What Is New York Fashion Week Without Its Billion-Dollar Brands? | BoF Professional, News & Analysis

This season, New York’s largest labels went rogue. Ralph Lauren, Tory Burch, Michael Kors, Carolina Herrera and Coach are all showing off-calendar. Even Tom Ford, the chairman of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), pushed back the date of his digital show due to “unforeseen circumstances” related to the pandemic.

Several skipped last season, too. But even before the coronavirus made it next-to-impossible to stage a live fashion show in the US, major labels and up-and-comers alike were leaving New York for Europe (Telfar, Altuzarra), or forgoing fashion week altogether (Pyer Moss, Calvin Klein).

A return to “normalcy,” whatever that means, is unlikely to reverse the fragmentation of New York Fashion Week. The CFDA has responded by widening its scope, creating what it has called the “American Collections Calendar,” a sort of catch-all schedule for any American-born (or bred?) designer showing at any point, anywhere in the world.

Ella Emhoff wearing Proenza Schouler Autumn/Winter 2021. Daniel Shea.

“Fashion Week is going to be a looser and looser concept as the world evolves,” Proenza Schouler’s Lazaro Hernandez told BoF during a Autumn/Winter 2021 collection preview. And yet, he and co-designer Jack McCollough chose to show a video within the confines of the schedule, in part because it meant they would be the first to work with Ella Emhoff, the stepdaughter of Vice President Kamala Harris, but also because, as one of the few well-known brands showing, they wanted to support New York Fashion Week as an institution. “We felt protective of it,” Hernandez added.

Gabriela Hearst, whose first collection as creative director of Chloé will debut during Paris Fashion Week, shared a similar sentiment about her choice to show her namesake line via video as part of New York Fashion Week.

“It’s my city,” she said. “I’m showing my solidarity.”

In some ways, despite the growing list of absentees, the schedule feels more crowded than ever. For years, the CFDA was criticised for its overweight calendar, which often featured over 200 shows. Then, it tightened things up to little avail. Now, it’s overspilling again, with more than 90 names on the CFDA’s official list, plus those making their debuts off-schedule. But this time, the packed days are in the spirit of inclusion — and an attempt, it seems, to remind the industry that some of the most successful designers in the world have roots in the US even if they don’t show here.

But for the most part, New York Fashion Week’s organisers — who lean on its media impact to prop up Brand Fashion, just as Hollywood relies on the Oscars to inspire people to watch movies — have been left to focus more than ever on selling the city as the place for smaller, independent brands.

Maisie Wilen Autumn/Winter 2021. Zev Schmidtz.

Collectively, the designers who did make the choice to present this season did not seem as paralysed by fear of the unknown as they had in the autumn, when they were simply churning out products they hoped were sellable instead of honing their brand stories. This season, they appeared to regain some confidence, making things that were not only commercially viable — a requisite for brands that actually depend on their ready-to wear to generate a significant proportion of sales — but felt true to their identities.

In particular, there was a renewed sense of possibility among emerging talents. Kanye West-protégé Maisie Wilen said she hoped “non-fiction” prints — florals overlaid with QR codes that direct the viewer to a product page — would snap the onlooker “back to reality.”

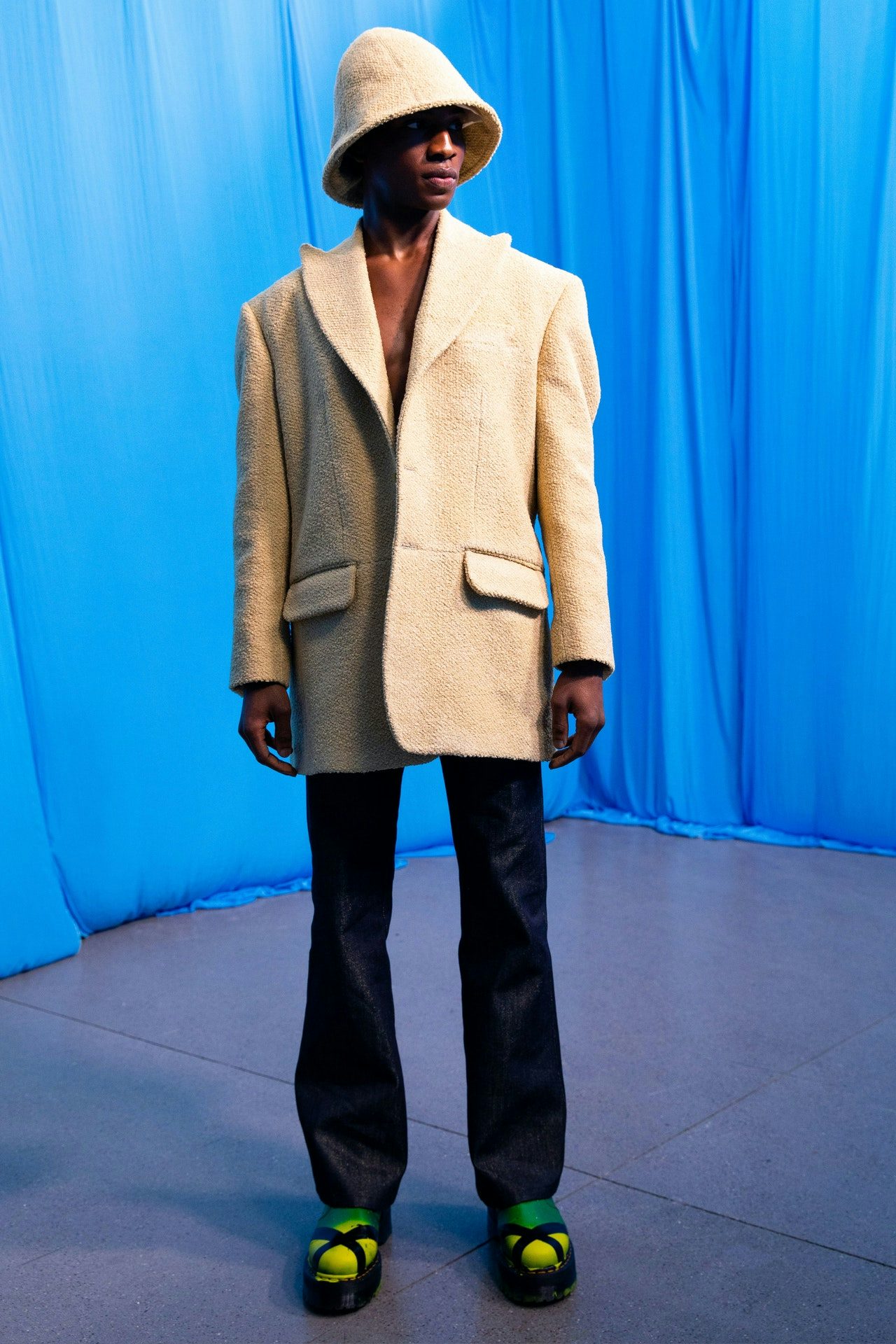

Theophilio Autumn/Winter 2021.

Edvin Thompson, the Jamaican-born designer behind the nascent label Theophilio, increasingly known for its thoughtful interpretations of island style, debuted his first handbag, a shapely hobo he’s calling the “banana boat,” inspired by the pocketbooks carried by his mother. Thompson remains primarily self-funded, but was hopeful that initiatives like the Black in Fashion Council and IMG’s showroom for emerging Black talent, in which he participated, would lead to opportunities. (This year’s plans include the launch of a swimwear line.)

“All of us are asking not just to be in these spaces, but for these institutions to nurture us,” he said. “Funding is a major part.”

House of Aama presented their collection at the Black in Fashion Council and IMG’s NYFW showroom.

Like Thompson, the mother-daughter design team behind House of Aama is telling the story of their heritage. Rebecca Henry and Akua Shabaka’s collections examine and dissect Black southern identity and aesthetics, something white designers have mined for decades. In the past year, as consumers rushed to support Black-owned businesses, spurred by the Black Lives Matter protests, the duo said sales of their delicate blouses and daytime-appropriate lingerie quadruped.

Knitwear designer Victor Glemaud, who has been mentoring Black creatives through his own initiative, In the Blk, echoed the sentiments of several industry veterans. “This season wasn’t about just throwing things at the wall,” he said. “I have always had this outlier business and brand that is category-specific, and as everyone is trying to add this category into their brand matrix, I pushed myself creatively.”

Proenza Schouler also pushed themselves to better balance their own whimsies with customer demand. This season’s shapes were pronounced, but not overly so, accented with easy-to-recognise signatures like slashed knits and contrasting buttons. There was a sense of efficiency, from the cut of the clothes to the size of the collection, but it felt empowering rather than empty, especially given their video’s backdrop: the Herzog & de Meuron-designed Parrish Museum on Long Island, whose heavy cement walls and endless skylights were the perfect catwalk, virtual or not.

Looks from Prabal Gurung’s Autumn/Winter 2021. Leeor Wild.

Prabal Gurung pulled back, too. As a result of the crisis, he had to reduce his staff significantly and designed this collection solo, sketching up 500 illustrations before settling on a concise lineup of flouncy garments he said were a love letter to New York, rendered in red, pink and polka dots. (He was inspired, in particular, by the communities he protested with this summer.) His business manoeuvre was not to suddenly stop making dress-up clothes, but to instead work to reduce his prices by 20 to 30 percent by using lighter, easier fabrics that reflected what his customer, especially what his crucial-to-survival private clients, were after.

A detail from Gabriela Hearst’s Autumn/Winter 2021 collection. Rob Kassabian.

With strong financial backing, Hearst remained steadfast, from aesthetic vision to business vision. Like always, she drew inspiration from a strong woman — this time, the Benedictine polymath Hildegard von Bingen — to develop precisely, yet robustly, across numerous categories. (Her epic trenchcoat programme alone could have been one collection.) Over the past year, she has been as meticulous with her business plan as she is with her garment construction, keeping wholesale accounts to under 80.

Jason Wu was the only well-known designer to stage an in-person show in New York this season. Wu, like many of his contemporaries, came up during a time when building a certain kind of brand, one that could be compared to — and compete with — the storied European fashion houses was the ultimate goal. But after Chinese private equity fund Green Harbor bought a majority stake in his parent company in 2019, he seemed to let go of those old-fashioned ambitions.

This past year, Wu launched four projects, including a collaboration with delivery service 1-800 Flowers, as well as a beauty line, which debuted at Target in January. This season, he invited 20 guests to view his contemporary collection in a “general store,” with custom-made everything from signs to Coca-Cola bottles, reflecting his longtime passion for food and cooking. These aren’t the types of moves you’d expect from a designer of upscale clothing, but they are entirely right for him.

“When you first start out in the industry, it’s like going to a new school. You want to fit in right away,” he said this week. “I would always think about what other people would think … I’ve been freed from the shackles that I’ve actually placed on myself.”

Billion-dollar brands or not, nebulous parameters or not, New York Fashion Week doesn’t seem to be going anywhere anytime soon. (People crave structure and organisation.) The hope, however, is that instead of going back to the way things were, designers will continue to prioritise their own way of doing things.

Related Articles:

The Unbundling of New York Fashion Week

Will New York Fashion Week Survive the Pandemic?

The Other Fashion Month