New Karl Lagerfeld Biography Creates a Stir in Germany – WWD

PARIS — When Alfons Kaiser’s editor at C.H. Beck contacted him last year to ask if he would write a biography of the recently deceased Karl Lagerfeld, the longtime correspondent for Germany’s Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper instinctively turned down the project.

“I said ‘no,’ because it was just two days after his death, and I found it very indiscreet or very unsuitable to even think about a biography,” Kaiser recalls.

Fast-forward 19 months to the release on Thursday of “Karl Lagerfeld, A German in Paris,” Kaiser’s 383-page German-language tome that explores the late designer’s public and private lives. The book has already caused a sensation in Germany since the publication last Sunday of an extract revealing that Lagerfeld’s parents were both members of the Nazi Party.

So how did Kaiser get to this point?

His publisher reasoned that there was no proper German biography of Lagerfeld, though many others have added their contribution to the canon — sometimes with Lagerfeld’s cooperation, as was the case for Marie Ottavi’s book about his late companion Jacques de Bascher, other times despite his fierce opposition (the designer failed to block the publication of Alicia Drake’s book “The Beautiful Fall.”)

“After thinking about it, I said ‘yes,’” said Kaiser, who covered Lagerfeld for two decades since meeting him after a Fendi show in 1999.

“I was queuing up for an interview backstage, when he poured some Coke over his sleeve in the crowd. I handed him a paper handkerchief and asked: ‘Could I ask you some questions, too?’ He replied: ‘I knew that you didn’t give me the tissue just like that.’ He was ever so ironic and clever — you had to love it as a journalist,” he recalls.

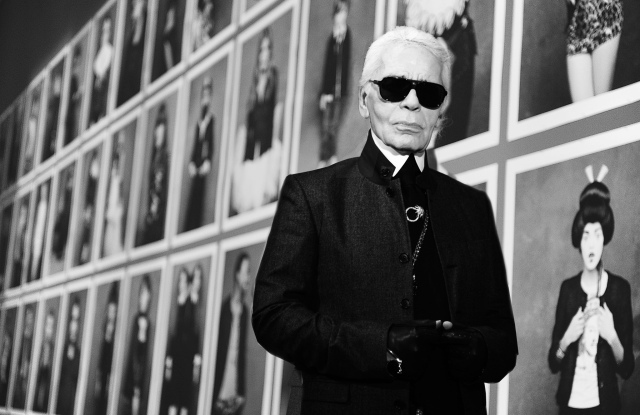

Alfons Kaiser and Karl Lagerfeld at a Chanel show in 2015.

Getty Images/Courtesy of C.H. Beck

Kaiser, who edits Frankfurter Allgemeine’s society and style section, was interested in delving behind Lagerfeld’s carefully constructed public persona, and also in dispelling some popular German myths about fashion.

“They thought he was like a dandy, decadent guy with too much money without doing anything. But as you know, he was extremely hard-working,” he explains.

“And that’s what I want to show, too, that he was working for so many brands, you know, with such an energy, and he was really a very good motivator,” he recalls. “He was a great boss. That’s why many people really worked together with him for a long time.”

During his 13 months of research beginning in March 2019, Kaiser conducted more than 100 interviews with classmates, friends, colleagues, business partners, neighbors and journalists.

“And I talked to some of his relatives, which was not as easy as I thought, because many of them were a bit resentful toward him since he was talking in a slightly arrogant way about people from his past and about some people of his family,” he says.

Among them was Gordian Tork, grandson of Lagerfeld’s aunt Felicitas Bahlmann, and Thoma Schulenburg, the daughter of his half-sister Thea. Along the way, Kaiser uncovered a trove of documents and photographs that shed new light on Lagerfeld’s childhood in Bad Bramstedt, a small town some 25 miles north of Hamburg.

“They moved to the countryside in 1934 when he was just one year old, and of course in the countryside, they stood out because his father was rich,” he explains.

Otto Lagerfeld was a successful businessman who ran Glücksklee, a manufacturer of condensed milk, while his mother Elisabeth was a former sales manager at a department store in Hamburg with a strong sense of style.

“I think my book really shows that Karl got two main sources of his abilities from his mother on the one hand, and his father on the other hand: business and style. Both of them came together in his person, because he was not only a great designer but of course, he was a great businessman,” Kaiser reasons.

The cover of Alfons Kaiser’s biography of Karl Lagerfeld.

Courtesy of C.H. Beck

Among the letters sent by Elisabeth Lagerfeld to her sister Felicitas, which are now in Tork’s possession, was a previously unseen five-page typed document headlined “Why did I become a member of the N.S.D.A.P.?” — the German acronym of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. Though it’s not signed, Kaiser believes she authored it, since she frequently typed her letters.

In the document, Elisabeth Lagerfeld explains how she was initially seduced by Adolf Hitler’s promise of restoring order and economic prosperity after the chaos left by World War I, but that she grew disillusioned with the party when she witnessed Jews being rounded up for deportation in Hamburg in 1941.

“She saw that and thought, ‘That can’t be right.’ And that was the moment when she realized that this was a bad ideology, and that she didn’t like it anymore and she stopped wearing the party insignia,” Kaiser says, although he notes she did not relinquish her party membership for fear of reprisals.

“She was really very open in this letter, telling how she developed and how disappointed she was by the Nazi regime, and how devastated she was by the outcome of the war,” he adds.

After the war, Lagerfeld’s mother declared in an official document that she had never been affiliated with the Nazis. Otto Lagerfeld, on the other hand, explained to the authorities that he had been a member of the party from 1933 to 1945 in the interests of his company, a common practice among businessmen at the time.

Given the well-known historical context, Kaiser was surprised by the response to the revelation. German tabloid Bild on Tuesday ran an article headlined “His Family’s Nazi Secret” alongside a colorized version of a photograph showing Karl, then four years old, looking toward the swastika flag his parents had hoisted to commemorate the annexation of Austria in 1938.

“There are not many people in Germany who are as famous as he was and that’s why of course, they put it like that, but it’s wrong in a way, since it suggests that it’s a scandal, or something like that. It’s not. It was a very normal thing to be a member of the Nazi Party — that’s the truth about German history,” Kaiser reasons.

“It’s no judgment. It’s no direct relationship with Karl himself,” he adds.

Lagerfeld himself often romanticized his childhood, though Kaiser says he doesn’t know if the designer, who was 11 at the end of the war, was aware of his parents’ political leanings. Unlike many other boys in his village, Lagerfeld did not belong to the Hitler Youth movement.

“Most Germans really didn’t talk about all that after the war. That’s why I think that he probably didn’t know what was going on in these years, and moreover he said his parents didn’t talk about politics with him,” he says.

In later life, Lagerfeld frequently spoke out against far-right political parties, namely through the news sketches, dubbed Karlikaturen, that he regularly produced for Frankfurter Allgemeine and its magazine. Did Kaiser not think that the designer would have hated for his family history to become public?

“Yes, I did. But, on the other hand, he was a man who liked to speak out freely and openly, and this is just a historical fact,” Kaiser says. “It is mostly received like that — perhaps not on Twitter, and perhaps not in the commentaries on the web site of Bild newspaper — but it’s mostly seen as a historical fact which would come out one day anyway. So I think he would be at ease with it.”

Pierpaolo Righi, chief executive officer of the Karl Lagerfeld brand, says despite the brouhaha, Kaiser’s book will stand as a definitive account of Lagerfeld’s life. “I really think it’s probably one of the most rounded books, if not the most rounded book, I’ve read about Karl so far,” he says.

“It’s extremely well researched. A lot of work has gone into fact-finding,” adds Righi, who is quoted in the book and read an advance copy.

“The book is a really good reflection of Karl’s life and his persona and his work, and it’s really inspiring to read and gives people a lot of different context, different perspectives. It reveals things that they have not heard, not in a sensational way, but in a way of really to get to know Karl better, and I think that’s a good thing,” he says.

Righi does not believe the revelations will have an impact on the Lagerfeld brand, noting that the designer was no stranger to sparking debate. “He was controversial, and people could agree with him, disagree with him, and that can have a reflection on the brand,” he notes.

But in this case, the events happened when Lagerfeld was too young to have a say. “Who could be angry with little Karl, who happened to be born into this situation?” he argues.

“I can only say that Karl would probably not have liked to allude to this chapter, because he hated the chapter of German history as such in general, and he very much distanced himself from all of that. And I think this is also the life Karl lived, which was very much a life of inclusion, of respecting all people of all origins and races,” Righi concludes.

Chanel, the French fashion house where Lagerfeld was creative director between 1983 and 2019, noted that it did not participate in the book. “The recently unveiled excerpts look back at a period in Karl Lagerfeld’s family history that belonged to him and on which Chanel does not have to comment,” the house, which is owned by the Wertheimer family, said in statement sent to WWD.

A family photograph of Karl Lagerfeld with his nanny, around 1936.

Courtesy of C.H. Beck

Reflecting on Lagerfeld’s sharp mind and even sharper tongue, Kaiser says he believes the designer was shaped by his extremely demanding mother and the experience of being bullied at school in his teens.

“Elisabeth Lagerfeld was a very strict person, very tough, very hard with her son. I write that he developed like he did because he was not only frustrated by his mother being so hard on him, but motivated, too, so that’s one psychological factor which is important in his biography. I think that he overcompensated,” he says.

He dedicates an entire chapter, titled “Demütigung” (“Humiliation” in English) to Lagerfeld’s school years. A loner who preferred sketching to sports, he was ostracized by other boys, who instinctively rejected his sophisticated clothes and aristocratic manners.

“He was a ‘fine’ guy. That means he was not like the others, and that means he was gay. I think there was no word to describe that in those days. You wouldn’t talk about it. He always said that his mother was very liberal with that and she didn’t care,” Kaiser explains.

“But of course, he was confronted with resentfulness, with hate, with being harassed by other boys,” he adds.

“I think that really contributed to his personality since he tried to put on a mask so as not to be bullied anymore. That’s a bit of a paradox, since the mask which he developed during the decades made him famous, and he became even more exposed. But it was like a shield,” he says.

Kaiser still hasn’t lifted the mystery about why Lagerfeld, once he arrived in Paris, started shaving five years off this age — a fact revealed by Drake in her book. He notes that Raphaëlle Bacqué, who published a French biography of Lagerfeld last year, believes it was out of rivalry with the younger Yves Saint Laurent.

He, on the other hand, believes it might be linked to Germany’s Nazi past. “I heard he once said, ‘I was born in a terrible year,’ which was 1933, because the Nazis came to power in that year,” Kaiser says. “You can’t prove it, but it might be one reason for him to tell people that he was born in ’38.”