The Future of Asia’s Fashion Weeks | Intelligence, BoF Professional

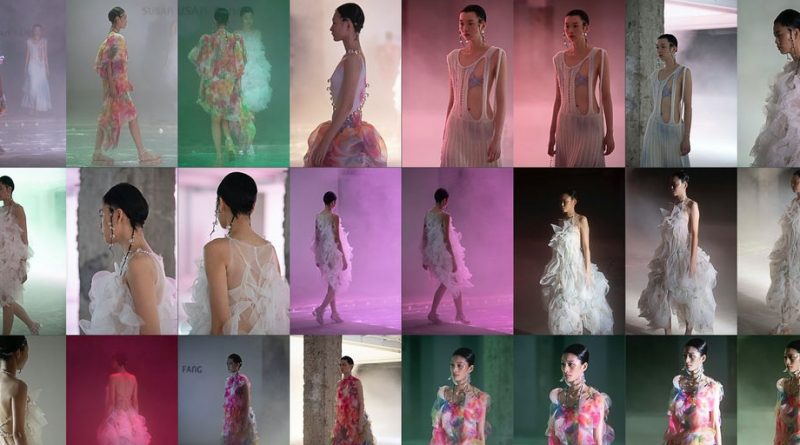

LONDON, United Kingdom — The same day that New York designer Jason Wu staged a socially distanced runway show for a pared-down guest list of 36, Susan Fang unveiled her Spring 2021 collection to almost 400 industry onlookers (many of whom had flown in from cities across China) in Shanghai’s Jing’An district.

On the runway, models were encased by weightless frocks in watercolour hues, an effect created by sandwiching coloured feathers between layers of organza. Save for the fact that all guests and staff voluntarily sported face masks, the show, which took place ahead of Shanghai Fashion Week’s official 10-day schedule ending October 18, was a flashback to simpler times.

Rebirth was the collection’s theme. Apt, considering that over 90 brands held physical shows in Shanghai after last season’s fully virtual showcase, not to mention the speed at which China’s economy is recovering from its Covid-19 outbreak.

However, Asia’s two other industry events aren’t quite back in full swing. Tokyo’s Rakuten Fashion Week (October 12-17) and Seoul Fashion Week (October 25-28) are part and predominantly virtual affairs respectively, with live events executed cautiously and on a smaller scale. With international travel at a dead stop, designers from the three markets are missing out on opportunities to rub shoulders with top global press and buyers when their support is most needed.

As further uncertainty looms, creatives, buyers, editors and executives from Asia’s three fashion capitals reflect on the cultural and technological shifts taking place this season and how they’re evolving with the times.

The Digital Touch

Government restrictions and subsequent re-openings pushed brands and event organisers across the three fashion capitals to experiment with new ways of working. A season later, brands have become more confident in their approaches.

Granted, organisers are still erring on the side of caution. Fang notes that rumours of another wave of infections encouraged attendees and staff in Shanghai to stay diligent. In Tokyo, Japan Fashion Week Organisation (JFWO) Director Kaoru Imajo prepared for both best case (part physical, part digital) and worst case (fully virtual) events until the situation stabilised in August. At venues, PPE and temperature checks were the norm, in addition to CO2 sensors to detect overcapacity.

In Seoul, health restrictions forced the Dongdaemun Design Plaza to shut down for the year. “We had no choice but to go digital,” said Seoul Fashion Week Director Jeon Mi-kyung, who is having to reckon with these challenges as a newcomer (she took over the post from Jung Kuho in October 2019). Without an official event venue, smaller brands have had trouble securing spaces for shows and presentations, pushing designers to think on their feet.

The EENK VR ‘store,’ where customers can navigate their physical store and shop the brand’s Fall collection. | Source: EENK

Last season, Hyemee Lee, the Seoul-based designer behind womenswear label EENK, launched a virtual reality presentation to showcase her Fall 2020 collection. “The response [was] pretty explosive,” she said, noting her site recorded its highest traffic volumes and online sales on the day of the launch. Last season’s success prompted her to show her Spring 2021 collection digitally as well.

On EENK’s website, the VR experience has even been brought to consumers, who can shop the previous season’s offerings by “roaming” their store and hovering over items on the racks. It was a solution devised when physical stores were still inaccessible, but one that Lee plans on using in the long term. Lee will partner with showroom agency Future Society and Dazed Korea for digital activations, while also hosting a physical presentation at multi-brand destination Boon the Shop.

Tokyo-based LVMH Prize winner Masayuki Ino also tapped into VR for his label Doublet’s Halloween-themed show. Attendees put on VR goggles to watch a 10-minute horror movie prior to the show, which featured zombie-like models in the brand’s signature sardonic mish-mash of streetwear with tongue-in-cheek references.

Shanghai got a leg in the door in March with its digital, livestream-centric schedule supported by Alibaba-owned e-commerce giant Tmall, but this season the focus shifted back to physical shows, said Shanghai Fashion Week Vice Secretary General Madame Lu. The organisation’s official account on Xiaohongshu drew three million livestream views for shows by labels like Lily and Zhangshuai in a single day; a livestream hosted by top broadcaster Viya for her brand ITIB hit over 20 million cumulative views and drove transactions amounting to 200 million yuan (almost $30 million) on the label’s Tmall flagship store.

Both Tokyo and Seoul are playing catch-up with efforts to bring shows and collections online. On the B2B side, Imajo tapped virtual showroom Joor to help bridge the gap between global buyers and designers in Tokyo, while the likes of Lee in Seoul opted for Le New Black. Both fashion week organisations are zeroing in on B2C: Japanese brands like Hare and Bodysong can now be found on the event’s pop-up store on title sponsor Rakuten’s e-commerce platform.

Meanwhile, Seoul’s Jeon will work with TV programmes and Korean “super app” Naver to stream shows live. Livestream commerce and “see now, buy now” will also be introduced this season. To target Chinese buyers and shoppers, she will link up with WeChat to livestream shows and launch a sales programme for buyers and consumers, the event’s first collaboration with the Chinese tech giant.

“Last season, the abrupt cancellation of Seoul Fashion Week made it difficult for us to discuss collaborations with other platforms or retailers,” said Jeon. “We prepared for this season with [both offline and digital] options in mind.”

The Missing Link

All three fashion weeks had to make do with local guests this season, but in Shanghai, the absence of global buyers held a different meaning. The event, which in the early days featured international names targeting the mainland market, has pivoted to an almost completely homegrown affair. Brands that, years ago, were lauded by western retailers and publications as a new wave of Chinese design talent are less concerned about being recognised on the global stage than they are with targeting local retailers.

“Shanghai Fashion Week’s primary market is China… the most important attendees were never global press or buyers,” said Liushu Lei, half of the duo behind local label Shushu/Tong. The brand held its runway show, featuring floral, gingham and bejewelled takes on its signature babydoll silhouettes, on October 9, and will be selling to buyers via Tube Showroom, one of the cities’ many showrooms and trade shows operating physically again.

Following on from last season’s fully digital schedule, virtual showrooms like Joor and Le New Black remain the solution for reaching buyers abroad. Local buyers, unable to travel abroad for appointments, are increasingly using their budgets to support local talent.

“The fact that they weren’t able to attend this season is sad, but it’s not a life or death situation for us,” adds Lei. “I think that if the event wants to develop further, it should focus on bringing in Asian brands and buyers rather than looking to the West.”

The Chinese market holds more than enough demand for small brands, thanks to its abundance of multi-brand stores, which in recent years have popped up in cities from Chongqing to Xiamen. Comparatively, “the [China] market is so strong,” said stylist and KOL Leaf Greener, who attended Fang’s show among others in the city. “Even if global buyers don’t come it might affect their global exposure, but it won’t hurt their business.”

When Fang’s global stockists closed stores and put orders on hold earlier this year, it worried her. But by July, a surge in Chinese demand meant all of her local retailers were requesting re-stocks and making additional orders. “This summer was such a great sales [period],” said Fang, assuming that the uptick can be partially attributed to overseas Chinese that returned home once restrictions were lifted. “People here really want to shop right now.”

Indeed, South Korean and Japanese brands are also placing a renewed focus on Chinese buyers, who have become the most in-demand in Asia. According to Jeon, the mainland has become the largest market for Korean designers.

“Even during the pandemic, China remains the most influential fashion market in the world,” she said.

The fact that global buyers weren’t able to attend this season is sad, but it’s not a life or death situation for us.

Lee, of EENK, arranged for samples of her new collection to be sent to Shanghai Fashion Week, where she’s hoping to expand the brand’s network of stockists. She currently works with 22 boutiques in the mainland, more than four times the brand’s number of partners in Seoul.

“It’s hard to predict if we could meet a number of new buyers through the new process,” Lee said. “We’ll see how it goes this first season.”

The lull in Chinese travel retail remains a pain point for businesses in both South Korea and Japan, though will welcome Chinese business travellers in November.

“Tourists are still not able to come to Tokyo freely [but it’s] their consumption [that our] designers are wanting,” said Imajo.

He did, however, note that as e-commerce is allowing Japanese shoppers to find luxury items at lower prices (the country has a long history with policy-driven “premiumisation” of luxury goods), local buyers are saving their budgets to support homegrown brands.

Focus Forward

According to Madame Lu, feedback from brands and showrooms taking part in Shanghai Fashion Week indicate that the industry has largely recovered from the challenges faced earlier this year.

“Some aspects of business, like digital channels and consumer relations, are even doing better than before. Younger generations are paying more attention than ever to emerging brands,” she said.

The fact that the event’s WeChat index peaked at 1,162,290, outpacing Paris Fashion Week’s 240,914, points to its growing cache among local consumers.

Looking ahead, the focus for Shanghai’s organisers will be on retail innovation as well as supply chains and sustainability, which Lu hopes will become increasingly significant to shoppers in China.

Street style at Seoul Fashion Week | Photo: Hugo Lee

While circumstances continue to encourage localisation, Tokyo and Seoul are poised to follow in China’s footsteps, by focussing on local talent and becoming stronger fashion ecosystems in their own right. There is not only room for all three fashion weeks to thrive on both a local and global scale, but the brands in their ecosystems will depend on them to do so.

In June, JFWO announced that it will be moving Rakuten Fashion Week from October to August in 2021. The overdue shift will not only buy Tokyo’s designers time to meet with buyers and produce their wares, but will also allow for a greater number of global press and buyers to attend (Tokyo and Seoul’s dates have long overlapped).

Once plans for next year are confirmed (and assuming travel will have picked up by then) the two organisations will help global media and buyers travel more efficiently, said Jeon.

“Since the brands that participate in these two events should also contribute to the growth of the Asian market in the future, I also feel there is a need for strategic cooperation,” she said.

Tokyo’s charm is its chaotic yet cosy mix of cutting-edge culture and tradition — the event should be the centre of the junction.

With this only being the Rakuten’s third season as title sponsor of Tokyo Fashion Week, industry insiders are waiting to see if the e-commerce giant will help brands make a bigger impact in the future.

“It’s not been long since Rakuten took over the crown of the event, plus the novel coronavirus cast uncertainty in the future,” said Tokyo-based designer Mame Kurogouchi. “I think everyone is still taking a wait-and-see attitude.”

According to local talents, fashion week should hone in on Tokyo’s strong suits.

“[Rakuten] Fashion Week does not need to be one of the largest fashion weeks in the world but, yes, one of the most original and attractive,” said Yohei Oki, half of the design duo Shoop, which hosted its live runway show on October 17. “Fashion is part of culture [and it now] has to be reborn.”

Kurogouchi, who frequently shows in Paris, agrees. “Tokyo’s charm is its chaotic yet cosy mix of cutting-edge culture and tradition. The event should be the centre of the junction by offering more than runway shows,” she said, adding that brand selection and events should focus on quality, not quantity, while organisers should take advantage of Tokyo’s historic sites for showcases.

Comme des Garçons and Sacai Spring 2021 | Source: brands

Imajo’s plans aren’t far off. His goal, once the virus infection crisis is alleviated, is to tap into Japan’s soft power by introducing more cultural events around music and food, an idea he has already relayed to sponsors and the government. The fact that Sacai and brands under the Comme des Garçons umbrella — including its namesake label, Junya Watanabe and Noir Kei Ninomiya — opted to show in Tokyo this season over their usual slots in Paris, could start a homecoming trend.

Meanwhile, in Korea, “in order for Seoul Fashion Week to become one of the world’s top fashion weeks, it will have to bring the order hosting process forward [to the end of Paris Fashion Week] and invest heavily in attracting global clients and digitising,” said Low Classic’s Marketing Director Hwang Hyun-ji. The brand chose to forego a runway show and showcased its Spring 2021 collection digitally in July with 247 showroom.

Jeon admits that there’s work to be done, especially when it comes to attracting Korean talents that have gone on to show at the “big four” fashion cities back to Korea.

“To keep those designers coming, Seoul Fashion Week needed to undergo some changes, and we’re taking small steps toward that end,” she said. Considering the global appeal of Korean culture and talent, however, she’s optimistic.

“This year’s Seoul Fashion Week will be something to behold,” she said. “You’ll see that it has come alive again.”

Related Articles:

Shanghai Fashion Week: A Barometer for the World’s Largest Fashion Market

The Future of Tokyo Fashion Week

Can Seoul Fashion Week Turn Buzz into Business?