Richemont Needs a Transformational Move

Covid-19 has been tougher on Swiss luxury group Richemont than on French rivals Kering and LVMH, and this week its shareholders are being asked to bet on the company’s future.

On Tuesday, November 17, in a bid to preserve cash after halving its dividend to one Swiss franc per share, the Geneva-based conglomerate will ask shareholders at an “extraordinary” meeting to approve the creation of 22 million new shares. The initiative is something of a loyalty programme. By issuing tradable warrants that entitle holders to acquire new Richemont shares in three years at a fixed price, it allows backers the opportunity to benefit from potential post-pandemic upside.

But the group’s troubles go beyond the pandemic.

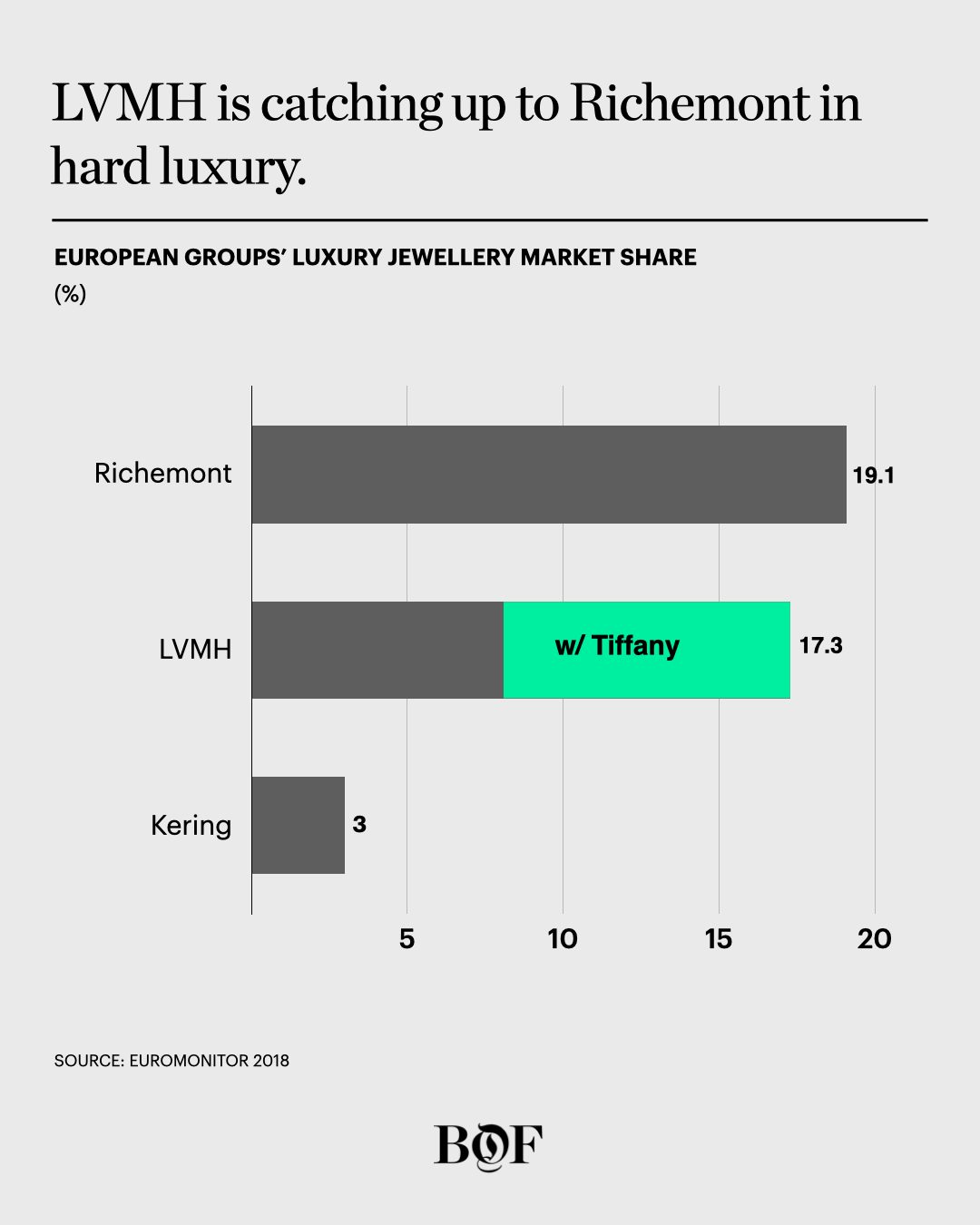

For years, Richemont — which owns a stable of “hard” luxury brands such as Cartier, as well as the fashion houses Chloé and Alaïa and the luxury e-commerce giant Yoox Net-a-Porter Group (YNAP) — relied on hefty profits and steady growth to keep investors happy, if not enthused. But more recently, LVMH and Kering, long the dominant players in “soft” luxury, have strengthened their positions in watches and jewellery, challenging Richemont’s core. LVMH, which acquired Bulgari in 2011 and is set to acquire Tiffany, is a particular threat.

LVMH Richemont Kering

The added pressure, plus existing trouble with sales of watches in the $1,000 range, disrupted by the rise of the Apple Watch, as well as underperformance in both fashion and its online division, where YNAP has suffered hundreds of millions of dollars in losses since Richemont fully acquired it in 2018, have put the group in a weaker state than ever before.

Presently, Richemont shares are trading at less than three times its annual revenue, far behind LVMH, Kering — which are trading at over four times revenue — and Hermès, which is trading at 15 times its yearly sales.

To boost investor confidence, Richemont must make a truly transformational move.

A NEW E-COMMERCE ALLIANCE

It’s uncommon for Richemont’s executive chairman Johan Rupert — who owns less than 15 percent of the group’s shares but controls over 50 percent of the voting rights on the board of directors — to show up for the Swiss luxury group’s mid-year results meeting. Sometimes, he doesn’t even make the full-year proceedings. But November 6, 2020, was a big moment for the company. After all, just a day earlier, Farfetch, Alibaba and Richemont had announced a game-changing joint venture to better reach China’s luxury consumer online.

“This is not some land grab or power grab,” he said of Richemont’s tie-up with the Chinese tech giant and the online luxury marketplace, which he characterised as “a hybrid platform that will be attractive for all partners.”

Rupert has extolled the virtues of a neutral, shared platform before, most notably in 2015 at the Financial Times Business of Luxury Summit, when he invited luxury industry leaders to join a “neutral” platform on which all brands could operate their online businesses.

“Yoox on its own, Net-a-Porter on its own, Richemont on its own — and I said to [LVMH Chairman and Chief Executive Bernard] Arnault the other day, ‘Forget it!’ — LVMH on its own. We’re not big enough,” he said. “I was speaking to him, as I’ve spoken to Kering, about joining us on that platform, to make it totally neutral. It’s too big a game for any company to try to dominate.”

At the time, Rupert was betting on the soon-to-be-formed YNAP, not Farfetch. Rupert claims that his shifting interests aren’t a reaction to performance at YNAP, though the company has lost its sector-leading position, allowing competitors like MatchesFashion and Farfetch, now the frontrunner in luxury e-commerce, to gain market share.

“YNAP will remain important to us and important to its other clients in selective distribution,” he said. “Please get out of your mind that it’s because we’re disappointed with YNAP.”

But the decision to back YNAP’s arch-rival reflects a new reality. While Net-a-Porter and Mr Porter may remain top retail brands in the eyes of the luxury consumer, the group is no longer the leader in the space.

As part of the deal, Richemont and Alibaba are pouring $550 million each into Farfetch, with Artémis — the family office of the Pinaults, who control Kering — adding an additional $50 million. The $1.15 billion will help jumpstart an initiative in which Farfetch will open shops on Alibaba’s luxury site Tmall Luxury Pavilion, outlet store Luxury Soho and its cross-border marketplace Tmall Global.

Not only will the brands and independent retailers that sell via Farfetch’s marketplace benefit from such an arrangement, but the partners hope that more brands will use Farfetch’s white-label technology to build their own e-commerce sites, both in China and abroad, expanding into a space once dominated by Yoox, which used to power the back-end e-commerce technology for brands including Kering-owned Bottega Veneta, Balenciaga, Saint Laurent and Alexander McQueen, as well Moncler and Diesel, among others. Over the years, brands defected from the platform to manage e-commerce themselves — and some have partnered with Farfetch on certain elements of the business.

Rupert’s decision had the confidence of his investors — Richemont shares rose seven percent on early Friday morning trading after the announcement. Analysts at Bernstein, for instance, changed the group’s rating to “outperform” after the news of the venture broke.

But the game-changing move may be for Rupert to relinquish full control of YNAP.

While Rupert was quick to defend YNAP in the wake of the Farfetch investment, he didn’t rule out offloading it from Richemont’s books, saying that he was “never hellbent on owning 100 percent” of YNAP.

“We’re not big enough or tech-savvy enough to do this on our own,” he added. Rupert also said how YNAP and Farfetch complement each other, never ruling out a merger.

“YNAP was started by people who love the fashion side and gave a curated view for a very loyal clientele. Farfetch started from the tech side,” he said. “I don’t think you can have a proper omnichannel business without that. Richemont gives a brand point of view.”

Could Richemont sell the majority of YNAP to Alibaba or Farfetch?

“It makes more sense for Richemont to sell YNAP to Alibaba,” said Elsa Berry, founder of managing director of Vendôme Global Partners. “Alibaba has the strategic depth.” However, a partnership with Farfetch would give the online marketplace what it has long lacked — strong consumer retail brands in the form of YNAP’s Net-a-Porter and Mr Porter units — while Farfetch’s superior technology and logistics could help solve some of YNAP’s biggest problems. Either scenario would accelerate the industry consolidation analysts have been predicting for years.

“It would be an ideal way out for all parties concerned,” said Luca Solca, an analyst at Bernstein. “So, not too far fetched, I would say.”

EXIT FASHION, FOCUS ON HARD LUXURY

Richemont could also exit the soft luxury sector, where it trails rivals, and refocus on its watches and jewellery core. While Richemont has owned fashion brands for decades, it has never managed to scale those businesses in a similar way to hard luxury — which generates the majority of the company’s profit — and in turn, they now lag far behind their competitors. In its most recent fiscal year, the group’s “other business” category, which includes Chloé, Alaïa, Dunhill, Montblanc, American sportswear line Peter Millar, gunmaker Purdey and Italian handbag Serapian, accounted for just €1.8 billion, or 13 percent, of its overall sales. A decade ago, the same collection of businesses — which were then split into two groups — generated €1.3 billion in annual sales. That’s 38 percent growth, small compared to LVMH’s fashion and leather goods division, which saw sales increase 194 percent over the same period.

Chloé, now led by up-and-comer chief executive Riccardo Bellini, who previously led Maison Margiela, was once on track to become a billion-dollar brand. However, creative director Natacha Ramsay-Levi has not found traction in accessories, where predecessor Clare Waight Keller was particularly savvy, and rumours have swirled for years that she will be replaced. The brand’s executives have also been stymied by the advancements of its rivals in competing groups, which are vertically integrated, better funded and have the negotiating power to secure the best retail real estate and maintain the best positioning on department store floors. Chloé’s US business was deeply affected by the bankruptcy of Barneys New York, one of its main distributors in the region. The store never repaid the nearly $1 million it owed the brand.

Alaïa, a jewel of a label whose unwavering identity under late designer Azzedine Alaïa made it highly coveted by an elite group of consumers, has suffered from the same restrictions. In 2017, 10 years after Richemont had acquired the Parisian house, the company opened a 6,000 square foot store on London’s New Bond Street. Previously the group had opened a three-storey Alaïa flagship in Paris to further reduce the brand’s reliance on the increasingly tricky wholesale channel, launched online sales with Net-a-Porter as well as on its own channel, and began developing a beauty business with Shiseido. But those efforts, which helped the business inch north of €50 million in annual revenue by 2017, have been incremental. However, under the right steward, the house codes — form-flattering engineered knits, punch hole eyelets, sleek black — could be leveraged to significantly broaden the label’s appeal.

In 2017, Richemont did begin to prune its fashion portfolio, selling Hong Kong fashion label Shanghai Tang that year and leather bag maker Lancel in 2018. It’s going to be harder than ever to sell its current portfolio. Dunhill, once led by star creative director Kim Jones, has struggled to find relevance. But Chloé and Alaïa may be of interest to potential acquirers.

Investors would certainly like to see Richemont solely focused on fine jewellery, a pandemic-era win, and watches, a category that is bifurcating. On the lower end, watches are on the decline, with the Apple Watch and smartphones all-but eliminating the lower end of the high-end market. But collectable watches remain in demand.

While investors believe Richemont missed a big opportunity to acquire Tiffany — which would have cemented the group’s category dominance — a smaller, more profitable business would be good for shareholders.

A STRATEGIC MERGER

For years, analysts have suggested that Richemont could sell itself to Kering, Chanel or Hermès to form a larger group that could truly go up against LVMH, which is so diversified in its portfolio, so big, that it is nearly untouchable and wields a notable amount of control over the industry at large.

Kering is considered to be Richemont’s most likely partner. “From a strategic point of view, it makes sense to put the two together,” said Mario Ortelli, a luxury advisor. “One group has a stronghold in soft luxury, the other in hard luxury. If Mr Rupert has the mind, anyone will be more than happy to listen to him and try to find a way to make it work.”

If Kering chief executive François-Henri Pinault was able to carve out a role for Rupert, it could be a win-win for everyone, allowing the combined entity to defend itself better against LVMH.

However, according to Rupert, such an arrangement remains out of the question. “It’s not for sale and it’s never been for sale,” he said last week. “We are not interested in mergers. We have already cooperated in terms of eyewear. We’re prepared to do deals as long as they make commercial sense. We don’t have, like some of our competitors, mortal enemies.”

Many analysts agree that the core business is strong enough to stand alone and doesn’t require a strategic partnership, even if it would be a nice-to-have.

“The first priority should be to fix Richemont and its perimeter: get out of online retailing, and get out fashion and leather goods,” Solca said. “Cartier, Van Cleef and the watch brands can remain stand-alone, like Chanel and Hermès — no urgent need to merge, I believe.”

However, while Rupert may not need to sell now, executives who have worked with him in the past say he loves a deal. As LVMH’s position in hard luxury strengthens, and he inches closer to full retirement, he needs to plot out the future of the business — not only for its survival but also for the preservation of his own fortune.

AN EXECUTIVE SHAKEUP

For months, analysts, investors and media alike have been speculating that Richemont group chief executive Jérôme Lambert might be relieved of his duties after two years on the job to be replaced by Cyrille Vigneron, the well-liked and successful chief executive of Cartier, who has worked with the company on and off for nearly two decades. Some have suggested more recently that there are other candidates in the running, and that the appointee is a woman.

Yet there was no announcement of a management shakeup during the mid-year earning’s call, and the company spokesperson said in a statement to BoF that it does not comment on rumours. What’s more, it’s unlikely that the exit of Lambert, another long-time Rupert deputy, would sufficiently change the dynamics of the business. Vigneron and Van Cleef & Arpels chief executive Nicolas Bos already report directly to Rupert, despite the fact that he is not involved in the business day-to-day. What investors would like to see is a more traditionally managed group with a group chief executive with decision-making power. Before Lambert’s appointment, the company was run for a short time by executive committee, and before that, executive leaders who had Rupert’s utmost trust to manage operations while he served as brand steward. For years, brands were required to bring all of their marketing and advertising materials to quarterly board meetings for Rupert to sign off on them, according to former executives.

“It’s an unstable situation,” one investor, who wished to remain anonymous, said.

This structure has become increasingly untenable and Rupert has stepped further away from the day-by-day activities of the business, which operates out of Geneva. “I don’t think that this management is agile or forward-thinking,” Berry said. “They’re very defensive of their two core businesses at a time with Covid when they need the opposite.”

What’s more, the 70-year-old has not publicly laid out a succession plan. Most of his children are not involved in the business and while his son, Anton Rupert, was named a non-executive board director in 2017, it seems unlikely that he will be called upon to lead the business any time soon.

As Ortelli said, “The only one who has the answer is Johann Rupert.”

Additional reporting by Robert Williams.

Disclosure: LVMH is part of a group of investors who, together, hold a minority interest in The Business of Fashion. All investors have signed shareholders’ documentation guaranteeing BoF’s complete editorial independence.

Related Articles:

What the Farfetch-Alibaba-Richemont Mega-Deal Means for Luxury E-Commerce

Richemont’s Fashion Business: A Health Check

Yoox Net-a-Porter’s ‘Painful’ Tech Upgrade Drags Down Richemont