The Last Soviet Generation | History

Every evening, Soviet army vehicles ploughed the white sand beaches at the shoreline of Soviet Lithuania, on the western border of the USSR. Locals knew not to go to the beach at night for leaving footprints on the perfectly raked sand could mean drawing the attention of the Soviet border troops. But when the soldiers left at 6am, the beaches offered the promise of treasure for the children willing to find it.

Those treasures were items lost at sea – ship rope, Coca-Cola cans, and even plastic toys washed ashore from capitalist countries. To Soviet children, collecting these useless but colourful items with their slight smell of “the other” world offered them a glimpse of what lay behind the Iron Curtain.

Sigita Kraniauskiene, a 50-year-old sociologist and senior research fellow at Klaipeda University in Lithuania, recalls collecting such “treasures” during her childhood and wondering how Westerners lived. “I tried to imagine how Swedish people lived on the other side of the Baltic Sea,” she says.

“Nobody expected the Soviet Union to collapse soon. We grew up behind the Iron Curtain, being prepared to become ordinary and submissive Soviet citizens,” she adds.

But it did collapse. Thirty years ago, on December 26, 1991, the Soviet Union, of which Lithuania was a part, was dissolved. Suddenly, a generation that had grown up under communism, found itself entering adulthood in a newly independent, capitalist state.

Sociologists, like Sigita, and historians have not agreed on a title to define this generation born in the late 1960s and 70s but the Last Soviet Generation, the Transitional Generation and the Threshold Generation have all been used.

“Although there is no unified term, researchers choose adjectives that show the dramatic change,” explains Sigita, whose research focuses on this generation that straddled two social and political systems.

Sigita Kraniauskienė plays kanklės, a Lithuanian folk instrument, dressed in Soviet school uniform [Courtesy of Sigita Kraniauskiene]

Sigita Kraniauskienė plays kanklės, a Lithuanian folk instrument, dressed in Soviet school uniform [Courtesy of Sigita Kraniauskiene]Foreign chewing gum

During the 1980s, on May 1, the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius, would be decorated with Soviet flags. Posters of Soviet leaders Vladimir Lenin and Leonid Brezhnev hung from state buildings and local flower shops displayed buckets of red carnations as Communist Party leaders and common citizens gathered to watch the International Workers’ Day parade on Lenino Prospekas (Lenin Avenue).

Dalia Kedaviciene recalls marching in the parade with a Pioneer drum when she was 10 years old. “I felt proud walking at the front of the parade,” the 49-year-old retired crime prevention chief at Lithuania’s Ministry of Interior explains.

“My childhood was a happy one, for I had nothing to compare it to,” she says, speaking via Zoom from her home in Vilnius. “It was an event when my mom brought foreign chewing gum from her work trips.

“We did not have many food choices, and I recall long lines waiting to buy bananas or books,” she adds, looking into the distance as she remembers her childhood.

Dalia’s father was an electrician, and her mother was a high-ranking official at the Ministry of Interior. Although her mother was a member of the Communist Party, she never instilled communist values in her daughter.

“My mother early on became disillusioned with communist ideals. There was a stark difference between the official narrative and the leadership’s actions,” Dalia says, adding: “She taught me human values: honesty, respect, consideration, and love towards other human beings.”

Display of military might was a staple of the October Revolution parade. Pictured here is from the last in Vilnius in 1990 [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]

Display of military might was a staple of the October Revolution parade. Pictured here is from the last in Vilnius in 1990 [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]Mandarins in summer

For those children who were raised to become members of the Communist Party, there were several options. From the age of seven to nine, they could join the Little Octobrists. Members would wear a ruby-coloured star badge with a childhood portrait of Lenin on it. Nine-year-olds could progress onto the Young Pioneer organisation, where they would be given a red neckerchief to wear with their school uniforms. From age 14 to 28, young people could join the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League, commonly known as Komsomol.

Dmitry Denisiuk, a 55-year-old actor with the Russian Drama Theatre of Lithuania, was an enthusiastic Pioneer. He attended parades, marching competitions, and spent time at Pioneer summer camps. “I was proud to be a Pioneer, and I learned from the Soviet children’s literature that a good Pioneer is studious, honest, and respects adults,” he says, switching between Lithuanian and Russian as he speaks over Skype from a dimly lit room in his flat in Vilnius after a week of new season premiere performances.

“I volunteered to clean the school after classes, collected old newspapers for recycling, and helped elderly ladies to cross streets,” he recalls.

Because of Dmitry’s active involvement in the communist youth groups, when he was 15, his school sent him to the Pioneer summer camp in Nordhausen near Erfurt in East Germany.

It was a typical Pioneer summer camp with cabins, an event hall, a canteen, a laundry and a sports field. Although the state built Pioneer camps across the Soviet Union, spending two weeks at an international camp was an honour afforded to only a select group of youngsters.

Dmitry was one of 20 Lithuanian students sent to the Nordhausen camp. There, he met young people from Italy, France, Poland, Bulgaria, Hungry, Greece, and elsewhere. “It was 1982, the year of the 12th Football World Cup, and we organised our own tournament at the camp,” he remembers.

He recalls being baffled at the sight of colourful merchandise in the stores and baked buns in the coffee shops during excursions to Erfurt and Berlin.

“Our retail stores had no smell, and food shops had a different, more earthy smell of potatoes, cabbage, beets, or carrots. It surprised me to see oranges and mandarins at the store during the summer in Germany. We could buy these fruits only in December in Lithuania. I remember enjoying its citrusy aroma mixed with the sweet smell of chewing gum,” Dmitry says.

At the youth camp, pupils from different countries exchanged T-shirts and souvenirs. “We had nothing to offer but our Komsomolsk pins [small metal badges of a red flag with a portrait of Lenin at the centre], pocket calendars, and postcards with images of Vilnius, Moscow, or the Kremlin,” he recalls. “I wondered if we won Second World War, then why do we have so little nice things compared to other communist or Western countries.”

Dmitry says the situation in Lithuania was better than in Ukraine, where his father was from, and Russia, where his mother was from, but that it was not as rich or colourful as life in East Germany. His parents had moved to Lithuania to escape famine and economic hardship after World War II. His mother worked as a nanny, and his father was a soldier in the Soviet army.

“During summer vacations, we visited my grandmother in a village near the Russian town of Pskov. My parents packed packs of sugar, legumes, and glass jars full of butter submerged in saltwater. At the village’s local store, there were only matches, bread, and vodka,” he remembers.

“As a child, you do not think about the quality of your food and clothes: mother gives you porridge, you put on your trousers, and go to kindergarten,” he says.

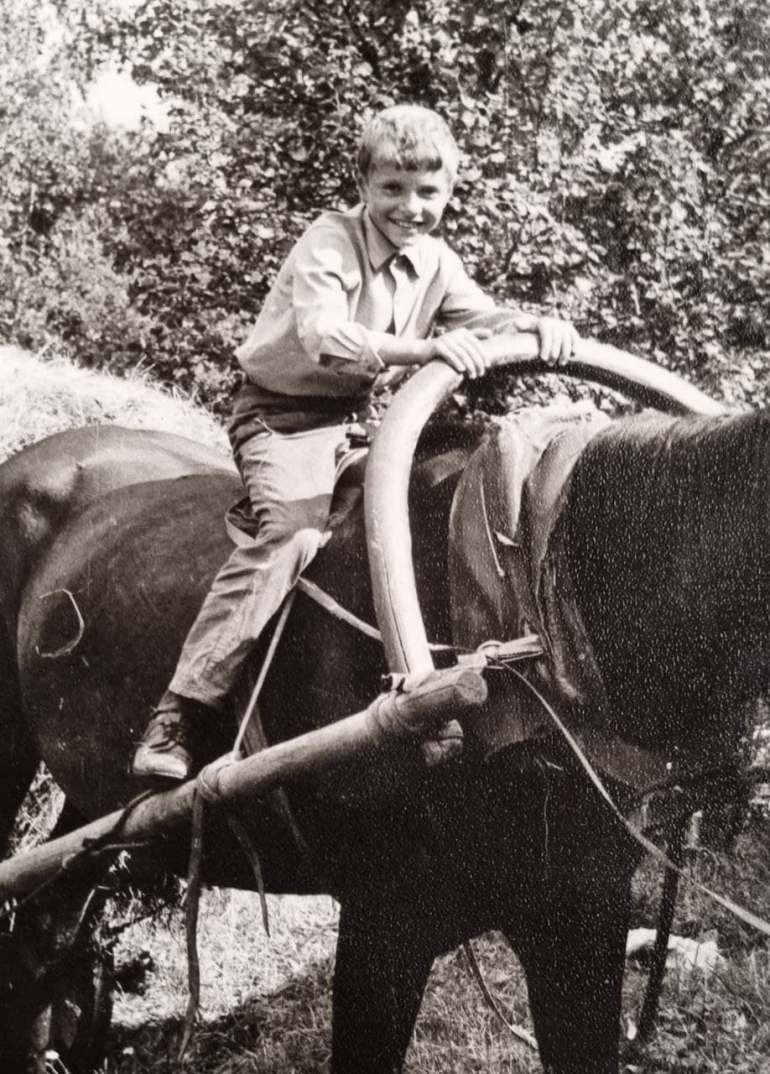

Dmitry Denisiuk was active in communist youth camps as a child and remembers meeting children from non-communist countries at one such camp and being surprised by their non-standardised belongings [Courtesy of Dmitry Denisiuk]

Dmitry Denisiuk was active in communist youth camps as a child and remembers meeting children from non-communist countries at one such camp and being surprised by their non-standardised belongings [Courtesy of Dmitry Denisiuk]A world without colour

“I kept wondering why the Western world is so colourful,” says 48-year-old Audrius Lelkaitis, a freelance journalist who hosts a current affairs radio show called Relaunching Civilisation on National Lithuanian Radio. Once a week, on Saturdays, Audrius asks passersby on the street for their opinion about a current event or a social issue and then invites experts to provide analysis on a matter of concern.

As a teenager, Audrius loved watching pirated Western movies, copied onto VHS tapes. New movies were in high demand and children would pass them around. “It felt like the entire world lived in the Christmas spirit, and we lived in a khaki-coloured barn,” he says.

His father was an engineer and his mother a chemist technician. Both were Catholics who observed religious holidays at home, as attending church was risky. Although they did not support communism, Audrius says they never openly expressed their disagreement with it and led “ordinary, conformist, Soviet citizens’ lives”.

“Hardly anyone treated Soviet pioneer and Komsomol rituals as meaningful. The Last Soviet generation understood the difference between the official domain and private lives. They witnessed their parents’ conformism,” explains Irena Sutiniene, a researcher at the Institute of Sociology at the Lithuanian Social Research Centre.

She says that while their parents were more conservative and preoccupied with providing for their families in a shortage economy, the Last Soviet Generation had more opportunities to travel, had access to a broader spectrum of information and was more liberal.

As a teenager, journalist Audrius Lelkaitis would watch pirated videos from the West and wonder why it was so colourful [Coutesy of Paulius Lileikis]

As a teenager, journalist Audrius Lelkaitis would watch pirated videos from the West and wonder why it was so colourful [Coutesy of Paulius Lileikis]Cartoons, chewing gum, and the death of Brezhnev

Born during an era when standards of living declined as Brezhnev presided over increased spending on defence and aerospace at the expense of industries such as healthcare and agriculture, the Last Soviet Generation experienced shortages of food and household items.

Identical school uniforms, similar clothing, and household items created a limited but familiar world for children in Lithuania and throughout the Soviet Union. Soviet schoolgirls wore brown dresses with white lace collars, and boys dressed in navy blue suits. The school year started on September 1, and all students opened the same textbooks.

Lithuanian children played with toys manufactured by three Soviet Lithuanian toy companies operating under the Neringa conglomerate or brought to Lithuania’s retail stores from other Soviet republics. There were green and yellow plastic trucks, blinking dolls that made a crying sound, or wild animal figurines made of rubber.

“There were not so many toys, and I remember making erasers out of colourful flip-flops found on the shore,” Sigita says.

Imported chewing gum covers were considered a collectable rarity. Some children had notebooks filled with glued wrappers: yellow Juicy Fruits, smiling Donald Duck, or Pink Panther.

Simplistic and identical Soviet residential buildings created featureless living micro-districts such as Pilaite in Vilnius [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]

Simplistic and identical Soviet residential buildings created featureless living micro-districts such as Pilaite in Vilnius [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]While their parents were at work, many children spent their afternoons at playgrounds, surrounded by identical Khrushchyovka houses, the cheap five-storey brick buildings named after the first secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, who aimed to provide families with modern flats in the 1960s. Even the interior of the flats, with their similar lacquered dining room sets and identical household items, felt familiar. “If we meet a person of our generation, we find a common topic quickly. Everything was standardised,” says Sigita.

At the end of each evening from 8.30pm, “throughout the entire country, children would disappear from the playgrounds to watch cartoons”, says Irena.

Lithuanians could watch three channels on their TVs, two of which were broadcast from Moscow in the Russian language.

But on November 10, 1982, there were no cartoons on TV. Instead, the national broadcasters from Moscow and Vilnius disrupted the regular programming following the death of General Secretary Brezhnev, who had been at the helm of the Soviet Union for 18 years. The Last Soviet Generation had grown up looking at his portrait on their classroom walls, listening to his New Year speeches and watching him wave at military parades from the Kremlin balcony on the evening news.

“When my father told me about his death, It shocked me. He was immortal to me,” Audrius recalls.

Dalia, who says she barely paid attention to communist propaganda, was surprised by her reaction. “I do not know why, but I cried when I learned about his death,” she says.

Joseph Stalin’s sculpture, like many other monuments of Soviet leaders, was moved to storage during Lithuania’s independence movement [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]

Joseph Stalin’s sculpture, like many other monuments of Soviet leaders, was moved to storage during Lithuania’s independence movement [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]Relearning history, reinventing traditions, and living with no currency

After 50 years of being one of the 15 constituent republics of the USSR, Lithuania declared independence from the Soviet Union on March 11, 1990.

During the first years of Lithuania’s independence, Soviet institutions were transformed, police replaced the Soviet-style Milicija, and churches that had been used as storage buildings or gyms welcomed back worshippers.

While the re-established Central Bank of Lithuania was getting ready to introduce the national currency, the litas, the Russian rouble was replaced by colourful talonai, printed on poor quality paper with images of Lithuania’s wild animals. People nicknamed talonai “vagnorkes” after the prime minister of Lithuania, Gediminas Vagnorius, who twice led the government during the transition period in the 1990s.

Citizens removed Soviet monuments from the squares and historians started rewriting history books. Before becoming a police officer, Dalia studied history at Vilnius University. While the old textbooks were being removed from the library’s shelves, students were left with none, she recalls. “Our professors were teaching from their notes, and we were making copies,” she says.

Newspapers changed their names. The daily Komjaunimo Tiesa (Kosomolsk’s Verasity) became Lietuvos Rytas (Lithuanian Morning), the education magazine Tarybinis Mokytojas (Soviet teacher) became Tevynes Sviesa (The Light of the Homeland), and the Sirvinta regional paper Lenino Veliava (The Flag of Lenin) became Sirvinta.

Book stores displayed works banned during the Soviet era, including masterpieces such as Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak, The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov, The Gulag Archipelago by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell.

“We felt a little bit lost,” says Sigita. “We were used to someone telling us who is right and who is wrong. Now we had to absorb new information and make choices.”

The Last Soviet Generation had not only to relearn history but also to reinvent traditions. For 70 years, atheists, following the Marxist view “religion is the opium of the people”, waged war on religious practices in the state. Scientific atheism, the official term for the Communist Party’s philosophical worldview, created ceremonies that replaced religious ones. New Year’s Day celebration replaced Christmas. There was Constitution Day on October 7, Revolution Day on November 7, Victory Day on May 9, and International Workers’ Day on May 1.

“I did not know what Christmas or Easter were,” Dalia says. “We celebrated only New Year’s Day and birthdays in our house.”

Bananas and oranges were a rarity during Soviet times in Lithuania. When the country gained its independence, a bigger variety of merchandise arrived at its stores, markets and the stalls such as this in Laisves Aleja in Kaunas town in 1994 [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]

Bananas and oranges were a rarity during Soviet times in Lithuania. When the country gained its independence, a bigger variety of merchandise arrived at its stores, markets and the stalls such as this in Laisves Aleja in Kaunas town in 1994 [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]An introduction to the wild West

“During the Soviet times, life trajectory, official norms, and the structural conditions governing life were very clear. The Last Soviet Generation, with its freedom, had pressure to make the right choice in a changing society,” Irena explains.

While many enjoyed these new freedoms and opportunities, there was also a sense of insecurity. With the collapse of the centralised economy came unknown phenomena such as unemployment and a shortage of essential items. This, combined with the fact that independent Lithuania had to build a new law enforcement system, including police forces, courts and prisons, and to pass new laws to replace old Soviet legislation, created the ideal conditions for crime to flourish.

“The crime situation rapidly deteriorated in Lithuania, and it remained for the next 10 years until our police and legal systems became stronger,” explains Arturas Kedavicius, a retired general manager of the Lithuanian Emergency Response Centre that handles emergency and crisis calls, who also worked as a police officer at the independent Lithuanian police force.

“When the Russian Army was leaving Lithuania, soldiers sold everything: gas, equipment, metal, and guns. During the Soviet times, there was a minimal number of guns among civilians, but once the Soviet Army left the country, you could buy guns in the market,” Arturas adds.

According to the Lithuanian Department of Statistics, the rise in crime started in 1988. The number of reported crimes increased from 21,300 to 31,300 in a single year in Lithuania. In 2000, police registered more than 82,300 crimes in Lithuania. Many criminal groups and individuals started trading metal, gas, and raw materials obtained from state factories, collective farms, or from Communist Party properties that were going through the process of transitioning to private ownership. Some new “businessmen” even removed sewage hole covers from the streets, melted them, and sold them as metal.

The first years of freedom in Lithuania were marked not only with new opportunities but also economic challenges. People shop for Easter at Kalvarijų market in Vilnius in 1994 [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]

The first years of freedom in Lithuania were marked not only with new opportunities but also economic challenges. People shop for Easter at Kalvarijų market in Vilnius in 1994 [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]Expensive cars with tinted windows became a new sight on the country’s roads. Residents started installing double entrance doors, and a chorus of car alarms would often be the soundtrack to a bad night’s sleep.

“During the Soviet times, youth either went to a trade school or continued their studies at a university,” Irena explains. “During the transition period, some started businesses instead of continuing their education.”

But these new businesses often became targets of racketeering by organised crime groups.

Lithuanian Department of Statistics’s records show that intimidation and murder by organised crime groups peaked in 1994 and 1995, with police in the country of approximately three million recording more than 500 murders in each of those years.

Arturas says that most business people were subject to intimidation and violence from organised crime groups. “Business owners who refused to pay fees for ‘protection’ to racketeers would receive a warning: criminal groups would burn, damage, or confiscate their property. If business owners continued to refuse payment, then racketeers would beat them, and their families received threats. The most stubborn businessmen got shot or exploded in their cars.”

With applauds and ovations, citizens removed sculptures of Soviet leaders, symbols of oppression, such as this Lenin statue in Lukiskiu Square in Vilnius on August 23, 1991 [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]

With applauds and ovations, citizens removed sculptures of Soviet leaders, symbols of oppression, such as this Lenin statue in Lukiskiu Square in Vilnius on August 23, 1991 [Courtesy of Paulius Lileikis]‘Having freedom is better’

Irena believes that the Last Soviet Generation was shaped by the economic and political changes they experienced rather than their Soviet-era upbringing.

“Lithuania’s independence movement coincided with our generation’s beginning of independent adult life. We felt we had limitless opportunities and energy to achieve it,” says Dalia. She believes that growing up in the Soviet Union taught her to be collaborative, supportive of others, and have a less individualistic approach to life and relationships.

During the years of transition, Dmitry, who is from a Russian-speaking ethnic minority family, says he did not feel fear but hope and excitement about the opened borders and access to international literature and art.

“[During the Soviet era] the majority believed that if you thought differently than the majority, you were a dissident or a dangerous maverick. It took me a long time to re-evaluate this habit and adapt to new ways of thinking. Sometimes, I think I’ll never get rid of it,” he reflects.

Audrius is grateful for the opportunity to experience life in two different political systems: “We felt economically, but not politically, safe living in the socialist system. Although we waited in lines for basic food or household items, we were not afraid of losing our jobs. Now we have to compete and prove our value.”

Still, he adds, “while no system is perfect, having freedom is better”.