the Covid-19 slowdown and border closures. It also makes them even more exposed to the costs of climate change mitigation.

But they believe their longer view – forged by the obligation to develop their resources for the benefit of future generations – provides a model for other investors.

Compare the three-to-five year horizon of many private equity fund investments with the 500-year sustainability strategy of an iwi-owned investment company like the $350 million Wakatū Incorporation, at the top of the South Island.

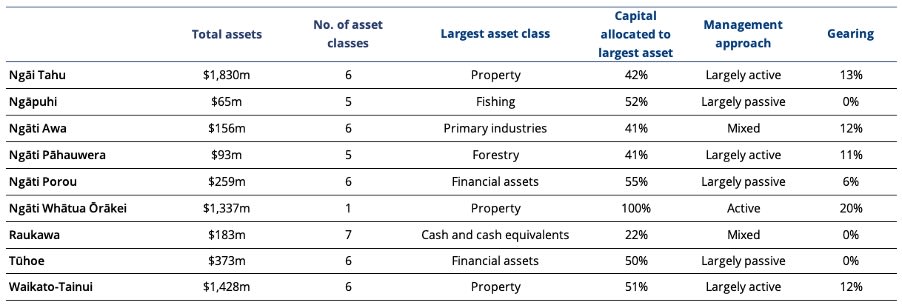

A TDB Advisory report, published today, assesses the performance of nine of the country’s biggest iwi, including Tainui and Ngāpuhi. It finds their performance has been “sub-optimal”, in large part because they refuse to diversify their asset bases far beyond their own rohe.

“Many iwi hold a large portion of their assets in property within their rohe. While there are often strong cultural and historical reasons for this, in principle these iwi could reduce their exposure to risk without reducing their expected returns, by expanding the geographic boundaries of their investments.”

But Paul Knight argues that iwi are better to stay in the sectors they know, and often have known for generations, and to work within those sectors to influence change. That won’t always return the biggest financial dividend, in the short term.

The challenges around climate change are even bigger than those around fisheries sustainability. Already the Ngāpuhi iwi-owned company is investing in solar power and, just this week, it announced it would be opening a hydroponic berry farm near Kaikohe, in a commercial estate backed by $19.5m of Provincial Development Unit money.

“It’s a question of how soon and how quickly we reduce our footprint in relation to others,” Knight said. “We’re the owner of a Mobil service station in Kaikohe, so yes, we’re following the discussion around Climate Change Commission draft report very closely. That’s just one of our investments that’s affected.

“My personal view is that to have the best knowledge of an industry like fisheries, you have to be involved in it. It’s better to be onboard influencing change, than on the outside casting stones. So I wouldn’t suggest Ngāpuhi move away from fisheries.”

Manaaki Nepia believes they have taken the learning of generations, and are applying them to emerging challenges like the the climate crisis.

She points to some of the iwi’s lower-lying marae, on the coast at Kawhia, Aotea, Raglan, Port Waikato and the lower reaches of the Waikato River. There are some that have generations-old stone pillars that were built for when the floods come, to place a deceased body on so it could lie in state safely above the waters. Those same marae have ways of measuring the rising waters so as to make their flood preparations.

Now the kuia and kaumatua feel better able to advise and prepare their marae for the ever more frequent floods expected with the warming climate. And the iwi has set aside a seven-figure sum, alongside public money, to begin the work on flood protections for those 20 marae. One is the Maketu Marae at Kawhia, where the Tainui waka is famously said to have come ashore, hundreds of years ago.

At high tide the waters of the Kawhia Harbour already lap at the banks of the marae, not far below the foundations of the wharenui. For some marae, that will mean relocating them to higher ground.

“When you talk to therm, flooding is not a new thing, though in the past it may have been only once every 100 years. It’s not new for them. Some were rebuilding their wharekai, some have water storage issues, some have food production areas especially around Pokeno and Tuakau, so we’re discussing what we need to do to keep our marae safe from a climate change perspective.”