Melbourne Cup Wager Proves Reserve Bank Point On Housing

Housing

Preparing to tighten controls on investment in a runaway housing market, Governor Adrian Orr offers a timely warning against putting all your money on one horse

Comment: Kiwi runner Ocean Billy could have netted one punter almost a million dollars in last night’s Melbourne Cup. The investor (as we shall call them) wagered $27,500 on the Auckland Cup winner at odds that would have cost the TAB $977,000 if the six-year-old gelding had won.

He didn’t.

Ocean Billy ended up running dead last.

There are two lessons from that. First, don’t rely on Newsroom for racing advice; our story tipped Ocean Billy to win. Secondly, do rely on Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr. Because the morning of the big race, he warned investors against putting all their money on one horse.

Of course, he was really talking to the Property Council about New Zealanders’ predilection for putting all their money into houses, not horses.

New Zealand needs to continue to improve investor knowledge and options to ensure households develop well diversified nest eggs that meet their needs, he said. “Why would you put all your money on one horse – housing – when backing your retirement?”

If that was graphically illustrated by the sight of Ocean Billy trailing home at the back of the Flemington field, it is even better shown by Orr’s charts comparing international asset prices.

Comparing international asset prices

Yes, property investing in New Zealand has out-performed housing in Australia and the US – but it doesn’t come close to the performance of the sharemarket in the US and around the world.

And that’s just over the past three years. Adrian Orr’s real concern, detailed in this week’s Reserve Bank’s biannual Financial Stability Report, is the vulnerability of home owners and real estate investors in the event of another GFC.

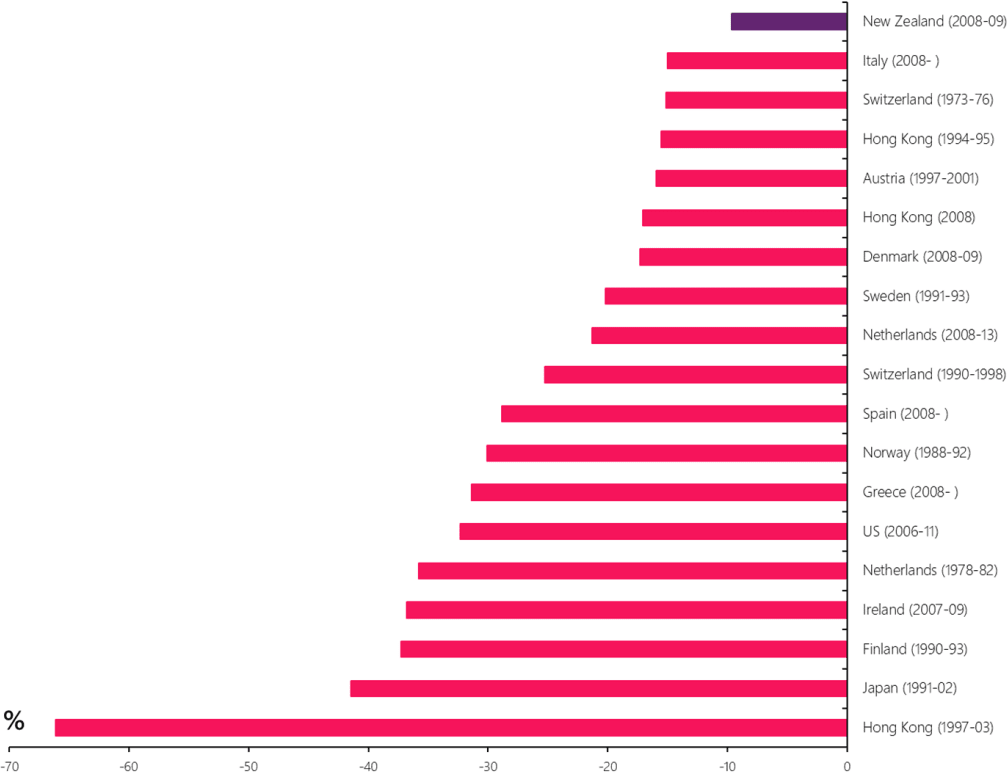

New Zealand got off relatively lightly in 2008/09, but Orr says a number of countries experienced house price declines of more than 30 percent during the Global Financial Crisis. Likewise, OECD studies show that many countries experienced price falls in excess of 25 percent, and house price slumps lasting three to 10 years, between 1970 and 2006.

“You don’t have to go back far in New Zealand’s economic history to get a feel for house price volatility,” he says. “We have experienced periods of sustained house price growth (e.g., the early 1970s and mid-2000s), and declining house prices (e.g., in the late-1970s and early-2000s) in both real and nominal terms.

“The big drivers have been net migration (population growth relative to the supply of houses) and broader economic conditions, especially interest rates and income growth. We are not alone. Asset – including house – price volatility is a global fact.”

Advanced economy house price corrections since 1970

That concern is why the Reserve Bank has reimposed loan-to-value lending restrictions. As of this week, banks are allowed to lend no more than 10 percent of new mortgages to owner-occupiers with a deposit of less than 20 per cent. The constraints on investors are even tighter.

And that concern is also why the Bank is expected today to lay out a path to impose, for the first time, its long-awaited debt-to-income limits. The loan-to-value restrictions mainly protect the banks and other lenders in the event of a downturn – but it is starry-eyed home-buyers who are protected by the debt-to-income restrictions.

“It will come as no surprise to you that in our forthcoming Financial Stability Report we will again elaborate on why we view the level of house prices as unsustainable, and why this matters,” Orr says.

The number of new homes consented per 1,000 residents rose to 9.3 in the year ended September 2021, up from 7.4 in the previous year, Stats NZ revealed this week.

Orr told the Property Council that prices should soon start falling, as a result; instead the pace of price rises unexpectedly quickened.

CoreLogic’s House Price Index, published last night, showed the average national house price rose by 2.1 percent in October, after slowing in the previous five months.

“There is no one agency or silver bullet. House prices and housing affordability are affected by both supply and demand factors, ranging across immigration, tax policy, government benefits or transfers, land availability, building standards, infrastructure, and training programmes.”

– Adrian Orr, Reserve Bank

The higher they climb, the harder they’ll fall – that’s been the Bank’s consistent warning.

“At the source of the financial stability risk is the inability of housing supply to respond in a timely fashion to changes in demand, and the drivers that lead to a bias towards housing as an investment choice beyond simply a place to reside,” the Governor says.

“There is no one agency or silver bullet. House prices and housing affordability are affected by both supply and demand factors, ranging across immigration, tax policy, government benefits or transfers, land availability, building standards, infrastructure, and training programmes.”

Consulting on the new lending restrictions doesn’t mean it will use them anytime soon, nor that it should. But it will give the Bank another option.

Orr is insistent that Reserve Bank adjustments to interest rates and lending rules have played only a small role in the theatre that is rising house prices. Small that role may be, but it is nonetheless a speaking role, and this week he must deliver his lines.

One last note: Newsroom is asking Adrian Orr what wager he placed on the Melbourne Cup. We’re pretty sure he didn’t put all his money on Ocean Billy, though.