Vivienne Westwood, Priestess of Punk, Has Died

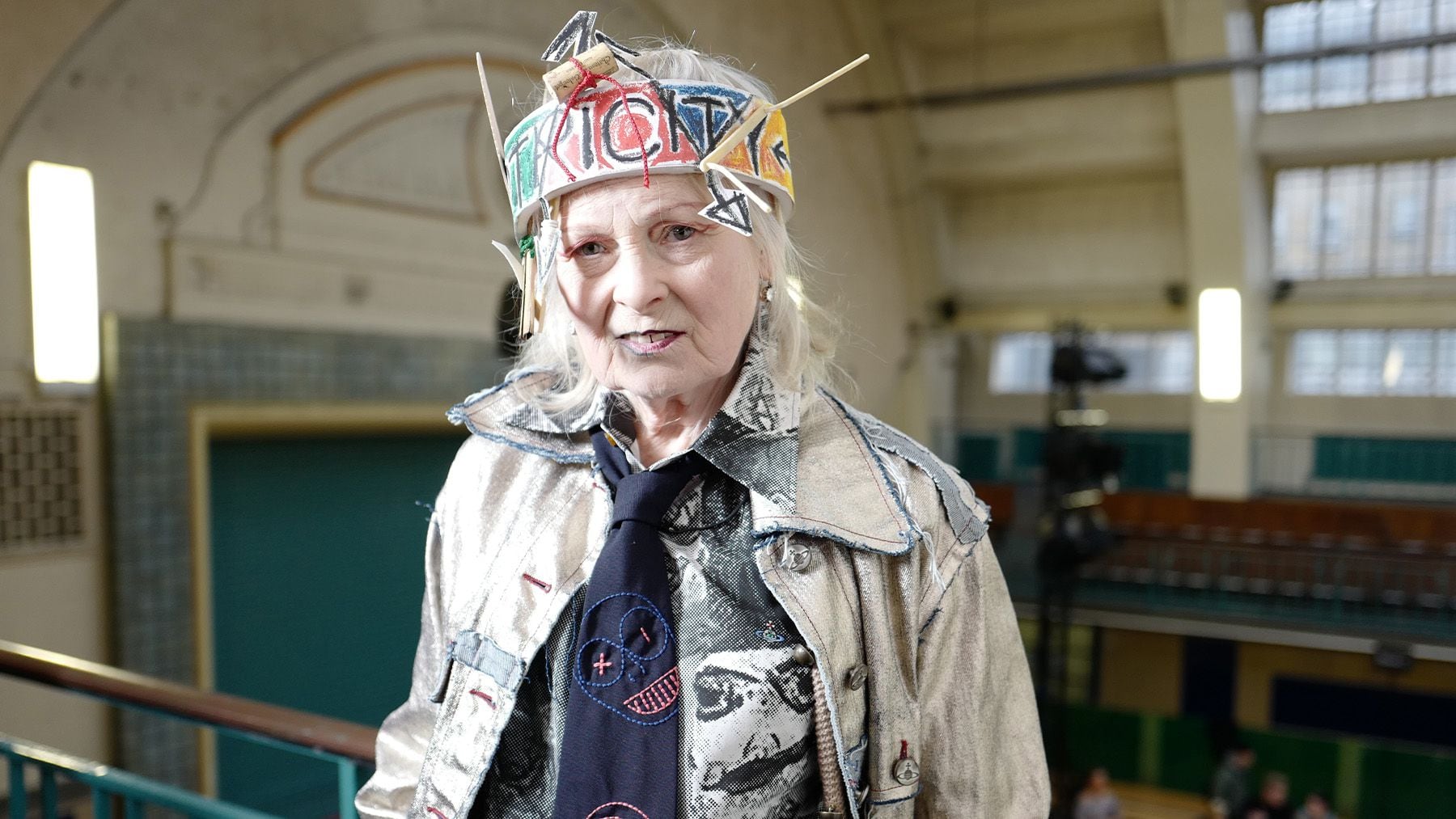

Vivienne Westwood, the maverick UK fashion designer whose five-decade career originated in the mid-1970s punk movement in London and who remained devoted to its ethos of anti-establishment agitation throughout her life, has died at the age of 81. Her brand announced the news of her death.

At the dawn of the punk era, Westwood, with her then partner Malcolm McLaren, helped to invent its “look” with designs that ranged from shredded T-shirts to bondage suits, emblazoned with anarchist symbols, Nazi swastikas, inverted crucifixes and words like “DESTROY.” Dressing the Sex Pistols, who McLaren managed and promoted, she created a vocabulary of provocation that would not only shake up British fashion of the times, but also go on to define her own runway collections and influence the work of generations of designers to come.

A working-class girl from Derbyshire, who was largely untrained in fashion, Westwood was a primary school art teacher when she met McLaren in 1965 at the age of 24, already a young mother and separated from her first husband. Within a few years, she became the spikey-haired high priestess of punk who commanded London’s burgeoning counter-cultural movement while selling Teddy Boy clothes and bondage jeans from a cult retailer on the King’s Road. That she would ultimately be perceived as one of the most influential British designers of the 20th century, and alternatively as a batty eccentric for her political fulminations against consumerism and capitalism, underscored Westwood’s position as a fiercely independent creator who would help shape but never quite fit into the mainstream.

“We wanted to undermine the establishment,” Westwood once said. “We hate it. We want to destroy it. We don’t want it. We were youth against age, that’s what it was.” For the usage of symbols such as the swastika and Third Reich eagles, she would never apologise, citing her idol Bertrand Russell’s mantra that “orthodoxy is the graveyard of intelligence.”

“The way I rationalise it is that we have every right to do it, because what we are saying to the older generation is: ‘You’ve mismanaged this world, and we don’t accept any of your advice, and what’s more, we don’t accept any of your taboos, and, you know, we are just going to confront you with all this.’”

Her appearance, too, was calculated: The alabaster skin of a classic English rose, her hair worn in tightly rolled blonde curls or dyed an electric shade of orange, makeup applied with a child’s hand and a pop artist’s palette, looking both slightly disheveled and slightly regal as she bicycled through the streets of London and then tore through the racks of her Battersea studio, which she ruled with the prickly displeasure of a mad headmistress. In interviews, she could be both disarmingly frank and maddeningly demanding, speaking at length about the perils of climate change when asked about hemlines and veering into non sequiturs about fracking or fashion magazines while throwing verbal darts at McLaren, Margaret Thatcher or Catherine, Princess of Wales.

As much as she delighted in shocking people, she often did so guilelessly, as in 1992 when she arrived at Buckingham Palace to receive an Order of the British Empire (OBE) from the Queen, did a little twirl in front of the photographers causing her skirt to flare up, and revealed to the world without the slightest hint of embarrassment that she was not, in fact, wearing any underwear. Or as she did in 1989, when Westwood appeared on the cover of Tatler uncannily impersonating Thatcher, dressed in a suit that the then prime minister had ordered but not yet collected. The headline: “This woman was once a punk.”

To some degree, Westwood’s antics overshadowed her work as a designer and certainly cost her the business opportunities that might have made her company a bigger financial success. “Though Vivienne has consistently been the first to introduce new looks, she has consistently failed to capitalise on her fashion lead,” wrote Jane Mulvagh in her biography, “Vivienne Westwood: An Unfashionable Life,” originally published in 1998. “She has absolutely no business acumen.” Sales of the brand, which has been under the creative helm of Westwood’s second husband, Andreas Kronthaler, since at least the last decade, reached about $40 million in 2015. But despite her lack of commercial success, her ready-to-wear collections, which she began creating in the 1980s around the time of her separation from McLaren, have had a lasting impact on fashion and the broader culture.

Her first catwalk collection, “Pirates,” in 1981, was significant for adapting lines from historical dress directly to the modern moment, rendering flouncy skirts, tiered blouses and low-slung trousers — their patterns made after the originals in the National Art Library of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum — in bright overdyed sunset colours and serpentine prints that presaged a decade of designers shamelessly appropriating period and ethnic costumes. Some of her most famous styles included the “Mini Crini,” a starkly shortened version of the 19th-century hoop skirt bedazzled with Minnie Mouse spots and colours; corsetry-detailed bra tops and bustiers worn on top of the clothing, preceding Jean Paul Gaultier’s conical bras by several years; and parodic twists on various staples of English upper-class dress, from tweed schoolgirl coats to twinsets and pearls. Her Harris Tweed collection from 1987 revived fashion’s interest in traditional English fabrics that had long been out of style, much as Westwood’s patronage did for the fine knitwear manufacturer John Smedley, which produced her cropped cardigans.

“Vivienne’s effect on other designers has been rather like a laxative,” English designer Jasper Conran once said. “Vivienne does, and others follow.”

Vivienne Isabel Swire was born April 8, 1941, in Glossop, Derbyshire, the first of three children of Gordon and Dora Swire. Her father came from a line of cobblers and worked as a storekeeper in an aircraft factory during the Second World War. Her mother was a weaver at a local cotton mill. Later, they ran a grocery store and a post office, maintaining a thrifty, working-class lifestyle at their small home near Tintwistle. As a sexually confident teenager in post-war England, though, Vivienne began to chafe at convention, dressing in tight pencil skirts that she customised from her school uniforms and dying her hair different colours from one week to the next. When the family moved to Harrow, in northwest London, in 1957, she enrolled in a grammar school and studied jewellery-making at Harrow Art School but left after only one term and took a series of odd jobs, first as a typist and then a primary school teacher.

In 1961, she met Derek Westwood, a charming, one-time tool shop apprentice who later managed a club, at a local dance and married him the next year. Their son, Ben Westwood, was born in 1963. Though her youth had been a happy time, Westwood also complained of feeling stifled by a life with little creativity or culture. “I didn’t know how a working-class girl like me could possibly make a living in the art world,” she said. “Living the American Dream is what that is, and I realised, no, what a load of bollocks that is.” The marriage ended in divorce in 1966.

Through her brother Gordon, Vivienne was introduced to McLaren, a fellow art student at Harrow who shared her distrust of authority and in whom she saw an opportunity to shake off the effects of her provincialism. “I knew I was stupid, and I had to discover what was going on in the world,” Westwood said. Soon, they were living together in a rundown house with a group of film school students, along with Westwood’s son. Westwood went back to teacher training college while she and McLaren, awkward and domineering, and already obsessed with aesthetics, made costume-jewellery crosses to sell at the Portobello weekend market in Notting Hill. And though Westwood would say she was never in love with McLaren, a complicated figure who rejected marital conventions and was prone to violent outbursts, they had a son, Joseph Corré (after McLaren’s wealthy grandmother’s maiden name), in 1967 and their relationship lasted for 15 years. McLaren had been attracted to various radical movements and saw Westwood as something of a muse, someone whose politics he could shape. He had a sense that with her natural talents, fashion could become the tool they used to attack the system.

McLaren and Westwood became fixtures of the burgeoning “retro-chic” scene on the World’s End section of the King’s Road, where they shopped for brothel-creeper shoes and glam neon or animal print velvet trousers at stores like Mr Freedom. In 1971, McLaren, who graduated from film school that year at the age of 25 and needed income, decided to sell a collection of old rock-and-roll records and found a shopkeeper willing to give him a space at Paradise Garage at 430 King’s Road. “Between us and my girlfriend Vivienne Westwood we set out to make an environment where we could truthfully run wild,” McLaren wrote in an essay that appeared in The New Yorker in 1997. “The shop rarely opened until eight in the evening, and for no more than two hours a day. More important, we tried to sell nothing at all. Finally, we agreed that it was our intention to fail in business and to fail as flamboyantly as possible, and only if we failed in a truly fabulous fashion would we ever have a chance of succeeding.”

They did both, several times. The store’s first name, In the Back of the Paradise Garage, was quickly replaced by Let It Rock, which better suited the free-spirited environment that attracted artists and musicians, where 1950s rock memorabilia and vintage Teddy Boy clothes were assembled in what McLaren described as a sort of anti-hippie protest. “Teddy Boys are forever, Rock is our business,” said a sign on the wall. Ringo Starr and David Essex outfitted their characters for the rock film “That’ll Be the Day” there. When the vintage designs sold out, Westwood began making copies in immaculate detail, in effect learning the mechanics of tailoring as she unstitched the originals and created replicas with the same authentic fabrics and buttons.

In 1973, the store became Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die, selling motorcycle styles inspired by James Dean and Marlon Brando, and, significantly, their first rock slogan T-shirts, tarted up with zippers at the nipples or clear plastic pockets. McLaren’s obsession with 1950s pinups of women who appeared to have just been washed ashore in torn clothing, which decorated the store, was directly linked to the torn and destroyed clothing Westwood designed. In one example most coveted by collectors, as only about a dozen were ever made, Westwood embellished T-shirts with the words Rock or Perv, stitching the letters in chicken bones sourced from the Italian restaurant across the street.

In 1974, they changed the concept, once again, to SEX, a lurid idea that McLaren believed would seduce (or antagonise) customers into revolt, with sadomasochistic and fetish gear like bondage pants with a zipper that extended from the front fly all the way up the back. The store windows were filled with naked, headless mannequins posed as if engaged in an orgy. This period produced infamous T-shirt designs including one celebrating the Cambridge Rapist, others depicting fornicating Disney characters, one printed with a pair of naked female breasts on the chest, and the notorious Two Naked Cowboys shirt that led to McLaren and Westwood being arrested in 1975 on indecency charges.

“Every time we changed the name of the shop, we changed the clothes,” Westwood said in the 2018 documentary “Westwood: Punk, Icon, Activist.” “Malcolm had the idea we were going to confront the establishment through SEX because, he said, England is the home of the flasher. His slogan was Rubber Wear for the Office. He was very clever, Malcolm, literarily and everything, except he never read anything.”

It was here that the defining elements of punk took their clearest shape, even though historians will debate whether the movement originated in London or New York. After members of the New York Dolls visited the store, McLaren followed them to the United States to work as their manager for a brief period before establishing the Sex Pistols in London in 1975. Through the Sex Pistols, whose songs “Anarchy in the UK” and “God Save the Queen” captured the nihilistic rage of a nation in decline, McLaren created a vehicle to express his anti-establishment ideas through music, fashion and messaging. Westwood designed their scandalous clothes under the label “Seditionaries,” as the store was renamed in 1976. It featured an interior inspired by the bombing of Dresden in the Second World War and a shelving display that housed a caged live rat.

Clothes were a vital part of the Sex Pistols’ image — with their lyrics printed across their chests on T-shirts that were simultaneously sold in the store, one of the first and most potent marketing partnerships between music and fashion, albeit one that was as short lived. The Sex Pistols disbanded in 1979 after Sid Vicious died of a drug overdose, and the store became World’s End in 1980, selling rock fashions related to McLaren’s next acts, Adam and the Ants and Bow Wow Wow. These included pirate costumes as a coy reference to McLaren’s advocacy of listeners taping songs directly from the radio, rather than paying for them.

But Westwood became disenchanted with punk and had the confidence to envision herself as a serious designer, turning her eye from the ugly to the beautiful. Her interest in historical research led her to the defiant dress of post-revolutionary French republicans that inspired her first designs and became the foundation of her first runway show in 1981, known as the Pirates collection. Staged at the Pillar Hall in Olympia before an audience that included Boy George, Adam Ant and Mick Jagger, with models choosing their own clothes and mismatched hairstyles and shoes, the show marked a turning point that legitimised Westwood among the fashion press and resulted in orders from retailers like Bloomingdale’s, Henri Bendel and Joseph.

With her success, she threw herself into research, sampling ethnicities and eras from Napoleonic to Native American in collections called Savage and Buffalo that were overwhelming in their DIY collaging and haphazard layering of shapes. The styles were oversized and often falling off the body. Westwood’s seemingly instinctive approach to fashion was in fact well devised and attributed with starting any number of trends that followed, such as innerwear-as-outerwear, asymmetric cuts and deconstruction. Soon she was invited to show her collections in Paris, where her 1983 Witches collection featured prints by Keith Haring, and active sportwear and sweatsuit pieces that were championed by Madonna, resulting in lucrative commercial orders, but also financial turmoil when Westwood and McLaren’s personal relationship further devolved into acrimony and the couple finally split.

Westwood was left with enormous debts and had to file for personal bankruptcy in the UK. She fled to Milan, where she took up with Carlo D’Amario, an Italian commodities trader who introduced her to Elio Fiorucci, who hired Westwood for freelance design. Two years later, she reached an agreement with Giorgio Armani to produce her collections, but following the death of his partner, Sergio Galeotti, in 1985, Armani cancelled the deal and Westwood returned to London with just her finished samples from the Mini Crini collection. Back at 430 Kings Road, Westwood, with a loan from her mother and the help of her sons (Ben Westwood became a fetish photographer and Joe Corré a co-founder of Agent Provocateur), she sold the samples in the dark, since the electricity had been shut off.

Still, Westwood proved remarkably resilient. Encouraged by the London designer Jeff Banks, she bounced back with her Harris Tweed collection, which seemed to hit just the right note in parodying British dress. D’Amario co-signed a bank loan that enabled her to carry on, and he served as manager of her Italian operation before eventually becoming her business partner.

This coincided with Westwood’s desire to move away from street fashion and to be accepted by the London elite, who had largely shunned her for her association with the underground. It had bothered Westwood that other designers were profiting from her ideas, and that her validation had come from retailers and editors outside the UK. This changed in 1989, when Women’s Wear Daily editor John Fairchild, in his book “Chic Savages,” wrote that all fashion hangs on the golden thread of six designers: Saint Laurent, Armani, Ungaro, Lagerfeld, Lacroix and, to the astonishment of many, Westwood. After being overlooked for years, she won Designer of the Year at the British Fashion Awards in 1990 and 1991.

While the 1990s brought Westwood global acclaim, and lucrative licenses for hosiery, bridal wear and sub-brands that focused on denim and mainstream designs, her affinity for chaos did not wane, and her label’s annual turnover hovered around just £600,000. “I am always known as the Queen of Punk. I feel that of all the designers in the world I am the only person left who someone could make millions and billions from,” she said. And yet on more than one occasion she was passed over by investors and for lead design roles at houses like Dior.

Westwood had by then taken up with Kronthaler, an Austrian art student 25 years her junior who she had met while serving as a visiting professor of fashion at the Vienna Academy of Applied Arts. And while his presence and sudden authority in the studio raised eyebrows and caused much backbiting, Kronthaler also brought order to the label’s production, encouraged Westwood to court the supermodels who would further her brand exposure, and became Westwood’s sparring partner, fuelling her creativity. They married in 1992, and Kronthaler took over creative direction of the label. Their partnership also enabled Westwood to reconsider her purpose, and she turned her attention from the establishment to “the concept of civilisation itself,” as she said upon receiving her OBE that year. (She advanced to Dame Commander of the OBE in 2006.)

Meanwhile, she had created such a rich archive of work — historical garb, old masters, English tailoring, voluptuous figures and exaggerated proportions (such as the 10-inch platform shoes that famously felled Naomi Campbell in 1993) — that her lower-cost, higher-volume Red Label and Anglomania collections were finally able to bring her some degree of financial comfort, generating more than $20 million in annual sales. D’Amario, working with Staff International in Italy, was producing 40,000 garments per season by 1998. In 2004, her achievements were celebrated with a critically acclaimed retrospective at the Victoria and Albert Museum — surprisingly she said then that she didn’t want to be associated with punk.

“At the time I felt very rebellious,” she told The New York Times at the retrospective opening, “but I now realise there’s no point in it. The urban guerrilla was essentially what we were after, but I don’t believe there is a crusade to be waged by wearing clothes. You just become the token rebel who persuades everyone they are living in a free society. Society tolerates its rebels because it absorbs them into its consumer society. You become part of the marketing. Everything comes with a label.”

Even while Westwood remained active in fashion, she used her fame in her senior years to promote her political passions, sometimes to the detriment of her reputation. She became a spokeswoman for Climate Revolution and travelled with Greenpeace to the Arctic to inspire young people to engage with the environment and often peppered her shows with political messages. In 2015, she drove a tank to then British prime minister David Cameron’s Oxfordshire home to protest fracking. In 2020, she dressed in a yellow suit and was suspended in a cage — symbolising a canary in a coal mine — to draw attention to the plight of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, whom she had also celebrated in her collections since 2012. While her messages could be convoluted, her goal, she said, was pure: to fight injustice.

“When I was little, I saw a picture of the crucifixion and it really did change my life,” she said in the 2018 documentary. “I thought to myself, my parents have been deceiving me — they told me all about the Baby Jesus, but they never told me what happened to him. And I thought I just can’t trust the people in this world. I’ve got to find out for myself. I did feel I had to be like a knight to stop people doing terrible things to each other. And I think that that’s had something to do with my fashion as well. It’s always got to be that. You know you’ve got to cut a figure and be prepared for action and engagement with things.”