Malaysia’s Indigenous people question timber sustainability | Malaysia

Indigenous people from the Malaysian state of Sarawak on the island of Borneo are fighting against plans to cut their forests, saying that while the logging has been certified as “sustainable”, they have not given their consent to the proposals, which could destroy an environment that is home to critically endangered species including gibbons, sun bears and hornbills.

The thousands of Indigenous people who live in the northern Limbang and Baram districts rely on the forest for their physical and cultural wellbeing, while the Baram River is the state’s second-largest and an important life-source.

“Logging will destroy our forests,” Penan leader Komeok Joe said in a statement to Al Jazeera, rejecting the plan. The Penan are a semi-nomadic group living in Borneo.

“It will destroy our rivers and medicines and prevent us from satisfying all of our needs in the forests on which we depend for our lives. We Penan communities reject any logging activities in our Baram territory.”

Village leaders say they were not adequately consulted on a plan by Samling, a Malaysian timber company, to log thousands of hectares of forest. Nor, they say, did they have access to the social and environmental impact assessments conducted for the projects, even though Samling was certified under the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS), which operated by the Malaysian Timber Certification Council (MTCC) and is endorsed by the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), a leading international forest certification body.

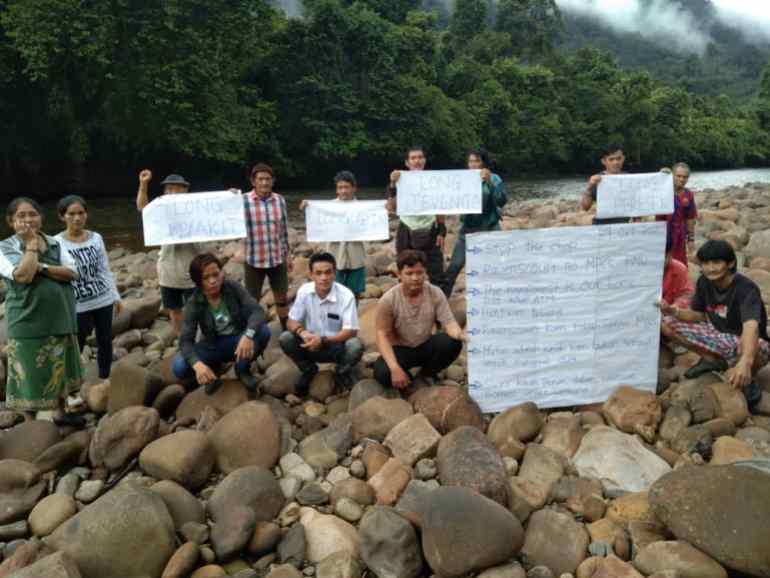

Several communities dependent on forests in Baram and Limbang districts are against logging in these areas [Fiona McAlpine/The Borneo Project]

Several communities dependent on forests in Baram and Limbang districts are against logging in these areas [Fiona McAlpine/The Borneo Project]The communities worry that that certification will allow wood from the trees to be sold as “sustainable” in international markets.

Certification without consent

Samling received the certification for its 148,305-hectare (366,469-acre) Gerenai concession in April this year in the Upper Baram – an area double the size of Singapore.

In the Kenyah Jamok village of Long Tungan, community members say they were not consulted nor made aware of the MTCS certificate until it was granted to Samling.

Instead of logging, they say they want to preserve the environment and are working on a community conservation and ecotourism initiative.

“None of us in Long Tungan were ever visited by anyone from MTCC. How can they say that we have given our free, prior and informed consent?” asked Jamok community leader John Jau Sigau.

Danny Lawai Kajan from the neighbouring village of Long Semiyang also rejects logging in his area.

“Enough is enough. We want the trees to grow back,” he told Al Jazeera.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the concession in the Kenyah village of Long Julan, Patrick Keheng says his community is also opposed to the plan.

“Samling failed to consult all stakeholders in a transparent fashion,” Keheng said. “We do not want any more destruction to our forest, no more logging.”

The Kenyah Jamok community of Long Tungan say they have not been consulted on matters affecting their land rights [Fiona McAlpine / The Borneo Project]

The Kenyah Jamok community of Long Tungan say they have not been consulted on matters affecting their land rights [Fiona McAlpine / The Borneo Project]It is not the first time Samling has been accused of neglecting the rights of Indigenous peoples and causing environmental damage.

Samling was founded in 1963 by Sarawak businessman Yaw Teck Seng, who currently heads the Miri-based conglomerate with his son Yaw Chee Ming.

Samling’s business, involving logging, plantation, construction and property development spans the globe from Southeast Asia, to China, Russia and the United States. The father-son duo was estimated to be worth $480m by Forbes Malaysia in 2020.

In 2010, the Norwegian Pension Fund divested millions of shares in Samling after its Council on Ethics concluded that the company had contributed to illegal logging and severe environmental damage in Sarawak and Guyana.

The environmental watchdog, Global Witness, has condemned Samling for its “egregious track record of illegal logging, primary rainforest destruction and violation of indigenous rights” in countries including Malaysia, Cambodia and Papua New Guinea.

Elsewhere in Sarawak, in Upper Limbang, Samling received certification for its 117,941 hectare (292,438 acre) Ravenscourt concession in 2018, but Penan communities in the area say they only learned of its existence in July of this year when the MTCS certificate was due to be re-evaluated.

The area in question is home to some of the last unspoiled tracts of forest in Sarawak, and is part of an important Borneo wildlife corridor. The concession borders the Pulong Tau National Park and Mulu National Park, a World Heritage site renowned for its gigantic limestone caves.

A logging truck belonging to the company Samling transports tropical wood from the Sarawak rainforest [Fiona McAlpine / The Borneo Project]

A logging truck belonging to the company Samling transports tropical wood from the Sarawak rainforest [Fiona McAlpine / The Borneo Project]“As long as the company cuts down the forest in our area, we do not agree,” said Ketua Baru from Long Adang, one of the villages.

“These communities have repeatedly expressed that they do not want logging on their land,” said Penan leader Komeok Joe.

Samling did not respond to Al Jazeera’s request for comment. Instead, the company pointed to several press statements released in rebuttal to earlier allegations.

It says: “The Group operates in a lawful manner and is dismayed by the allegations made. We observe strict guidelines for all our activities, including the certification process, which is naturally part and parcel of our operational plan towards ensuring responsible management of forest resources.”

Stop the Chop!

Affected communities have now joined hands with Indigenous rights activists and environmental campaigners to launch a campaign called “Stop the Chop!” in an attempt to put an end to what it alleges is “the certification of conflict timber in Sarawak.”

Campaigners are urging the PEFC to use its influence to ensure that the MTCS meets its standards.

The PEFC is a global alliance of national forest certification systems, based in Switzerland, which says it is dedicated to promoting sustainable forest management through independent third-party certification.

Penan communities in Upper Limbang say they reject all logging by Samling and certification under the MTCS [Keruan/Supplied]

Penan communities in Upper Limbang say they reject all logging by Samling and certification under the MTCS [Keruan/Supplied]Last month, Samling invited communities affected by the Gerenai concession to a seminar to learn about the certification process.

Representatives from the MTCC and the Forest Department Sarawak also attended, but Peter Kallang, chairman of the indigenous organisation SAVE Rivers says Samling’s seminar “was just a facade to fulfill their corporate obligations. SAVE Rivers urges Samling to take heed of the matters raised at the seminar and take responsibility.”

Community members who attended the seminar said they were frustrated and compared the event to a “meet and listen” session.

“What I can conclude about the seminar is that it’s non-interactive. We never got to ask any questions after each speaker finished their presentation. We had to wait till the end to do so,” says Lusat Tebengang from Long Palai.

MTCC’s Chief Executive Officer Yong Teng Koon told Al Jazeera the MTCC met SAVE Rivers following the seminar to “listen to their concerns and provide additional clarification on the due processes provided by certification.

“We take any complaints against the MTCS very seriously and work tirelessly to ensure they are investigated to ensure the highest standards of sustainable forest management are maintained by all forest managers who have voluntarily agreed to abide by these standards and have submitted their management to be assessed and certified against them.”

The MTCS uses third parties to audit the certification for forest management. The process involves independent certification bodies which have to evaluate the application of forest managers to forest management certification standards.

Campaigners say ‘Stop the Chop’ in the Sarawak rainforest [Peter Kallang/SAVE Rivers]

Campaigners say ‘Stop the Chop’ in the Sarawak rainforest [Peter Kallang/SAVE Rivers]Beyond Sarawak, environmental campaigners from the United States and Switzerland told Al Jazeera that the issues raised by Indigenous communities should concern the PEFC and the international community.

“It’s the PEFC’s role to prevent this conflict timber from entering the international market labelled as sustainable,” said Annina Aeberli from the Basel-based Bruno Manser Fund.

“If the PEFC does not take action knowing the flaws in the issuance of certificates, then they would be helping to greenwash tropical timber and questioning the reliability of their own standards.”

“The international community should be very concerned about bogus timber certificates being issued in Sarawak,” said Fiona McAlpine from The Borneo Project, which brings international attention and support to community -led efforts to defend forests, sustainable livelihoods and human rights. “Our efforts to stem the tide of the extinction and climate crises will all be for naught if we can’t trust labels that claim to uphold sustainability.

“Indigenous communities in Sarawak are on the front lines of the climate crisis and they need our support.”

PEFC CEO Ben Gunneberg says the organisation will be meeting concerned stakeholders including SAVE Rivers and the Bruno Manser Fund to learn more about their issues in Sarawak and how best to address their concerns.

Indigenous peoples in Sarawak are battling to save some of the state’s last intact forests [Annina Aeberli / Bruno Manser Fund

Indigenous peoples in Sarawak are battling to save some of the state’s last intact forests [Annina Aeberli / Bruno Manser Fund“We are aware that, as with any certification programme or activity, issues of non-conformity or non-compliance may arise, and need to be thoroughly and independently investigated,” he said, stressing that PEFC has a complaints and appeals mechanism to deal with alleged breaches of the code.

“A thorough investigation of all complaints is in our best interest, as just one non-compliance by a certified entity poses a potential risk to the credibility of the entire system,” he said.