Post Corona: From the Brand Age to the Product Age | Opinion

At my first firm, Prophet, we roamed the world preaching to Global 500 companies that a firm’s ability to provide above-market returns depended on their ability to develop a compelling brand identity, and then treat this ID as a religion, nodding to the identity with every action and investment. And the way that was done was through the awesome power of broadcast advertising.

From the end of World War II until the introduction of Google, the gangster algorithm for shareholder value was simple: create an average, mass-produced product and infuse it with intangible associations. You then reinforce those associations through cheap broadcast media, which occupied the average American for five hours a day. The Brand Age grabbed the baton from an out-of-breath manufacturing sector. Firms like McKinsey, Goldman Sachs, and Omnicom built the workforce and infrastructure for a booming services economy. The Brand Age created gurus, marketing departments, and CMOs, and kept black town cars lined around the headquarters of Viacom and Condé Nast. Emotion injected into a mediocre product (American cars, light beer, cheap food) was the algorithm for creating hundreds of billions in stakeholder value. Kodak moments and “teaching the world to sing” translated to irrational margins based on an emotional response to inanimate products.

Don Draper lived the high life. The ad business saw creatives who dyed their hair in their forties and wore cool glasses as the messiahs of the last half of the twentieth century. The ad industry brought brand to washing machine and minivan manufacturers. Brand was a new kind of pixie dust that offered an exceptional lifestyle to average businesspeople. Believers in the advertising industrial complex would be blessed with sacrosanct margins despite products void of differentiation.

I made a nice living preaching this. And then… the internet.

I sold my stake in Prophet in 2002. I had started hating the services industry. Success in the services industry is a function of your ability to communicate ideas and develop relationships. I loved the former and despised the latter — managing colleagues and being friends with people for money. The services industry is prostitution, minus the dignity. If you spend a lot of time at dinners with people who aren’t your family, it means you’re selling something that is mediocre.

I got lucky and got out. The Brand Age was drawing to a close. There’s no one moment, but a series of opportunistic infections: Google, Facebook, and technology that liberated the affluent from ads. If you want to mark the beginning of the end, you could do worse than Tivo. Launched, fittingly, in the last few months of the twentieth century, Tivo allowed those with extra disposable income to trade it for something even more valuable: their time. Once you owned a Tivo, with just a little patience and prior planning, you never had to watch a commercial again. Advertising became a tax that only the poor and technologically illiterate had to pay.

Just as Tivo was giving us a preview of a world without commercials (at least for those who could afford it) a slew of other new products were coming along that were ridiculously better than what we used before (Google vs. classified ads, Kayak vs. travel agents, Spotify vs. CDs). They don’t need to interrupt Succession every ten minutes.

If Tivo marks the beginning of the shift from the Brand Age to the Product Age, the summer of 2020 saw the Brand Age’s end.

If Tivo marks the beginning of the shift from the Brand Age to the Product Age, the summer of 2020 saw the Brand Age’s end. When the killing of George Floyd and subsequent protests briefly displaced the pandemic in the front and centre of our national consciousness, making obvious the passing of the Brand Age’s into history. Seemingly every brand company did what they always do when America’s sins are pulled out from the back of the closet where we try to keep them hidden: they called up their agencies and posted inspiring words, arresting images, and black rectangles. Message: We care. Only this time, it didn’t resonate. Their brand magic fizzled.

First on social media, then tumbling from there onto newspapers and evening news, activists and customers started using the tools of the new age to compare these companies’ carefully crafted brand messages with the reality of their operations. “This you?” became the Twitter meme that exposed the brand wizards. Companies who posted about their “support” for Black empowerment were called out when their own websites revealed the music did not match the words. The NFL claimed it celebrates protest, and the internet tweeted back, “This you?” under a picture of Colin Kaepernick kneeling. L’Oréal posted that “speaking out is worth it” and got clapped back with stories about dropping a model just three years earlier for speaking out against racism. The performative wokeness across brands felt forced and hollow. Systemic racism is a serious issue, and a 30-second spot during The Masked Singer doesn’t prove you are serious about systemic racism. That’s always been true, about ads on any issue, but social media and the ease of access to data on the internet has made it much harder for companies to pretend.

Welcome to the Product Age

Paying lip service to social causes is a sideline for brand builders, of course, but these same tools are damaging the core business as well. In the Brand Age, a wealthy traveler new in town tells his cabdriver to take him to the Ritz, because that’s the brand he knows. In the Product Age, this valuable customer checks her phone as she gets off the plane, learns that the Ritz is being renovated, and that reviewers believe it’s overpriced, and she crowdsources a recommendation for a new boutique hotel in a hipper neighbourhood.

The losers in this transition are the media companies that provided platforms for the big and bold brand-building advertising of the Brand Age, and the creative-driven ad agencies that made them. If you make your living on the back of 30-second spots featuring award-winning ad copy and talented actors connecting emotions to products, this is not the future you were hoping for. Twenty years ago, Levi Strauss & Co. asked three outside advisers to sit in on their board meetings: two advertising agency icons, Lee Clow and Nigel Bogle, and yours truly, the brand strategist. That’s how important creativity and advertising was to the company. I’ve been in perhaps 150 board meetings since those Levi’s days, and I don’t think I’ve heard a director ask what the ad agency thought about anything. Their time has passed.

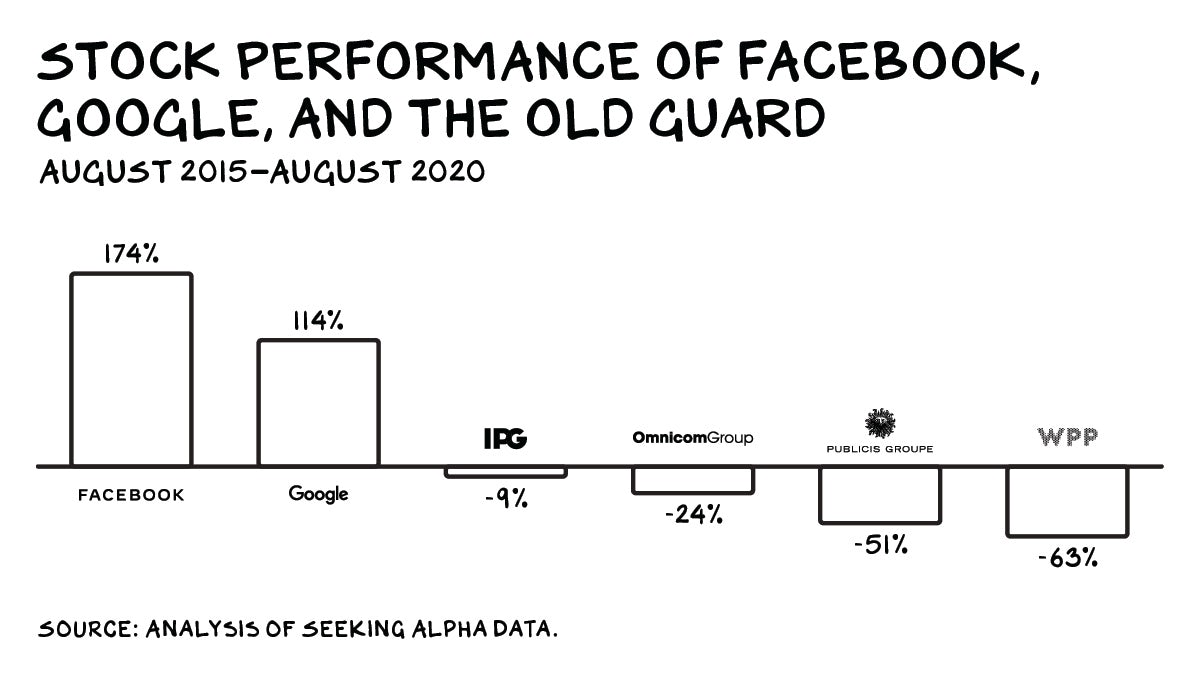

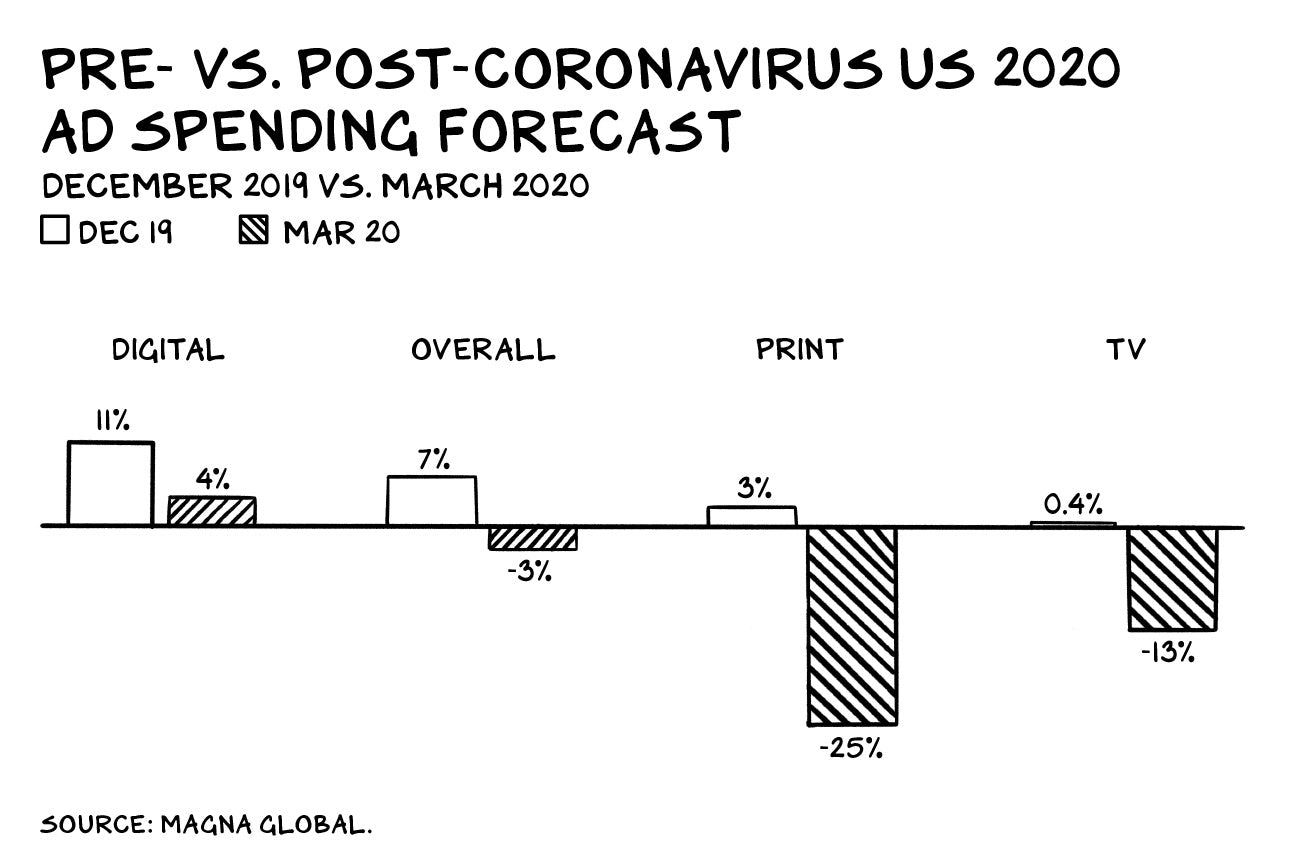

Troubled economic times always mean a pullback in ad dollars, and that is initially affecting the online and traditional players. Search terms and ads on Google and Facebook plunged 20 percent in the month after George Floyd’s killing. But the pullback in traditional media was even steeper. The recovery will be equally bloody. Because when the tide comes back in, it will flow only to the advertising media of the Product Age, not the old guard of the Brand Age. The Google-Facebook duopoly’s share of the digital ad market is predicted at 61 percent in 2021.

In 2012, I was doing work with the Four Seasons. Great firm — nice people, Canadian (redundant). During the Great Recession, the luxury hotel brand had to cease all print advertising as revenue per room had declined 25 percent. And a strange thing happened when demand returned: the absence of print marketing didn’t seem to make any difference. Multiply this phenomenon by a million, and you have what will happen — thousands of the biggest advertisers globally are about to use this forced abstinence from broadcast media (with business down 30 to 50 percent) to kick the habit, and never return.

The two largest radio firms, iHeartRadio and Cumulus Media, will likely be Chapter 11 (again) by summer 2021. Radio advertising is projected to decline 14 percent in 2020. Covid-19 has a mortality rate of 0.5 to 1 percent in the US. Among US media firms, the death rate will be ten times higher. Firms ranging from Condé Nast to Viacom have furloughed and laid off people as Facebook and Google have ramped up hiring. How do you identify the best people at News Corp, Time Warner, and Condé Nast? Simple, they will soon be working at Google.

Even harder hit are the digital marketing firms that aren’t Facebook or Google. BuzzFeed and Yelp have seen display ads on site decline 40 to 70 percent in 2020 vs. 2019 and are in the ICU. Vox, HuffPo, and Vice will follow. Some will make it out. Some.

Excerpted from Post Corona: From Crisis to Opportunity by Scott Galloway, in agreement with Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Scott Galloway, 2020. Scott Galloway is a professor of marketing at New York University’s Stern School of Business, and a speaker, author, podcast host and entrepreneur.