Why tackling the global industry of fake Indigenous art is like playing ‘whack-a-mole’

Unreserved44:03Copycats and copyrights of Indigenous art

You’ve probably seen Andy Everson’s work – without even knowing it.

The K’ómoks and Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw artist is the creative mind behind a popular Every Child Matters logo that’s on orange T-shirts across the country.

“The Every Child Matters [image] is near and dear to my heart … having ancestors and relatives that went to residential schools. So I made this image available for people to use … and also for the Orange Shirt Society to be able to produce official shirts,” Everson told Unreserved host Rosanna Deerchild.

Everson had one stipulation for those using the image: that proceeds from selling items with it go back to Indigenous non-profit organizations.

But after the revelations of suspected unmarked burials at the site of a former residential school in British Columbia, demand for orange shirts and Every Child Matters paraphernalia skyrocketed.

“People started to put [the image] on everything and selling it all over the place,” Everson said. Many of these sales — some of them by online businesses located overseas — were not going back to Indigenous organizations, he noted.

His experience with the Every Child Matters image is just one example of the way non-Indigenous people and businesses profit from Indigenous artists’ work.

Everson said he didn’t have the time or resources to pursue legal action. So there wasn’t much he could do to stop businesses from profiting from his work and the outpouring of support for Orange Shirt Day and the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

A global industry of fake Indigenous art has made it harder for Indigenous artists to make ends meet doing their work. To Indigenous artists, it’s also cultural theft.

The industry ranges from designs copied onto apparel and home decor to carved masks and totem poles, reproduced in Asia and Eastern Europe and sold cheaply. The industry of fake Indigenous art also includes massive fraudulent art rings.

While the problem of copycat Indigenous art has been going on for many years, Indigenous and non-Indigenous people are pushing for legislative changes to protect artists’ work, and to ensure profits go back to the artists and their communities.

‘Art fraud is big’

Sen. Patricia Bovey, the first art historian to sit in the Canadian Senate, estimates that the industry of fraudulent art costs Indigenous artists millions of dollars.

“Art fraud is big. It comes right after issues of the illicit drug trade and firearms,” Bovey said.

It’s important that Indigenous artists are compensated for their work, she said, adding that art collectors and consumers should get what they pay for.

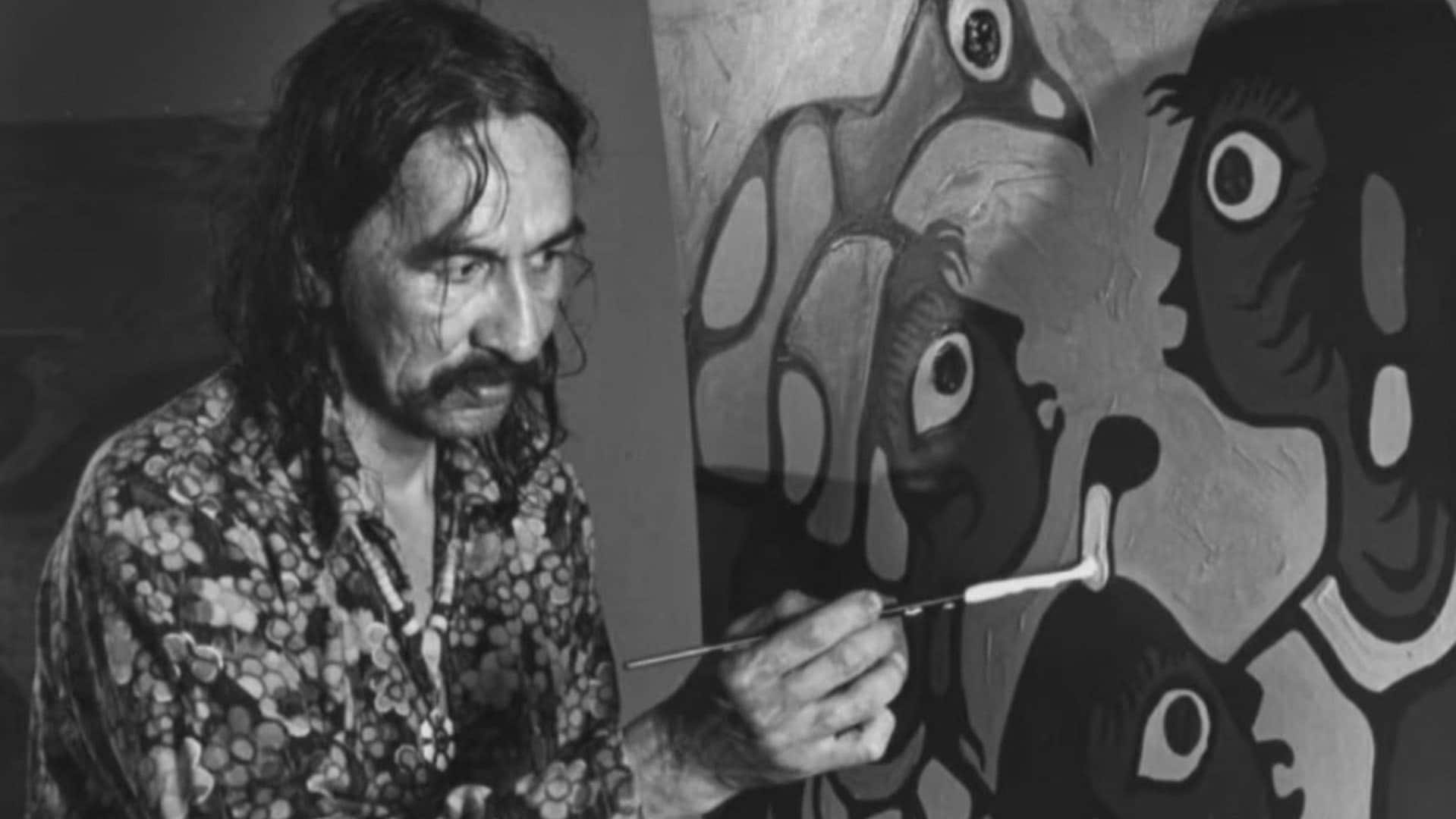

On March 3, Thunder Bay police and the Ontario Provincial Police announced eight arrests following an investigation into a ring of fake Norval Morrisseau artwork. Over 1,000 paintings had sold for tens of thousands of dollars to “unsuspecting members of the public,” according to police.

Morrisseau, the famed Anishinaabe artist who popularized vivid and colourful Woodland style art, died in 2007.

WATCH | Arrests following investigation into Norval Morrisseau forgeries:

More than 1,000 paintings were seized and eight people face a total of 40 charges resulting from a years-long police investigation into the forgery of artwork by Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau.

Bovey was working at the Winnipeg Art Gallery when Morriseau and other Indigenous artists founded the Indian Group of Seven (now known as the Indigenous Group of Seven) in Winnipeg in the 1970s.

“I know that for many years, public collections have been looking very carefully at their holdings of Norval’s work to make sure they’re right, and some [fraudulent] works have been sussed out that way,” Sen. Bovey said.

But, she added, “I think many people were duped.”

‘Everything I produce has a meaning’

Richard Hunt is a Kwagiulth carver who has been vocal about the problem of fake Indigenous art for as long as he’s been making it.

Hunt, whose work has been replicated many times, recalls seeing an image on Facebook of one of his sun masks.

“I was going, ‘Wow, is that ever a nice picture of my work,'” he said. “But then I realized that it was a vinyl cut-out.”

Hunt said there was nothing he could do. He didn’t know who had made the replicated mask or where they lived.

“Everything I produce has a meaning,” he said. “I don’t make a mask just to make a mask. I mean, you could wear it in a ceremony. And all these other people are just in it for the money.”

Hunt wants the federal government to put costly duties on items with Indigenous designs coming into the country. He hopes this would force sellers to increase prices and, ultimately, curtail sales of these inauthentic items.

Bovey believes border checks for art in Indigenous styles could also be a positive step.

“The Copyright Act gives artists the rights of their work, but you have to go after the rights of your work,” she said. That requires hiring a lawyer and most artists can’t afford that expense, she added.

It’s really important that we try to keep our culture. It’s one of the last things we have left.– Richard Hunt

Bovey noted that the American Indian Arts and Crafts Act, which came into effect in the United States in the 1990s, created a fund to assist tribes and individuals with legal fees related to court proceedings. She said a similar fund would be very helpful to Indigenous artists here in Canada.

In September 2022, Bovey asked Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller how the government is addressing the issue of reproduced Indigenous art during the Senate’s question period.

“It’s immensely frustrating to see these original pieces of art being reproduced, and correspondingly undervalued. Currently, there is not a ton of initiatives that are being undertaken to address this,” Miller said.

“I appreciate you highlighting that, and it’s something that, perhaps, can be tackled in the coming years with proper community consultation.”

Makes market more difficult for young artists

Erin Brillon says the internet has made it easy to duplicate Indigenous art.

Brillon, a Haida and Cree artist and business owner, has seen the harm that the industry of copied art has caused her husband, Everson, and other Indigenous artists.

These companies often get shut down, but like a game of “whack-a-mole,” they’ll pop back up a week later after changing their name and web address slightly, Brillon said.

The flood of items at cheap prices certainly makes it harder for young or new artists to get into the market, she said. But the industry of fake Indigenous art affects more than artists’ pocketbooks.

“Our art has been commodified, and the people who profit the most from our artworks are not the Indigenous artist that it comes from,” Brillon continued.

“That’s been happening since the beginning of colonization, since the time that our totem poles have been stripped out of our villages and all of our ceremonial objects have been taken from us.”

Hunt is hopeful that Bovey’s passion for the cause will make a difference. For him, it’s “now or never” to create laws that will protect Indigenous art.

“I hope that we get the government’s ear … [and] get some response from the government in a time of reconciliation,” he said.

“It’s really important that we try to keep our culture. It’s one of the last things we have left.”