Tim Blanks’ Top Fashion Shows of All-Time: Alexander McQueen Spring/Summer 1998 | Fashion Show Review, Tim’s Take, Tim Blanks’ Top Fashion Shows of All-Time

It was a dark and stormy late September night inside the derelict Gatliff Road bus depot deep down in London’s Victoria. Thunder rattled, lightning flashed, the dank stench of decades of exhaust fumes assaulted the olfactories. Alexander McQueen’s 10th show was three-quarters of the way through, when everything suddenly stopped. The models had been walking on huge Perspex tanks filled with water, lit from below so they glowed. But now there were no more models, no more music, no more light, and the tanks were slowly filling with a black contagion, their glow steadily dimmed by ominous clouds of ink. Then, miracle of miracles, a golden rain began to fall. The first ticktock notes of Ann Peebles’ “I Can’t Stand the Rain” accompanied the return of McQueen’s models, walking through the darkness and the downpour, makeup streaming, clothes clinging.

The way this moment lives in memory, it might possibly be the most dramatic I’ve experienced in 35 years of show-going. I choked, just like the dowagers I’d seen at the couture. Even the backstory didn’t diminish my emotional engagement. American Express had decided to sponsor a London designer, and settled on McQueen as the first recipient of their largesse. They were also launching their Gold card in the UK. So, McQueen titled his 10th show “Golden Shower” to celebrate his sponsor. Amex blanched. “Untitled” was McQueen’s deliberately unimaginative compromise, even if the invitation was piss-yellow in a sly nod to his original idea. And he managed to hold fast to his climactic golden shower. Truly a one-time-only in the history of fashion spectacle, though this particular season — Spring/Summer 1998 — in London could claim an equally startling finale in Hussein Chalayan’s six chador-clad women, the first dressed top to toe, then ever-shortening until the last had only her head covered. She was otherwise naked. The designer claimed it was his comment on his own Muslim culture’s oppression of women.

If Chalayan’s was quite a bit starker as a closing gambit, McQueen’s had an element of risk that was equally fundamental to his show’s impact. Set designer Simon Costin had no idea if the ink would suffuse the tanks in time, or even at all. It was a typically audacious gamble. A year later, McQueen would set Shalom Harlow spinning under the invasive ministrations of spray-painting robots, another stunning special effect that could not be dress-rehearsed. But the drive to defy limitations and to twist the elements to his own devices were among McQueen’s signatures from the very beginning. Here, the element was clearly water. A season later, it was fire, with Erin O’Connor twisting inside a circle of flames as his very own Joan of Arc. There was a fury in him that would never settle for no.

But that furious drive meant that McQueen was often an extremely difficult designer, especially in these earlier presentations where his reach and his grasp weren’t totally reconciled. It wasn’t obvious in the dark drama of the moment. Only later would the peculiar excess insinuate itself: the 100 looks, the exaggerated proportions, the air of fetishistic transgression, with skirts cut high in the back to bare the bum and fringing that exposed pierced nipples. The way the male models looked in “Untitled” was particularly striking. Hyper-masculine men were sheathed in bustiers, shoe-horned into Cuban-heeled sandals, not feminised exactly but oddly immobilised hommes fatales. Some of them were wearing silver jawbones by Shaun Leane, like eerie prostheses. The notion of damaged masculinity definitely heightened the impact of the warrior women that McQueen always exalted in his collections, rendered a uniform army here by Guido Palau’s asymmetric wigs. They were tailored into power-shouldered ’40s-styled suits, intarsia-ed, with pencil skirts falling to just below the knee. There was confrontation in perforated leather matched to sheer, flesh-toned tops. The first section of the show closed with a model tightly encased in Leane’s silver ribcage, which turned into a skeletal tail in back, like one of H.R. Giger’s alien designs. For both men and women, the abiding sensation was discomfort.

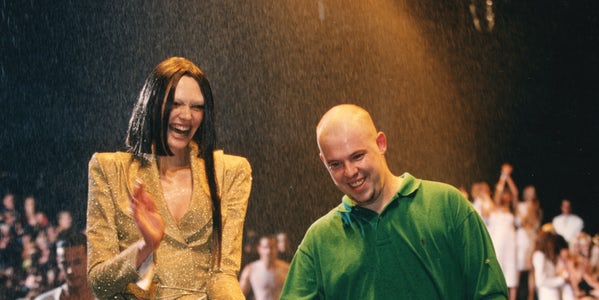

Then came the golden rain, and a whole other collection, almost serene by comparison. All the looks were white, there was a sense of sensuous drape rather than razor-sharp cut, of ethereal spirit rather than the carnal flesh of the first passage. The duality was quintessential McQueen. As quintessential as his final bow with the blonde Brazilian Shirley Mallmann, she Amazonian in a pagoda-shouldered pantsuit, he in a supersized polo shirt, looking oh so bashful.

Innocence versus corruption was another of McQueen’s fundamental face-offs. Backstage, I noticed a model I hadn’t seen before. Everyone was ignoring her, so I did the polite thing and struck up a conversation. She, too, was Brazilian, 18 years old, she told me. Her agent hadn’t been able to drum up any work for her in New York, so he’d sent her off to London, where he felt her out-of-sync-ness might spark more interest. McQueen’s was the first show she’d actually walked in. It’s a challenge to pick her out from the crowd in her Guido wig, but someone had the sense to dress her in an anatomical latex breastplate for the final section which made it quite clear that Gisele Bündchen’s innocence wasn’t long for this world.

The images in this review, courtesy of INDIGITAL.tv | FashionAnthology.com, are not the full Alexander McQueen Spring/Summer 1998 collection.

Click here to read Tim Blanks’ series of the Top Fashion Shows of All-Time.