Other deaths linked to B.C. Aboriginal agency running group home where Indigenous teen died

The B.C. agency responsible for the group home where Cree teen Traevon Chalifoux-Desjarlais died has seen the deaths of at least four other Indigenous youth in its care or aged out of its care, CBC News has learned.

Xyolhemeylh, or Fraser Valley Aboriginal Children and Family Services Society, has faced criticism in the past for inadequate staffing and resources to support vulnerable youth, including in a Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) audit published earlier this year.

Xyolhemeylh is an agency delegated by the ministry as part of an initiative to give Indigenous communities more control over child welfare.

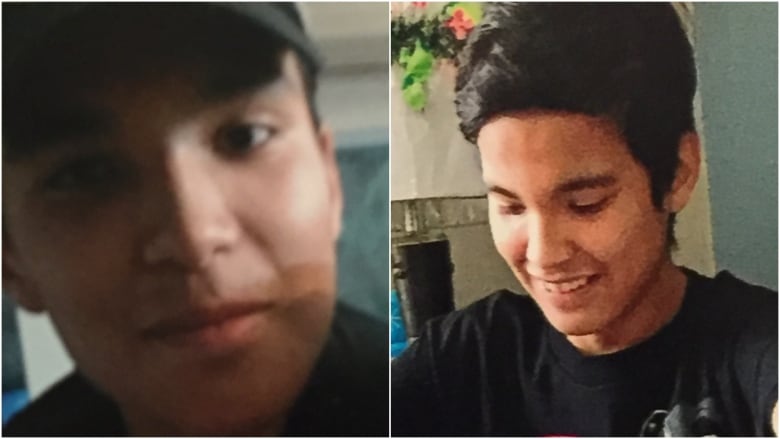

Traevon, 17, died on Sept. 18 in an Abbotsford, B.C., group home called Ware Resource, operated by Rees Family Services, a company contracted out by Xyolhemeylh.

His body was found in a closet in the group home four days after his death.

Others who died aged 2 to 19

Alex Gervais, an Indigenous teen who took his own life in 2015, was also in the care of Xyolhemeylh when he died, according to Doug Kelly, one of Xyolhemeylh’s founders and president of Stó:lo Tribal Council.

Gervais was moved to a hotel room where he was living by himself in violation of provincial government policy. Before his move to the hotel, his group home, run by A Community Vision and contracted out by Xyolhemeylh, was shut down due to unsafe conditions.

Another Indigenous teen with fetal alcohol syndrome, who CBC News is not naming, died suddenly in 2019, just seven months after aging out of care with Xyolhemeylh at age 19, according to documents obtained by CBC News. Advocates such as B.C.’s Representative for Children and Youth have long said child welfare agencies need to be more proactive in creating a comprehensive plan to help youth transition out of care.

Santanna Scott-Huntinghawk also died at 19, just seven months after aging out of care with Xyolhemeylh. She died alone in a tent in Surrey, B.C., in late 2016.

Her sister Savannah Scott-Huntinghawk confirmed to CBC News that she had been with the same agency before losing all her supports after turning 19, in a case that highlighted concerns about youth aging out of care.

At the time, B.C.’s Representative for Children and Youth Bernard Richard said Santanna’s case “raises huge concerns for us.”

“She is part of too many young British Columbians who are being abandoned at age 19.”

Two-year-old Chassidy Whitford died while in Xyolhemeylh’s care in 2002.

A review by the B.C. government in 2003 found the agency did not meet all the requirements of child protection standards regarding the child.

‘Absolutely gut wrenching’

The deaths are “absolutely gut wrenching,” said a former social worker with Xyolhemeylh, who CBC News is not naming because she fears speaking out could jeopardize her current employment.

“I don’t understand how many more children this has to happen to for somebody to wake up,” she said.

Xyolhemeylh was not available for comment.

The ministry said it cannot comment because the government is in caretaker mode due to the recent provincial election and because an investigative process is underway.

“It is important to ensure that work is completed before conclusions or assumptions are made,” a statement said.

There were 98 deaths overall of children and youth who were in care or receiving reviewable services in B.C. from June 1, 2017, to March 31, 2018, according to a 2019 B.C. Representative for Children and Youth report. Thirty-five were Indigenous.

Huge caseloads

Xyolhemeylh assumed responsibility for child and welfare programs for Indigenous youth in the Fraser Valley in 1993.

The agency provides services to 18 First Nations and a number of B.C. urban centres, including Chilliwack, Abbotsford, Langley, Agassiz and Mission. According to the B.C. Government and Service Employees’ Union, of the approximately 4,000 Indigenous children in care in B.C., Xyolhemeylh provides services to over 400.

But a number of reports over the years have shown that delegated agencies such as Xyolhemeylh are struggling.

The former Xyolhemeylh social worker, who also spent a number of years at MCFD, said the beginning of her time with the agency was positive. There was a strong focus on family preservation rather than child protection or removing kids. She said she also appreciated the strong focus on culture.

But about two years in, she noticed a shift. Jobs were getting cut, there were huge caseloads of up to 25 kids per social worker, a high staff turnover, a lack of training and a lack of qualified leadership.

“I had no guidance,” she said.

“You’d start working and get these ridiculous caseloads of high numbers and files that have literally been neglected.”

The union, which ratified a collective agreement with Xyolhemeylh in 2019, agreed that delegated agencies’ workers have heavier caseloads, lower wage rates and fewer benefits than MCFD workers.

A 2017 report released by B.C.’s Representative for Children and Youth showed the B.C. government’s funding to delegated agencies is inequitable and inconsistent and revealed that child protection staff carried an average of 30 cases at a time — 50 per cent more than is recommended.

In B.C., there’s no cap on social worker caseloads.

Audit reveals low compliance rates

The MCFD audit published in January found Xyolhemeylh had high staff turnover and vacancies were left unfilled for long periods of time.

The agency was taken over by the province in 2006 as a result of staffing problems but has been operating under a new delegation agreement since 2010.

The audit found that Xyolhemeylh had only a three per cent compliance rate — instances that conform to a policy, process or procedure — when it came to a social worker’s relationship and contact with a child in care.

It pointed to the large geographical area that the agency covers as presenting a challenge for workers to maintain regularly scheduled face-to-face contact with families and children in care.

When it came to developing a comprehensive care plan, Xyolhemeylh had only an 11 per cent compliance rate, the audit found.

Of the cases the ministry reviewed, 49 per cent did not contain initial and annual care plans.

The audit also found a need for records management training for the administrative staff and consistency in filing procedures between offices.

The ex-Xyolhemeylh social worker said because of the high caseloads, paperwork was often the last thing on social workers’ minds.

Investigations underway

The lawyer for Samantha Chalifoux, Traevon’s mother, is now pushing for a public inquiry into her son’s death.

Xyolhemeylh previously said it had launched an internal review into the death, while B.C.’s Representative for Children and Youth said it is reviewing the case and preparing for an investigation.

CBC News tried to contact contractor Rees Family Services, but its phone numbers listed in the Fraser Valley are out of service. The Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities confirmed Rees is accredited until May 2022.