Drug Lord, Pablo Escobar’s Hitman Who Killed 3000 People Dies Of Cancer At 57 (Photos)

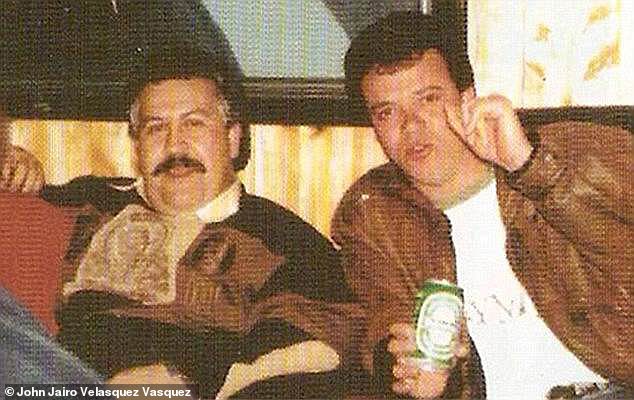

Drug lord Pablo Escobar’s (left) with his former chief hitman Jhon Jairo ‘Popeye’ Velasquez

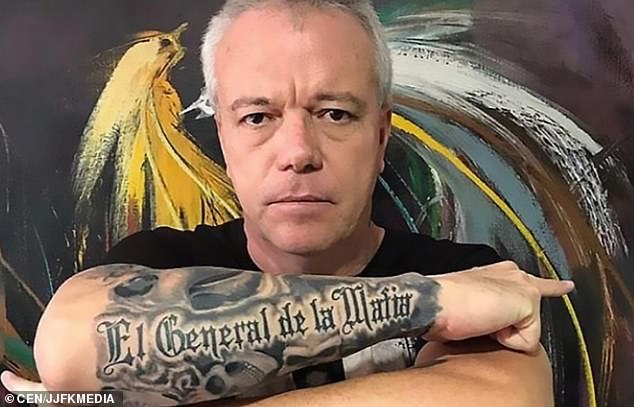

Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar’s former chief hitman Jhon Jairo ‘Popeye’ Velasquez has died of cancer today at the age of 57.

Velasquez served a life sentence after admitting to killing 300 people and ordering the deaths of 3,000 more as he violently enforced Escobar’s legendary reign of terror.

The heartless assassin – who once described killing as ‘like a day at the office’ – was jailed in 1993 – the year Escobar was gunned down by police in his home town of Medellin – but was released in 2014.

Velasquez then went into hiding for several years fearing reprisals from his victim’s families and members of the Medellin Cartel he helped to convict in return for a lighter sentence. He was arrested again in May 2018 on suspicion of extortion and conspiracy and had been back behind bars since then.

Colombia’s National Penitentiary and Prison Institute (INPEC) confirmed that Velasquez died in the early hours of the morning in the National Cancer Institute in the capital Bogota.

He had been diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus which had spread to his lungs, liver and other organs and had been hospitalised since December 31.

The killer had been held at the maximum-security Valledupar prison in the northern Colombian department of Cesar.

Velasquez was the leader of the hitmen of the Medellin Cartel run by Escobar until his death in 1993 when he was shot dead on a roof top in his home town in Colombia by a specialist police unit.

Escobar had previously been found guilty of terrorism, drug trafficking and murder and served time behind bars before escaping and going on the run.

Velasquez helped plan the homicide of former presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galan, who was shot to death in 1989, and the bombing of Avianca Flight 203 which killed 107 people in 1989.

He referred to himself as ‘Pablo Escobar’s trusted assassin’ but tried to paint himself as a reformed character after his release from prison in 2014.

He said: ‘I’m also a victim of Don Pablo. I was not responsible for the assassinations. I was a professional killer and nowadays I have reconsidered it. I am a repented and reformed man.’

As Escobar’s head hitman, ‘Popeye’ executed – either personally or on his orders – thousands of people deemed to be a threat to his cocaine trafficking empire, including policemen, journalists, politicians and judges, while innocent civilians were also inevitably caught up in the carnage.

After meeting Escobar through a childhood friend when he was 18, Vasquez’s first ‘contract’ was to kill a bus conductor in Medellin who had enraged Escobar after he didn’t help a friend’s mother who fell as she got off the bus and died.

The cold-hearted killer, who was paid £25,000 for the hit, later said: ‘I made some enquiries, found the guy and killed him. I felt nothing. That idea that a person cannot sleep for thinking about dead people doesn’t apply to me.

‘Neither did I need to take drugs, or smoke, or take pills to calm myself down. The deeds that I have done don’t deprive me of sleep.’

In an interview from a mountain hideout in 2015 – where he was in fear of his life from relatives of his many victims – he insisted all those he killed were just ‘casualties of war’.

He said Escobar – once ranked by Forbes magazine as the world’s seventh-richest man – was far more powerful than anyone had imagined before he was finally gunned down by US DEA agents after a rooftop showdown in 1993.

As well as hundreds of other murders, ‘Popeye’ achieved notoriety for a string of attacks on well-known members of the Colombian government.

He kidnapped and tortured a future Colombian president and vice-presidents, he killed an Attorney General, and helped plot the murder of Colombian presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galan, the only murder out of thousands for which he was actually convicted.

By the time he was arrested in 1992, he had killed 250 people with his own hands – including his own girlfriend – detonated over 250 car bombs, and was linked to the 1989 bombing of an Avianca jet, which killed 107 people, just to assassinate one traveller, another presidential candidate.

In December he told from behind bars how the cartel smuggled the bomb onboard in the briefcase of an unsuspecting young man who thought he was merely recording some DEA agent’s conversations on board.

As he opened the briefcase the bomb detonated.

He told the Daily Beast from inside prison: ‘That briefcase was a work of art.’

But despite having taken so many lives, Vasquez claims he had no choice but to obey Escobar’s orders and feels no guilt for the crimes.

He said in the 2015 interview: ‘I’m also a victim of Escobar. I was not responsible for the assassinations.’

Of the plane bombing, Vasquez admitted: ‘I took part, but Pablo Escobar planned it.

‘I handed over the money to plant the bomb, but I’ve already paid for that.’

The atrocity failed to kill its target after presidential candidate Cesar Gaviria changed his travel plans at the last minute.

Vasquez claimed the attack, and many others, was only possible because Colombia’s intelligence agency the DAS – provided security to state institutions, politicians and other figures – was under Escobar’s control.

He said: ‘Without the involvement of DAS in the 1980s the murders of many politicians, as well as drug traffickers who were enemies of the Medellin Cartel, would not have happened.’

At its peak, the Medellin Cartel supplied 80 per cent of the worldwide cocaine market and generated at least $420million (£270million) in weekly revenue.

Escobar’s brother once revealed the organisation was making so much cash that they used to spend £1,200 a month on rubber bands just to hold it in bundles.

At Escobar’s palatial estate, the drug lord lived an extravagant lifestyle.

As well as a private zoo, including a herd of 50 hippos imported from Africa, he also flew in beauty queens and famous musicians for entertainment and would reportedly sent helicopters to pick up his favourite hamburgers.

But outside, his ruthless cocaine monopoly turned his home city Medellin into a war zone and made Colombia the murder capital of the world, as the gang mercilessly killed anyone who tried to stop him.

Velasquez was the cartel’s ‘head of operations’ and plotted most of its high-profile slayings, often in public places and with no concern for the lives of innocent passers-by.

The group’s message to those in power was ‘plata o plomo’ – silver or lead – which colloquially translates to ‘take the bribe or end up dead’ .

When, in 1991, Escobar gave himself up after being linked to the assassination of a presidential candidate, authorities granted his wishes not to be extradited to the US and even let him build his own ‘prison’ on the outskirts of Medellin named La Catedral, complete with a football field, waterfall, Jacuzzi and dolls’ house.

His loyal hitman went with him and continued to murder on his behalf as he ran his drugs empire behind bars.

When the under-pressure government announced plans to move Escobar to a tougher jail, the drug lord simply walked out of the back gate and vanished.

In fact it was Escobar’s failed assassination of Cesar Gaviria in the aeroplane explosion which proved to be the drug lord’s undoing.

The presidential candidate went on to win the 1990 election and proceeded to launch an anti-drug crusade, which Escobar answered with a bloody war on the government that ended when the kingpin was killed in a rooftop gunfight with police in Medellin three years later.

In October 1992, with the noose tightening around Escobar, ‘Popeye’ handed himself in and confessed to his 3,000-plus body count.

In jail, he cooperated with the authorities to secure the conviction of other Medellin members, studied for degrees and acted as a mentor for younger prisoners, encouraging them not to return to a life of crime on their release.

After 22 years behind bars, Vasquez walked free in August 2014, escorted by 200 police in five vans and on 10 motorbikes. At the time he thought there was ‘an 80 per cent chance of me being killed. Twenty per cent chance of making it.’