Moving the Conversation on Black Designers Forward – WWD

The killing of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers reexposed much that had been ignored in the U.S. and in the fashion industry. While much of the world is on pause due to the coronavirus, attention to police brutality, inequality and the mistreatment of citizens in the U.S. and abroad has come to the forefront. Many fashion companies, brands, publications and individuals in the industry have stepped forward to say “Black Lives Matter,” showing support for the movement. Numerous fashion news sites shared stories highlighting Black fashion designers and business owners with the intent to right the ship in its path to progress.

But in doing so, these stories exposed that this moment is history repeating itself.

The demand for equality, fair treatment and more hiring of Black talent in the fashion world dates back more than 50 years. While some aspects of this time are new, thanks to social media and call-out culture, much of this movement has been seen before.

Now, as then, it is Black creatives, models and industry professionals who have led the way, spearheading efforts to make the industry more inclusive and reflective of the public it should be serving. In the past, efforts emerged organically where there were opportunities, but today, new initiatives, grants and organizations are being launched with the intention of creating and maintaining opportunities for the underrepresented.

For instance, Harlem’s Fashion Row, a nonprofit founded in 2007 by industry veteran Brandice Daniel, is meant to support designers of color. According to Daniel, designers of African American and Latino descent account for less than 1 percent of department store offerings’ representation, a number that hasn’t changed in the 13 years since the founding of Harlem’s Fashion Row. The group in June received a donation of $1 million from the CFDA and Vogue’s The Common Thread initiative to support its Icon 360 program that provides help to designers of color during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For Daniel, a former buyer and manager of production at an intimate apparel company, starting Harlem’s Fashion Row was a project “tugging at my heart” as she saw fewer designers of color in the industry. With the organization’s initiatives, emerging designer Fe Noel received an opportunity to sell at Bloomingdale’s in 2019.

But in order to build greater representation throughout the industry, many Black talents feel a key is to change how they are perceived.

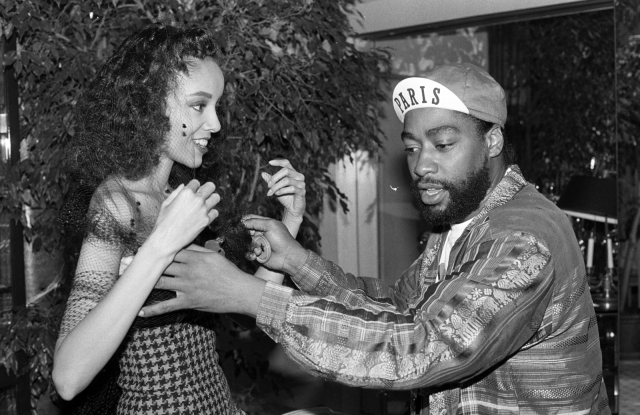

“I think what I’ve been mindful of in all this is how we are seen and how this extends to some people and publications trying to pit us against each other,” said Henrietta Gallina who, alongside Kibwe Chase-Marshall and Jason Campbell, this year started the Kelly Initiative, named after the designer Patrick Kelly. “We are not a monolith, and the challenges we face are complex, so there is no one direct solution. It’s also not the job of Black people to do all of the work. We cannot remove the responsibility of the current leadership and power structures.”

From left: Designer Patrick Kelly’s made-to-order collection at the Martha Inc. boutique in New York. Kelly poses with models in contemporary wedding ensembles from his spring 1986 collection.

Michel Maurou/WWD

“I look at this as a point of continued progress,” said model and activist Bethann Hardison. “Yes, you get to one plateau on the mountain and you can clear it. Then you see another one you have to climb over.”

Sharifa Murdock, Envsn founder and Project and Liberty Fairs cofounder, said, “It’s so unfortunate that we are now being recognized for our talents and our skills, when we’ve always had these talents and skills. Time is just repeating itself, but what’s sad is no one’s speaking on the history. It’s a different generation growing up. Just because we’ve seen it, [it] isn’t how they’re seeing it.”

As companies scramble to show support for the Black Lives Matter movement and do right by Black consumers and talents in the industry, the key question remains: what happened before, and why has it taken so long for the industry — from the boardroom to the design studio — to address the problems?

Gucci and Prada established diversity panels and hired Diversity and Inclusion executives after they received backlash for products bearing racist imagery, but that was only last year. Virgil Abloh’s appointment as artistic director of men’s at Louis Vuitton was a watershed moment, marking the designer as the first Black American to head a collection at one of the largest fashion houses in the world. Yet that came only two years ago.

The CFDA in June took some steps to support Black talents in the industry after the global protests following Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis, but the initiative for mentorship, internships and diversity training programs was not entirely well received because it was seen as hasty efforts that do not go far enough to bring change and progress. In addition to donating $1 million to Harlem’s Fashion Row, they later made donations to the NAACP and Campaign Zero, and through Common Thread donated just over $1 million to 36 companies, including fashion and accessories brands, retailers, factories and organizations. Despite the lukewarm response, the organization is doing something.

June also saw the launches of organizations and initiatives like designer Aurora James’ 15 Percent Pledge; the Black in Fashion Council, led by Lindsay Peoples-Wagner and Sandrine Charles; beResonant, a grant program for Black fashion creatives started by tech company Resonance, and the Kelly Initiative led by Gallina, Chase-Marshall and Campbell who, along with 250 Black professionals, petitioned the CFDA to increase its anti-racism efforts.

The collective effort is unified in seeking to create and maintain sustainable, active and progressive roads for the advancement and equality of Black people in the industry. What is key is to realize that the industry has been here before, starting with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but that progress stalled.

The Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex and religion, while affirmative action programs sought to increase the number of Black professionals in the workforce. After its passage, former Manhattan Borough president Percy Sutton supported programs in New York to educate Black professionals for managerial roles in retail. Several national colleges participated in summer programs to get Black students experience in retail, while the Fashion Institute of Technology developed a “task force” to enroll more Black students.

“Black and Right,” a 1973 article from the WWD archives.

Tonya Blazio-Licorish

At the same time, protests and picketing continued in Washington, D.C., and at the headquarters of various retailers and publications who still engaged in discrimination in their hiring practices. This set the tone for organizations like AIM, The Association for the Integration of Management, and the nonprofit Black Retail Action Group, or BRAG, established in 1970 to increase the participation of Black and minority talent in the retail and fashion industry by promoting career advancement, professional development and networking.

“BRAG’s mission was, and still is, to increase the diverse talent pipeline, something that is more relevant today than ever,” said Nicole Cokley-Dunlap, copresident of BRAG. “The diverse consumer needs to be reflected throughout the decision-making process.” The organization’s other copresident is Shawn Outler, who is also chief diversity officer at Macy’s Inc.

The year that BRAG was established, WWD reported that Black workers accounted for 12 percent of total store employment, 7 percent of white-collar jobs and 2 percent of management, technical or professional positions. Charles R. Perry, a professor at Wharton University who conducted the study, was quoted as saying, “Pure racial discrimination in the form that it was known before the 1960s is not in evidence, inverse discrimination in the form of entry qualifications is predominant.”

Black participation in the fashion industry in the Sixties and Seventies could be credited to Ebony Fashion Fair, said designer Stephen Burrows. Johnson Publishing Co. cofounder Eunice Johnson created Ebony Fashion Fair in 1958 to raise money for Black charities. Johnson not only celebrated her passion for well-known designer fashion from Europe and America on a cabine of Black models like Pat Cleveland and Iman, but she made it a mission to celebrate and expose the world to Black designers. Audrey Smaltz, former model and commentator for the showcase and founder of the Ground Crew in 1977, stated that Ebony Fashion Fair was a game changer for the times. The fair ended in 2009.

Though Johnson urged European designers like Yves Saint Laurent and Valentino to participate in the fair, her insistence on promoting Black American creatives boosted acceptance by the industry for salable, exceptional design contributions from talents like Burrows, Wesley Tann, Jon Haggins, Willi Smith, Scott Barrie, Fabrice Simon, Arthur McGee, and Patrick Kelly, amongst many others.

Support from fashion directors, buyers and retailers brought Black talents into department stores like Bloomingdale’s, I. Magnin, Neiman Marcus and Bergdorf Goodman, which also showcased Black designers in a 1968 fashion show. Burrows’ “Stephen Burrows World,” a partnership with Henri Bendel, set a course for his business in America. A bigger break came for him with the participation in the now-iconic Battle of Versailles in 1973.

Burrows — like Halston, Givenchy, Saint Laurent and the other designers who participated at Versailles — had many opportunities in licensing and collaborations, including designer fur, denim and fragrances. His Stephen B Good fragrance held promise but, according to a WWD article in 1976, it did not garner the same success as his counterparts due to a lack of marketing support.

From left: Model Armina Warsuma in Stephen Burrows’ 1971 collection for “Stephen Burrows World” boutique at Henri Bendel. Model Aria in a dress from John Haggins’ summer 1981 collection.

Tony Palmieri and Harry Morrison/WWD

Haggins, who established his first fashion label in 1966 after graduating from FIT, left the industry in 1973 despite his success and returned to a changed landscape in 1982. “I went in very naïve. I didn’t really see obstacles, because I was enjoying the moment,” he told WWD recently.

He said getting his collection in a department store was not difficult if it was salable. “I made beautiful clothes. That was my business,” he said. “I didn’t look at my race, but if others did, that was not my obstacle, it was theirs.”

Haggins, whose looks sold at major department stores and were worn by celebrities like Diana Ross and Raquel Welch, left the industry again and is now an author, host and producer of Globetrotter TV.

Black models would also see a different level of exposure than their white counterparts. Ophelia DeVore was the first Black model in the U.S. and cofounder of the Grace del Marco Agency. DeVore led a number of protests, including one at Time Inc., according to Jet Magazine, which reported in 1971 that Time asked the New York Supreme Court to drop the “racist journalism” case against them by DeVore’s Charm School.

But as the Seventies wore on — and throughout the Eighties — strides were being taken by retailers and publications to shine a spotlight on Black design talent.

In 1977, Revlon and Bloomingdale’s Marvin Traub, with then-Manhattan Borough president Sutton, hosted “The Black Expression — a Statement of Style,” an in-store fashion showcase and party. In 1979 and 1981, Harvey’s Bristol Crème sponsored a celebrity-attended tribute and fashion show to Black design talent in women’s and men’s fashion at FIT.

From left: Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton attends “The Black Expression — a Statement of Style” event at Bloomingdale’s in New York.<br />Musician Lionel Hampton and fashion coordinator Audrey Smaltz in Fabrice appear onstage during the event.

Michel Maurou and John Bright/WWD

Smaltz, the model who was the fashion coordinator of the event, noted that by 1981 more than 100 black designers were successfully working in the fashion industry.

Hardison, who considers herself more of an “advocate” than an “activist,” founded Bethann Management in 1984 and later the Black Girls Coalition in 1988 to celebrate Black models. Because she was so impressed that “they were all working,” she said, “We now had the opportunity to have Black models on the cover of Elle, a mainstream magazine,” which pushed Condé Nast and Hearst to do the same.

Fairchild’s 1989 event “The Soul of 7th Ave.,” produced by Monique Greenwood, a former editor, and the National Association of Black Journalists, or NABJ, honored models Beverly Johnson, Naomi Campbell, Iman and Karen Alexander, and designers Kevan Hall, Fabrice Simon, Jeffrey Banks, Isaia, Alvin Bell, James McQuay and Kelly, among others. (Kelly was unable to attend and died shortly after due to complications from AIDS. He began his design career in Atlanta, before heading to Paris at the suggestion of model Pat Cleveland. He was the first Black American to be admitted to the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture Parisienne in 1988.)

Despite these successes in America, journalist and best-selling author Teri Agins said Black American designers did not receive the opportunity to lead major European fashion houses. The Nineties saw two appointments of American design talents — with Marc Jacobs signing on at Louis Vuitton and Michael Kors at Celine, both in 1997.

“Tracy Reese and Byron Lars came up at the same time as Jacobs. They were college- and fashion-industry-educated, but they weren’t recruited for those jobs. These are opportunities that they missed out on,” Agins said.

She continued, “There were many talented, developed Black designers at the time who should have been interviewed and considered for such posts. For example, the very talented Edward Wilkerson, who was appointed to be the creative director and designer at Lafayette 148. Edward put that brand on the map!”

Black designers at the time ran the industry spectrum from couture to ready-to-wear and mass-market retail. Among them were Patrick Robinson, who designed at Armani before heading Stateside to lead Anne Klein and later Gap; Hall, who was named creative director to revive Halston in the Nineties and was carried at Bergdorf Goodman, Neiman Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue; Maurice Malone, and Andre Walker.

Others experienced challenges through the lens of success. Gordon Henderson, the first Black designer to win the CFDA’s Perry Ellis Award for Young Designers in 1989 and to secure an exclusive contract with Saks Fifth Avenue, worked with both Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren before launching his own business. He understood as early as his first year at Parsons School of Design that fashion is a tough business.

Designer Gordon Henderson and Melanie Landestoy in his “But Gordon” by Gordon Henderson sportswear collection debut and designer Isaia Rankin with a model in his fall 1982 sportswear collection advance.

Robert Mitra and Dustin Pittman/WWD

“When starting your own business, you are everything — the designer, salesperson and production person,” said Henderson. This is something he says many students are not educated about before entering the business. Education and financial support are both needed and mentorship for new designers through the process is necessary.

Hall said he noticed a shift happening in American design talent around 1995, when New York and Los Angeles-based companies began hiring designers from Central Saint Martins in London.

He said, “Certainly when those positions [to lead major American brands] became available, African Americans didn’t get them. There was a shift in the industry and unfortunately African American designers who helped build the brands to multimillion-dollar status never had the opportunity to launch their own brands.”

Campbell of the Kelly Initiative said, “In the Nineties, amongst my peer group, we were all ascending. As Black representation grew, we realized this is very sectional and very clubby. Our Black peers started to be sidelined, because Black was seen as a trend and an aesthetic of the moment.”

“There was a tendency [for the industry to think] that Black designers only design for Black people,” said Agins. “They see themselves simply as designers who create for everybody.”

Faith Lucas, who designed for Gap and later Tommy Hilfiger, said she fought to be considered simply as a designer. Lucas, who brought success to Gap with her version of the brand’s popular khaki pants, states again, “White designers weren’t called ‘white designers,’ and I felt conflicted about it. Talent does not have that racial demarcation line and we shouldn’t have to think that.”

Henderson agreed with Lucas, as well as Burrows and Haggins, in that each is proud of being a Black designer, but that should not be a buzzword for the industry. “No one says, ‘I am a white designer.’ That’s a given,” said Henderson.

But even as there remained a lack of opportunity for Black designers in many segments of the industry, in the early Nineties, a category of apparel sprouted on the streets of America that created new such opportunities for Black talents: urbanwear.

Spike Lee’s 40 Acres and a Mule garnered much attention for its connection to the director’s Brooklyn roots. Daymond John, cofounder of FUBU, is an early success, securing orders with Macy’s in the early Nineties. Mecca, cofounded by Tony Shellman, Evan Davis and Londo Felix, hit $25 million in sales within 18 months, according to Shellman, allowing for similar success with his second venture, Enyce. “It had a 27 percent operating margin based off of $175 million in sales,” he said. “Before Enyce, Mecca, Karl Kani, there was Major Damage — those brands were already in play, but again, no one knew about them,” said Shellman.

Director Spike Lee poses with a model in his spring 1993 collection and Cross Colours hip-hop sportswear collection advance, fall 1992.

Michel Maurou/WWD

The new music landscape and the call from young Black kids to buy clothes from Black designers gave urban fashion unprecedented power at retail and throughout the industry as even established designers moved to tap into that market. The category provided a starting point for many Black talents with opportunities in fashion, beauty and media.

“Hip-hop was truly a game changer for Black talent in fashion,” said journalist and author Constance C.R. White, who covered the urban apparel boom at its inception.

“There were opportunities at every level,” she said. ”You didn’t come in knowing everything, you didn’t have to. The movement of this category was unlike the ready-to-wear business. As merchants begin to realize they need that Black aesthetic, hip-hop helps to open the door on many levels for Black people in fashion.”

But despite the category’s early success, White said the beginning of the urbanwear boom was treated like a “novelty” and not as a serious cultural moment or significant business proposition.

“You’d be hard put to find coverage of these collections, whether it was the clothing featured or profiles of the designers,” she said. “But as Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel and Isaac Mizrahi show hip-hop-influenced collections they are front-page coverage. In the moment, there was no motivation for it becoming general fashion coverage in the mainstream fashion press and trade organizations.”

Even as urbanwear continued to make strides and more Black designers were featured at retail, the initiatives like those in the Seventies began to fade. “I do believe there is a point where some of us became complacent,” said White. “When we did Fashion Outreach, there weren’t any uprisings, but there was plausibility for unequal treatment. There was kind of this falling away. I think people were quieter about it. People always had this concern of, ‘how might this affect my career.’ People are now more open and louder given what’s going on. It is complacency coupled with a real understandable fear.”

Hardison said she began to see fewer Black models on the runway, which happened after the Black Girls Coalition went dormant in the early Nineties and she closed her representation of models in 1996.

In 1992, she held a press conference calling for greater Black representation in advertising — and 15 years later held a series of town halls focused on the lack of representation for Black models and prejudiced casting directives. She added, “At one point we [at the Black Girls Coalition] had to call out the ad agencies for not reflecting the Black consumer. You’re sort of a watch dog, even if you don’t want to be.”

She said she was told that by the late Nineties, top fashion houses stopped working with glamour models because they distracted from the clothes and model scouts were heading to Eastern Europe for new talent. Casting directors would say “No Blacks, no ethnics” in casting calls. She added, “That’s part of our business. It’s descriptive, it’s like saying no blondes or redheads, but after a while it was beginning to compromise our industry. Then we had to educate them that you couldn’t do that anymore, because it’s inappropriate.”

“When I left, the model representation really fell back. I went right back in and had no problem asking a designer, ‘where’s the representation?’”

This speaks to the fact that the consumer by now is a global one. Hardison never minced words at making the facts known. “I never believed that it couldn’t be flipped.”

From left: MTV’s “Fashionably Loud” event with women’s Enyce urban sportswear for spring 2003. Sean John men’s for fall 2000.

Michel Maurou/WWD

By the Aughts, fashion and its alignment with celebrities gave a new face to the industry. Sean “Diddy” Combs became the first Black designer to win the CFDA Award for Men’s Wear in 2004. From Givenchy to Gap, celebrity prevailed. New cultural and social shifts pushed urban brands to try to reach a broader market. As this category changed, sales growth slowed and the opportunities for Black professionals in the industry further withered in America.

But in Europe, Black talents were appointed at storied design houses. Ozwald Boateng headed to Givenchy as creative director of men’s wear in 2003. He paved the way for designers of color to lead other fashion houses — albeit almost a decade later — like Olivier Rousteing at Balmain in 2011, Haider Ackermann at Berluti in 2016 and Abloh at Louis Vuitton in 2018. Rihanna launched Fenty with LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton in 2019, marking the first time LVMH began a fashion brand from scratch since it set up a couture house for Christian Lacroix in 1987.

Franca Sozzani and Steven Meisel showed support for Black models with the Vogue Black issue, then created Vogueblack.it, a channel under Vogue.it that featured emerging Black models and conversations reflecting the global Black communities.

“But in 2011, the model representation started to fall back a little again,” said Hardison.

On the trade show front, Murdock cofounded Project with Sam Ben-Avraham. After Project was acquired, the two started Liberty Fairs to provide a show platform for emerging and midmarket brands and provide hands-on internship opportunities for young professionals of color. The show launched with 67 brands, of which 10 percent were Black or minority-owned. The show has since grown to 20 percent Black or minority-owned participating brands.

Even as fashion awards and prizes recognize more designers of color, in the end awards and recognition won’t spur the bigger systemic change that has long been demanded and is being called for again with more fervor. While the industry has been put on notice for its explicit misrepresentation of Black culture in design and lack of representation in the talent pool, it finds itself as a familiar place where Black designers recognized for their talent continue to face an uphill battle in terms of financial support and mentorship. And beyond the design studio, there remains a lack of Black representation in the senior executive suite of major fashion and beauty companies worldwide.

Most industry professionals agree that consistent initiatives surrounding education, business management and design collaborations are needed to sustain viability in the industry.

Gallina said, “Seeing that disparity behind the scenes is extra shocking to me. Nothing has changed in the number of Black people I interact with on the corporate level, but the language has changed.”

Chase-Marshall added, “The resistance to transparency from the companies is telling. For me now what is challenging is that the fashion nepotistic and optics rubric has become a casting system and networking game.”

From left: Kevan Hall couture spring 1987 and fall 1988.

Lisa Romerian and Art Streiber/WWD

“One of the things I’ve charged our members to do,” Hall said of the Black Design Collective, a nonprofit he founded with designer Angela Dean, TJ Walker of Cross Colours and Academy Award-winning costume designer Ruth Carter, “as the young people come in the ranks, help get those talents on the movie sets, TV shows and in the studios and really start to lift the young people up. I think it’s important to offer education. We’ve noticed in our workshops that the young people are hungry for knowledge and in knowing the inside-out of the business.”

The collective educates the next generation of design talent entering the industry by providing mentorship and workshops on financing, retail and how to get government funding.

This is the vital support many believe the industry must provide at all levels. As Smaltz said, in regard to the young fashion designer, “You can’t be the creator and the businessperson. You can’t do this by yourself.”

As the industry examines itself from all angles, it is recognizing it needs to change to reflect the currents in society. And while in many cases it has been here before, what executives and brands appear to realize this time is that sustaining these changes is vital to its future.