Running over the ruins of my home: Lahore’s Orange Train | Pakistan News

Lahore, Pakistan – Perching on a hand-woven, straw-seat stool at my uncle Zahid Mehmood’s dimly lit, rented house in the muddy streets of Gulshan Ravi, I am looking through our old family photo albums. It’s like looking at an antique film reel which projects me straight into the past.

“The train rides through my house,” says my 56-year-old uncle, as he counts the windows in a photograph of the six-storey building on McLeod Road that he once called home.

He is speaking of the new, Chinese-backed commuter train line – Lahore’s Orange Line Metro Train – which began construction in October 2015, signalling a new chapter in the Pakistan-China economic friendship and providing an easier, faster commute for the citizens of Lahore.

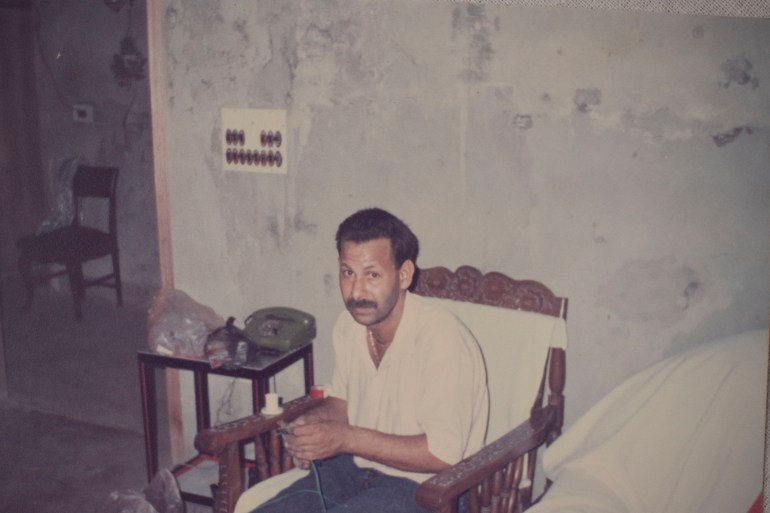

The writer’s uncle Zahid, whose home and business have been demolished to make way for Lahore’s new Orange Train commuter line [Photo courtesy of Anam Hussain]

The writer’s uncle Zahid, whose home and business have been demolished to make way for Lahore’s new Orange Train commuter line [Photo courtesy of Anam Hussain]The house, a pre-Partition structure which he inherited from my Nana along with his six siblings, including my mother, had stood on McLeod Road, right on top of where the new Orange Line train rolls through today. It was demolished in 2017 to widen the road for the new public transportation system.

This house also appears in many of my childhood pictures. In one sepia-tinted photo from 2001, I am 10 years old, standing on the street outside, holding my uncle’s then one-year-old daughter, Aneeqa. I spent every school summer holiday at McLeod Road, and after the six weeks, I would return to the UK where my parents had emigrated in the late 1990s.

And now, here I am, many years later, to follow the train line that runs through my childhood memories.

The writer, aged 10, on Mcleod Road with her cousin Aneeqa [Photo courtesy of Anam Hussain]

The writer, aged 10, on Mcleod Road with her cousin Aneeqa [Photo courtesy of Anam Hussain]‘That train snatched all my earnings’

McLeod Road in Lahore, once a top-notch office furniture market with housing above shops and dozens of old buildings constructed before 1947, now runs along the route of the 27km Ali Town-to-Dera Gujran train line.

The Chinese-backed train, launched mid-pandemic on October 25 this year, boasts a bright colour scheme, reflecting Lahore’s vibrant culture, in shining shades of grey, red and orange. The train – smart and sleek – features glossy white interior walls and grey-with-striking-red, bench-style seating arranged in opposing rows in all five air-conditioned carriages. Hailed as a first for comfortable travel in a city of rough roads, it accelerates smoothly with an operating speed of up to 80km/h (50mph).

A view of the Orange Train and the street below [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]

A view of the Orange Train and the street below [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]Talking about his once-flourishing family furniture business, Wahid & Co, which operated below the McLeod Road house, Zahid says in a broken voice, “I will never set foot on that train, I don’t want to look at it. It snatched all my earnings.”

His wife, Anila, seated next to him, points to her wedding photograph and adds, “I have so many memories tied to this place. I came here as a bride. My children were born here.”

While she understands that it is economically efficient to build transit lines in a developing country like Pakistan, she says, “Not in such a manner that it results in the displacement of people in their own land.”

Shaping growth after a history of neglect

A lack of transport infrastructure has been a constraining factor in the economic development of Pakistan. The Orange Line, with its set of 27 trains, is one of the first modern mass transit systems in the country, aimed at addressing this issue.

“It will make a major difference to congestion in the city and control of traffic flow. Secondly, for the environment, the smog which blankets Lahore – it is a step to help reduce that,” Muhammad Jahanzaib Khan Khichi, provincial minister of Punjab for Transport, tells me when I speak to him as part of my investigation into how the train has affected people’s lives here.

The Orange Train runs over the McLeod Road neighbourhood in Lahore [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]

The Orange Train runs over the McLeod Road neighbourhood in Lahore [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]“If we directly address and connect these two main factors with the citizens of Lahore, I think it is a huge benefit for them. The climate change affecting us is the most threatening [issue] for the people of Lahore,” he adds.

“Since our traffic system is very time-consuming, this train route will save time. People are gradually beginning to use the service,” he says.

It represents one step towards shaping the growth of the second-largest metropolitan city of Pakistan, as the train services awaken after a history of neglect and termination.

After the conquest of Sindh by the British colonial government, Pakistan’s first rail infrastructure became operational in 1861, running between Karachi and Kotri, now the largest city in Pakistan’s Jamshoro District.

In 1964, the first inner-city service opened – the Karachi Circular Railway (KCR). It was used by commuters, carrying as many as six million passengers a year. By the 1990s, unable to withstand the pressures of huge financial losses and a drop in the number of annual passengers, the KCR line shut down. After that, not much was done to upgrade and expand the country’s rail system.

Instead, road networks and motorways became the new symbols of progress, and the number of vehicles on the roads steadily rose. In 1980, the total number of vehicles registered in Lahore was 70,342, rising to more than 1.16 million in 2005, and growing by more than 100 vehicles a day.

The smart new Orange Train in Lahore [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]

The smart new Orange Train in Lahore [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]‘A fantastic initiative’

The new Orange Line, which connects Dera Gujran in the east of Lahore to Ali Town in the western outskirts, has been built as part of the China Belt and Road initiative (BRI) and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Both projects are efforts to reinvigorate infrastructure in Pakistan, which is considered a strong market for Chinese trade, connecting large markets and production centres.

Partially financed by the Pakistani government, the Orange Line operates as a joint venture between China Railway and Norinco International – China’s construction engineering company.

Zeeshaan Shah, founding board member of the privately owned China-Pakistan Investment Company (CPIC), based in London with offices in Karachi and New York, explains that China’s investments in Pakistan are important for the country’s development as an emerging market, and will bring critical infrastructure and provide a more conducive environment for local businesses to grow and thrive.

“The relationship is based on common goals for a peaceful and progressive region,” he says. “One key outcome of this investment is that the country, after suffering from an acute energy shortage for 25 years, is now in an energy surplus. Pakistan generates more electricity today than it requires. This would not have been possible without China.”

“Upgrading the commuter transport network in Pakistan’s second-largest city is a fantastic initiative,” he adds.

At the opening ceremony of the new train line, complete with 26 new stations, Punjab Chief Minister Sardar Usman Buzdar announced that the new transport system would provide an “international standard” of service for the citizens of Lahore.

It certainly looks the part. The welcoming staff wear smart uniforms – a black suit with an orange ribbon on the cuffs, a matching orange tie and a hat with an orange band for the men; a traditional navy shalwar kameez combined with a bright orange scarf that complements the train’s exterior for the women.

Neatly dressed and professional, Orange Train staff greet commuters [Asad Amjad/Al Jazeera]

Neatly dressed and professional, Orange Train staff greet commuters [Asad Amjad/Al Jazeera]The train has mostly been welcomed by Lahore’s residents. On its opening day, 50,000 people took a ride, growing quickly to an estimated 250,000 commuters who are using it daily now. The train is expected to reduce congestion on Lahore’s busy roads as a result. While it is too early to say by how much, previous initiatives to move people out of cars and onto public transport have been successful. In 2013, the first rapid-transport bus system – the Lahore Metro Bus – began operating. It now carries nearly 180,000 passengers a day and a study by the Sustainable Development Centre at Lahore’s Government College University in 2016 found that road congestion had reduced markedly along the route of the bus.

It is cheaper to travel by train than by road, as well. Tickets for the new train are 40 rupees (around $0.25) for a one-way journey of up to 27km (16.7 miles) along the route. By contrast, the Uber fare per km is 10.67 rupees ($0.07) – nearly 290 rupees ($1.82) for a 27km taxi ride.

Daily commuters using the train can expect to spend approximately 2,400 rupees ($15.08) a month for their return journeys – about 13 percent of the average national monthly wage of 18,754 rupees ($117.82).

Such has been the general approval surrounding the launch of the Orange Line train, Pakistan Railways now also hopes to get the Karachi Circular Railway back on track, after 21 years of disuse, by the end of this year.

But while the 300bn rupees ($1.8bn) train line is expected to save ordinary people more than 60 billion rupees ($377m) a year in travelling costs, local communities and owners of businesses living and working alongside the route say the cost to them could be just as high.

Shahbaz Sharif, right, then-Chief Minister of Punjab province, cuts a ribbon as he inaugurates the first test run of Orange Line Metro Train, in Lahore, Pakistan on May 16, 2018 [File: Rahat Dar/EPA-EFE]

Shahbaz Sharif, right, then-Chief Minister of Punjab province, cuts a ribbon as he inaugurates the first test run of Orange Line Metro Train, in Lahore, Pakistan on May 16, 2018 [File: Rahat Dar/EPA-EFE]When the bulldozers came

At the height of demolition work to make way for the new train, at the end of 2016, a dozen structures a day were being bulldozed by the Lahore Development Authority (LDA). These had been marked for destruction the year before. As well as business premises and people’s homes, heritage sites were demolished – including the mosque and courtyard attached to the 455-year-old Mauj Darya shrine – and more than 600 trees were cut down to make way for the new electric network.

Under a British colonial-era law, the Land Acquisition Act of 1894, the Pakistani government has the right to acquire private property for public purposes in exchange for paying compensation to those whose land is needed.

“When we first received the notice in 2015 that our house lay within the proposed Orange Train route, we thought it was some false information,” says uncle Zahid. “It was when we got the second notice, things got serious.

“We managed to obtain a stay order until the end of 2016 for the demolition of our home and shop. But once that expired in 2017, the people from the Lahore Development Authority arrived in the first week of January and began to knock down our main gate. They gave us three days to pack up, disconnected our gas and electricity supplies and forced us to leave on January 9, 2017.”

The remains of the writer’s family home on McLeod Road, demolished to make way for the Orange Train [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]

The remains of the writer’s family home on McLeod Road, demolished to make way for the Orange Train [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]One year after the demolition of their home and business, the family received compensation of just less than 20 million rupees ($126,460), but Zahid says the house and shop were worth closer to 50 million rupees ($316,150) before the Orange Train rolled in.

Zahid and Anila packed up their three children, aged 17, 15 and 11 at the time, boxes and furniture, with little idea of how they would keep a roof over their heads. The compensation they had received – which had to be shared with Zahid’s other siblings who co-owned the property – would not stretch to a family-sized home to replace it. They say they are thankful to other relatives who helped out and allowed them to stay with them for a couple of months before they moved to their current rented house about 15 minutes’ drive from their old home.

The writer’s mother, her uncle Zahid, and their siblings with their parents in Lahore when the family home was still standing [Photo courtesy of Anam Hussain]

The writer’s mother, her uncle Zahid, and their siblings with their parents in Lahore when the family home was still standing [Photo courtesy of Anam Hussain]From running a successful and growing family furniture business attached to an ancestral home, Zahid is now working for low daily wages, selling household cleaning materials door-to-door – although even this has become patchy due to the pandemic lockdowns – residing in a small temporary house close to the Gulshan Ravi Orange Line train station. He, along with others, does not feel the compensation paid was enough.

Zafar and Associates, a law firm based in Lahore, says that compensation paid for the forced acquisition of land needed for public purposes must be “adequate”.

“The principles laid down for the determination of compensation, as clarified by judicial pronouncements made from time to time, reflect the anxiety of the law-giver to compensate those who have been deprived of property, adequately enough in the sense that they are to be given gold for gold and not copper for gold,” states an explanation of the law on the firm’s website.

However, Muhammad Jahanzaib Khan Khichi, the provincial minister, claims that the government of Punjab has compensated owners of demolished buildings in full. “The land and property issues have been resolved and businesses affected were offered an alternative (the compensation),” he says

After the bulldozers left, all that remained of the family home on McLeod Road was a 9 square metres (100sq foot) area of land. But Zahid says there is not enough money or space to rebuild his broken life on that.

The old hilly path to the house [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]

The old hilly path to the house [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]A place we once called home

After I finish flipping through to the very end of the photo albums at my uncle’s house, my mother and I set out to walk along McLeod Road, to see for ourselves what has happened to the place we once called home.

After a short ride by Uber taxi from Gulshan Ravi train station, past the four-pillar Mughal-era monument, Chauburji, through the historic old Anarkali bazaar and alongside the colonial architecture of the General Post Office, we arrive at McLeod Road, a commercial area which now lines up alongside the tunnel through which the train track runs. The next station on from here is Lakshmi Chowk, further to the east.

The Chauburji-Mughal era monument in Lahore, next to the elevated railway [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]

The Chauburji-Mughal era monument in Lahore, next to the elevated railway [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]We find ourselves sandwiched between the bridge-like train passage and the high walls of the King Edward boys’ hostel for university medical students, one side of the tracks racing towards Ali Town and the other towards Dera Gujran.

We see, on the left side of the tunnel, the slightly hilly path that leads to the site of the old house. It reminds me of the days, 20 years ago, when my uncle would ride his blue Vespa scooter down this hill.

We continue walking along the steep hill until we reach a furniture shop on the other side of where our family’s old house once stood. A chair-maker, whose shop was not directly on the Orange Line route, enquiries about why we are here looking at a broken structure. He is in his 50s and dressed in a scruffy brown shalwar kameez.

Upon learning why we are here, he says he is appreciative of our visit. “If you spend a little, you can re-build a smaller version of the shop,” he encourages us.

Stepping over the debris of what was once my childhood home, I hold back tears. Only half of the long staircase, which once led to the rooftop where I played in the rain and from which I flew kites, remains. The strongest side pillars are still intact, surrounded by rubble.

On the wall of the old hilly path reads a sign ‘Office furniture wholesale market’ [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]

On the wall of the old hilly path reads a sign ‘Office furniture wholesale market’ [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]Next to Zahid’s shop, a 10-minute walk from the site of the new Lakshmi Chowk station on the Orange Line, there used to be two workshops belonging to brothers Shuja Shahid and Sheikh Khalid. They sold office chairs and tables. Fortunately, they live on the outskirts of Lahore, and so their homes survived. But their businesses, here, were wiped out.

“For us, the Orange Train is a symbol of loss, operating in a country which runs against the interests of the many and in the interests of the few,” says Khalid, who is standing with other shop owners, discussing the loss of their businesses. The street they are gathered in houses food stalls and old, abandoned cinema houses that serve as a reminder of the glorious days of Punjabi films.

Shahid, who says he has been unable to re-start his business elsewhere, adds, “I am angry they did this to us. Our business can’t be the same again.”

Razia, a mother in her 30s, lives five minutes’ walk from Lakshmi Chowk station and says she feels more positive about the new train line. She says she looks forward to taking rides with her family just for the fun of it – a popular pastime in Pakistan known as “joyriding”. She is happy that her family’s house lies just off the other side of the main road, and therefore, avoided destruction. It has not suffered a decrease in value, either.

“Thank God, we had no issues with the train route passing through our area. Whereas those closest to the route were negatively affected and saw their property values decrease.”

Across the city in 45 minutes

For those whose properties have not been demolished here, business continues much as usual. The owner of the famous Butt Sweets and Bakers – located a little further east up McLeod Road – tells me, “We have not noticed any changes. Everything remains the same for us.” In fact, she adds, the train may even bring in new customers as it offers a new way to travel across the city.

Opposite the train tunnel, running alongside McLeod Road, is Hall Road – a street known as the largest electronics market in Pakistan.

Tahir Javed Rathor, 45, sells and repairs all kinds of LED TVs here. He has been commuting here every day ever since he opened his business more than 20 years ago and now uses the train, getting on at Thokar Niaz Baig station close to his home in southeast Lahore. He is delighted that his commute time has been cut dramatically from more than an hour each way before the train line opened to just 20 minutes.

“It is much cheaper to pay for an 80 rupee ($0.50) return ticket on the train than to pay fuel prices to travel in our car. Before, it cost me between 600 and 1,000 rupees ($3.77-$6.28) each day to commute.

“Even my customers are using this service now. I am happy the line passes near this road, both the Lakshmi Chowk station and the General Post Office stations are close to me, connecting travellers to the electronics hub,” he says.

A view of the Orange Train from Mcleod Road [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]

A view of the Orange Train from Mcleod Road [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]Despite the pandemic and social distancing advice issued by the government, large numbers of people are still cramming on to the train, eager and excited to experience it. Wearing a face mask is mandatory, but there is no social distancing to speak of on board.

Many of those already using the train are lower-middle-class workers, who live and work in different parts of Lahore and find it a cheaper and faster alternative to commute from one end of the city to the other in just 45 minutes. Others use the train for pleasure.

With two stations underground and others built on an elevated structure, above street level, passengers enjoy plenty of aerial views of the capital of Punjab province and its nearby heritage sites. The royal dimensions of the 16th-century Shalamar Gardens become clear from the new vantage point offered by the passing train.

Shahbaz Sharif, then-Chief Minister of Punjab province, waves from onboard the Orange Line train during the unveiling ceremony of the first set of bogies of Lahore Orange Line Metro Train, in Lahore on October 8, 2017 [File: Rahat Dar/EPA-EFE]

Shahbaz Sharif, then-Chief Minister of Punjab province, waves from onboard the Orange Line train during the unveiling ceremony of the first set of bogies of Lahore Orange Line Metro Train, in Lahore on October 8, 2017 [File: Rahat Dar/EPA-EFE]‘Dustbins should be installed’

Amna Khalid, 22, has got on the train at the Mehmood Boti station at Darogha Wal in east Lahore to travel to the last station at Ali Town and then back again. Like lots of passengers, she is just taking the journey for fun. Amna is a writer and was one of the first to use the service to make a video review of it for her YouTube channel which has thousands of subscribers.

While she walks the length of the train looking for a seat, she pulls out her selfie stick to record videos with her brother Ghulam, 18, who is accompanying her on her joyride. He adds a little humour to the proceedings, “We are now on the train to Dubai!”

With cameras dangling from their necks and selfie sticks in their hands, many young passengers around us are similarly sharing their Orange Line experience on their social media accounts.

“Taking a ride on this train, it was my first time using an automated ticketing machine. This is the most affordable and the best possible transport system because it is so fast,” says Amna. She does worry about the amount of electricity required to power the train, however, and fears the ticket price will rise in the future. “This train consumes up to 1.35 million units of electricity every day,” she adds.

Lahore and a view of the Orange Train [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]

Lahore and a view of the Orange Train [Moeez Javed Rizvi/Al Jazeera]Another passenger, Malik Nazir Ahmed, 65, a retired section officer at the Punjab Civil Secretariat and a resident of Allama Iqbal Town in southwest Lahore, worries the electric train could increase the incidences of power cuts in his area.

Although the country does now have a surplus of electricity and power cuts are not as frequent as they once were, they do still occur, particularly in the hot summer months when more power is needed for air conditioning units, fans and refrigeration.

“The government should consider switching from using grid electricity to a solar-powered train system like is being trialled in the UK,” he says. Meanwhile, his wife, Rahat Samina, 60, worries about littering by commuters. “Dustbins should be installed,” she says.

Home again

Arriving back at Gulshan Ravi’s Moon Market which leads to my uncle’s rented house, we are welcomed by neatly organised stalls of fruit and vendors preparing syrup-sweet coils of deep-fried Jalebi, a traditional sweet in Pakistan.

Back home, my cousin Aneeqa, now 20, serves us tea. She is less concerned about the loss of her childhood home; instead, she says, she looks to the future.

The train ride from Ali Town to Dera Gujran is an “absolute dream” for a student like her – she will soon be starting university. “I would love to travel on the train to university instead of taking the bumpy rickshaw ride like I do to school,” she says while distributing the super-sticky Jalebi we bought on our way. The train will be cheaper, too, she says.

As we sip the warm milky drink, uncle Zahid sketches out possible ideas to rebuild the shop-house combination in the remaining 9 square metres (100sq feet) of space on McLeod Road. He is coming around to the idea of starting over. It won’t be like their life before – and he says he will never be persuaded to ride on the Orange Line train – but it might be something.

The Jalebis the writer enjoyed after her trip on the Orange Train [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]

The Jalebis the writer enjoyed after her trip on the Orange Train [Anam Hussain/Al Jazeera]With the help of the architectural features which remain visible in the old photographs, he reckons that if he could one day construct a small-scale version of what was once on McLeod Road – he and his family might be able to support themselves again.

“It will stand as a symbol of our family history,” he says. “Thanks to these photographs. They trigger memories and future inspirations in a way nothing else can.”