Wise Business Leaders Invest in Society, Not Short-Term Financial Returns

Business

Corporates are potent players in our democratic politics and responsible global decision-making, writes Rod Oram, but their response so far is rhetoric, not reform.

‘Corporate political responsibility’ is a new and growing demand on business in some countries. It’s a call for companies and their leaders to play constructive roles in helping their nations solve their greatest challenges, such as climate, inequality, distrust, division and racism.

In simpler times, the minimum expectation on business was to operate within the letter, and hopefully the spirit, of the law. When change was needed, society found businesses were only keen on actions that suited them, or they could adjust to quite quickly.

But these days our challenges are far more complex, multi-faceted and long-term. Only whole-of-society responses will solve them. Covid is one obvious example, the climate crisis another. The first shows we can do it. The second shows us how badly we usually fail.

Taking political responsibility means companies will have to advocate for actions that pay off far beyond their short corporate investment horizons. And/or the benefits accrue to society rather than directly to the business owners. Wise ones, though, understand they can only thrive if society thrives.

In recent weeks, a flurry of senior executives and organisations speaking for them have declared their commitment to corporate political responsibility. Three examples are:

► Larry Fink, the chief executive of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, said that investors who focus on the interests of wider society reap greater rewards.

“Stakeholder capitalism is not about politics,” he said in the letter, entitled The Power of Capitalism, which he wrote to chief executives of BlackRock’s investee companies. “It is not a social or ideological agenda. It is not ‘woke’. It is capitalism, driven by mutually beneficial relationships between you and the employees, customers, suppliers and communities your company relies on to prosper.”

He particularly emphasised the limits on how much companies can do to respond to the climate crisis. “Businesses can’t do this alone. We need governments to provide clear pathways and a consistent taxonomy for sustainability policy, regulation, and disclosure across markets.”

► In the UK, some 200 companies have condemned a parliamentary bill that would impose harsh new restrictions on public demonstrations. Similarly in the US last year Amazon and General Motors were among major corporates that spoke out against “discriminatory” voting laws proposed by Republican lawmakers.

Such actions are still rare but with worries about civil liberties and democratic integrity rising in many countries, the calls for companies to declare where they stand will grow. “It will increasingly be a ‘which side are you on?’ moment,” says Aron Cramer, head of BSR, a UK sustainability consultancy. “Businesses will be expected to weigh in — and a lot of CEOs and boards are uncomfortable doing that.”

► The World Economic Forum’s Davos meeting this past week – online only this year because of the pandemic – had several sessions exploring the theme. Such as, Renewing a Global Social Contract and Environmental, Social and Governance Metrics for a Sustainable Future. The Forum also has an ongoing workstream on stakeholder capitalism in conjunction with the International Business Council.

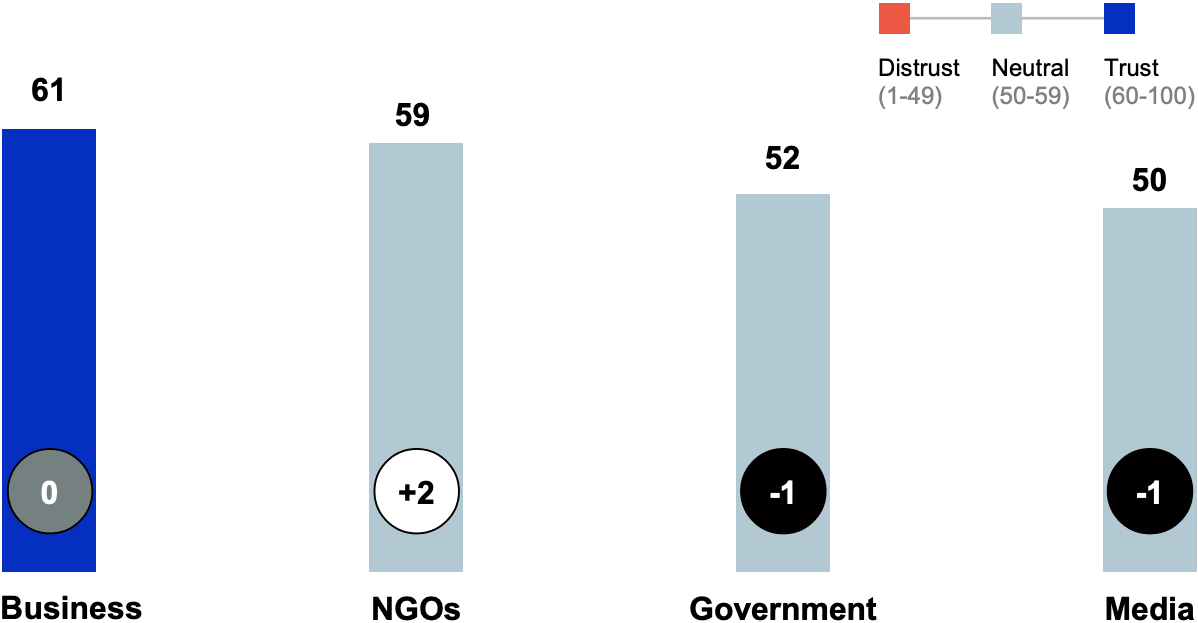

The Forum also highlighted the latest edition of the global trust barometer compiled by Edelman, the world’s largest PR firm. Its polling of 36,000 people in 27 countries (which didn’t include New Zealand) showed that businesses were the only institutions people trusted (by its definition; see the chart below). This was a marked change from its 2020 polling.

Business only trusted institution (%)

From this and other findings in the survey, Edelman concluded that “societal leadership is now a core function of business”. In particular, chief executives are expected to shape conversation and policy on jobs and the economy (76 percent), wage inequity (73 percent), technology and automation (74 percent) and global warming and climate change (68 percent).

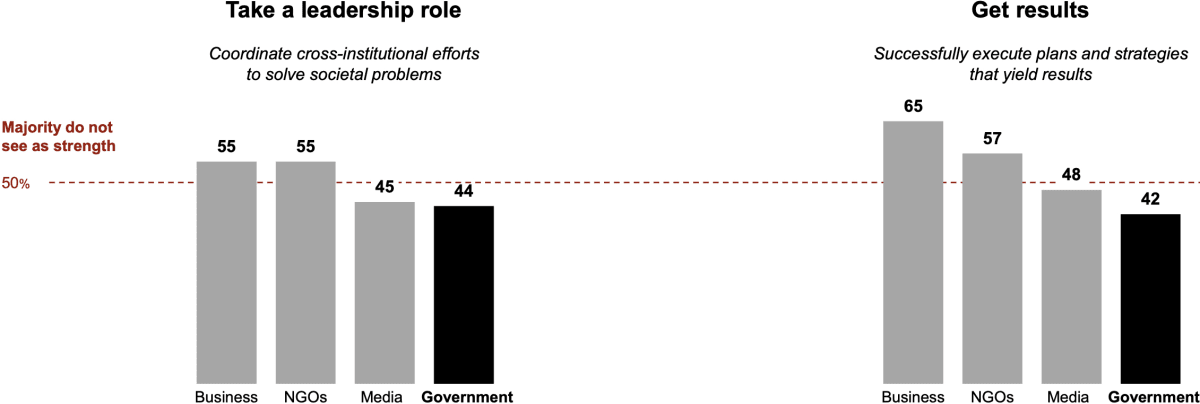

Moreover, governments “are not seen as able to solve societal problems”.

Government not seen as able to solve societal problems

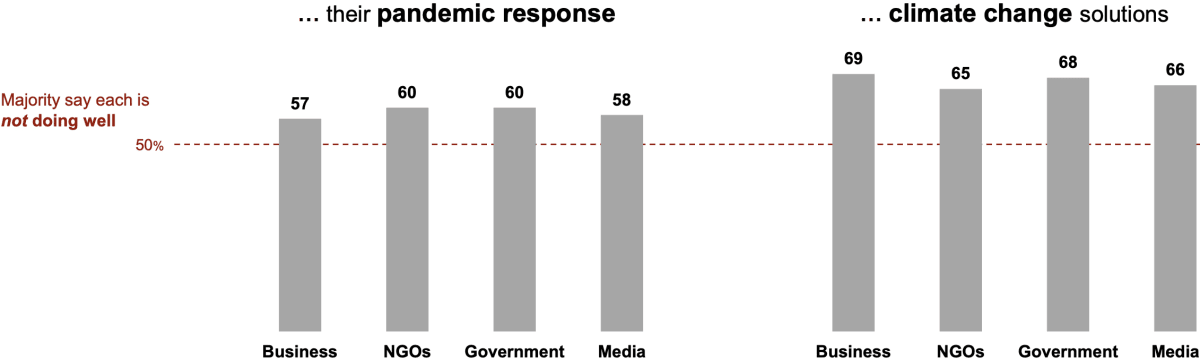

However, when it comes to existential challenges such as the pandemic and the climate crisis, business scores just as poorly as government, NGOs and media in Edelman’s quartet of institutions.

Institutions failing to address institutional challenges

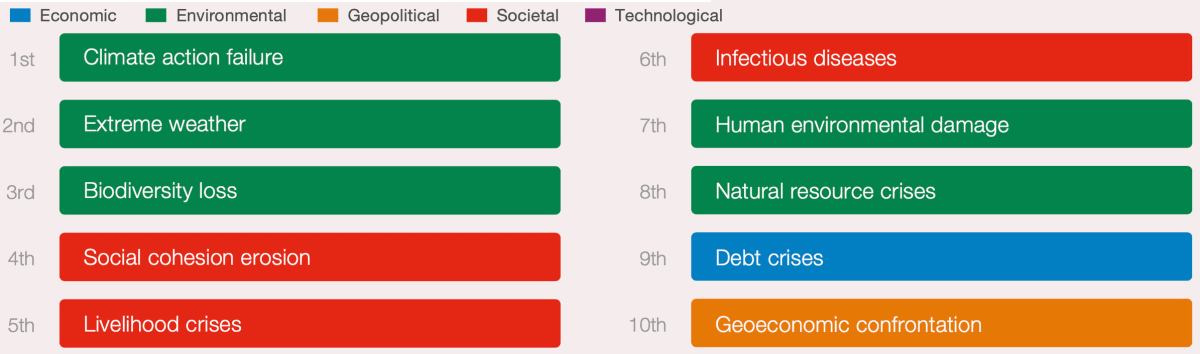

This conclusion is the most worrying of all because existential risks account for nine of the top 10 global risks for the next decade, according to the 2022 edition of the Forum’s Global Risks Report. The only purely economic/business risk is a potential debt crisis at number nine.

‘The most severe risks on a global scale over the next 10 years’

Yet, if business leaders really are serious about corporate political responsibility, they must also own up to their roles in creating, and solving, crises of climate, biodiversity loss, social cohesion, livelihood, human environment damage, natural resources, and geoeconomic confrontation.

As Martin Wolf, the Financial Times’ chief economics columnist, wrote in his column this week: “We in the western world confront two crises: a collapse in trust in our democratic political system and a planetary environmental threat. The former requires the renewal of common purpose at home. The latter requires not just common purpose at home but shared global purpose. These are things business cannot provide. It will take effective politics, instead. A big question is whether business will be able to promote the needed political solutions or just create political problems.”

He concluded, though, that business and capitalism as we currently practise them are a major part of the problem, and not the solution.

“Businesses operate within a system: market capitalism. This system is now globally dominant, at least in the economic domain. That is true even in today’s China. The essence of capitalism is competition. That has profound implications: competitive profit-seeking entities are essentially amoral, even if they are law-abiding. They will not readily do things that are unprofitable, however socially desirable, or refuse to do things that are profitable, however socially undesirable.”

Wolf is a distinguished economist on a long and fruitful intellectual journey. Back in the late 1980s, he was a neo-liberal much admired, for example, by Roger Kerr and colleagues at the NZ Business Roundtable.

But by the time Kerr invited him here to deliver the 2004 Trotter Lecture, Wolf was already articulating a more sophisticated and balanced view of capitalism, globalisation and the role of government. At the gala dinner, as I recall, Kerr seemed pained by Wolf’s words as he delivered his lecture.

In his latest column, Wolf explores why business remains ill-equipped to deal with existential crisis and how society and governments can remedy that. He draws in part on a collection of papers on the subject which constitute the latest edition of the Oxford Review of Economic Policy.

Particularly important are essays by Anat Admati of Stanford and Martin Hellwig of the Max Planck Institute. “Both consider the role of business leaders as influential but self-interested voices in setting public policy in company law, competition law, taxation, financial regulation, environmental regulation and many other areas. The outcome, they and other authors suggest, has been the emergence of a system of opportunistic rent extraction that creates uninsurable risks for the majority and vast rewards for a few. This has in turn played a big role in undermining confidence in democracy and increasing support for populists.”

However, “the pandemic has created an opportunity for a politics of competence and shared purpose. This gives us at least a chance to do better. I believe there is a case for substantial reform of our form of capitalism, while preserving its essence of innovation and competition. This would not be unprecedented. The creation of the joint stock limited liability company was once a highly controversial innovation. So was the creation of social insurance. Today, however, the biggest issue, in my view, is the relationship among business, society and politics.”

Wolf outlines how to improve that relationship. But he concedes that the response so far from business is rhetoric, not reform.

“The pandemic has brought many lessons. But perhaps the most important is what can be done if the skills of private business are united with public resources to achieve urgent purposes. That is what makes the vaccine story so heartening (and the anti-vaxxer reaction so depressing),” he says.

“Business leaders are rational people in charge of important institutions. They have to appreciate the need to strengthen our capacity to make collective decisions sensibly. Like it or not, they are potent players in our fragile democratic politics and so also in global decision-making. They need to take this role seriously and play it decently and responsibly. For all the rhetoric we hear, this is not yet what we see.”