Kings, designers, freedom fighters: students of color reimagine their future | Milwaukee

Amir Williams pictured himself as an African king, supported by his family’s ancestors. Miguel Rivera imagined holding a Rubik’s cube, layered with infinite possibilities. DeMarcus Staples saw himself as a hero, confident and steady while saving lives.

The students, all 16, recently completed a year-long art program that helps students in Milwaukee explore their identity through video, photography and oral histories. The project, which is run by New York based non-profit Art Start, culminates with the youths staging a portrait that represents how they see themselves.

The program counters the popular narratives young men of color in Milwaukee receive from the state around them, one that produces the highest incarceration rate for Black men in the nation.

More than half of all Black men in Milwaukee have spent time in prison before they turn 40, one study found in 2013. In the public school system, Black, male students are treated more harshly and punished more often than their white classmates.

Reggie Jackson, a Milwaukee historian, traces the disparity to a hyper-segregated school system, an overwhelmingly white teaching force, and punitive, zero-tolerance policies that emerged nationwide following the 1999 Columbine school shooting.

“It creates a perfect storm of inequality within the schools,” Jackson said. “The incarceration machine starts early, and it swallows opportunity in Milwaukee.”

Since 2017, more than 40 Milwaukee public school students have taken part in the program, imagining themselves as fashion designers, freedom fighters, music producers and superheroes. “This project allows them the opportunity to be children, to be human, and for people to see them as such,” said Johanna De Los Santos, Art Start’s executive director.

“There’s all these crises converging during the pandemic – and racial tension and hostility in the midst of it,” said David Castillo, a planning assistant with the school district’s office of Black and Latino male achievement, which has partnered with Art Start. “Our boys are still navigating that somehow, while saying that the pandemic isn’t going to be an excuse for why they don’t get up and grind everyday. There’s power in that.”

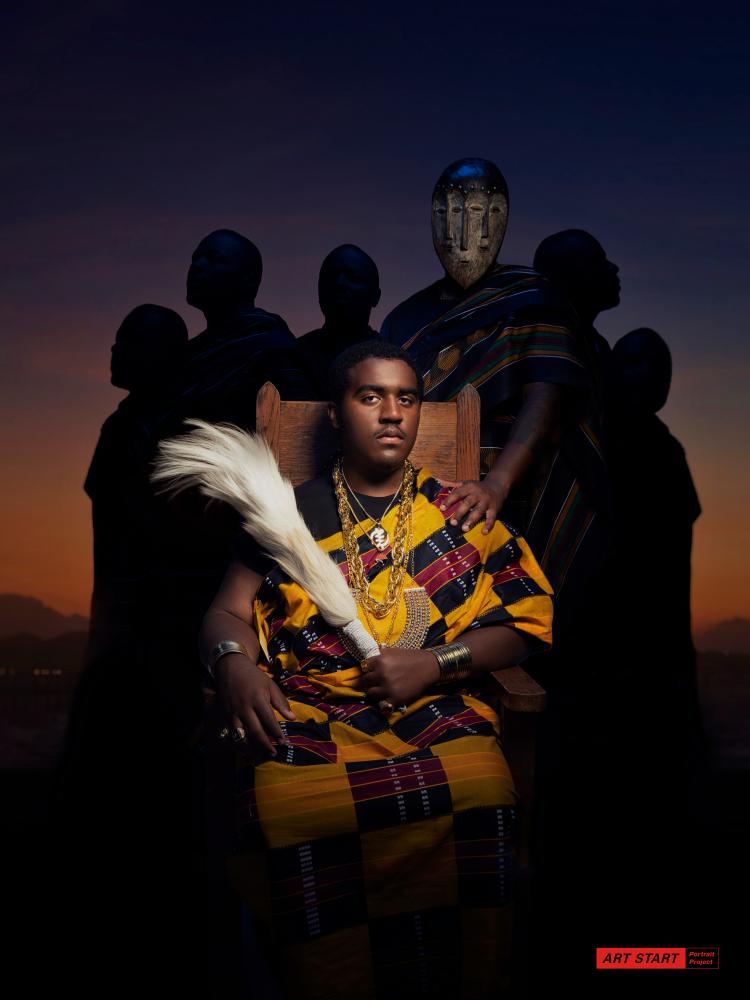

Amir Williams

A desire to discover his roots attracted Amir Williams to the image of a king as he created his portrait. In the artwork, Williams is joined by a masked figure – a nod to those who came before him.

“My ancestors wake me up every day, telling me to keep striving for greatness and keep learning about my past and history so I can teach others,” he said of his portrait. “A king is fair. A king is always able to listen to people. The smartest man in the world is able to give information, but always trying to take it in,” he added.

Milwaukee schools have been virtual since Covid shut their doors in March. Williams misses going to school in person. “Screen time gives me a headache,” he said. “I’m not a person who can just sit there. I need an in-person perspective.”

With his downtime, Williams has been boxing; he hopes to become a prizefighter. He reads books on African history, reflecting on the connections between past and present. His perspective on the dynamics that shaped his city are both historically informed and deeply personal – formed by the pawn shops and liquor stores owned by people from outside his neighborhood and the family members he’s lost to the forces of mass incarceration, gun violence and the war on drugs.

“People think we’re just in the hood selling dope, but it’s deeper than that,” he said. “It goes back to white supremacy and the removal of opportunities. It’s like we’re trapped under a lid that’s screwed on tight.”

What resources would help other young men of color? “Apprenticeships,” he said. “We need access to jobs. When the factory jobs left Milwaukee, that’s when the Black community fell. I can’t name 10 Black people who own their own house.

“Create economic opportunity for students of color. Because right now, it doesn’t look tangible to us,” Williams said.

Miguel Rivera

The Rubik’s cube is a window in the way Miguel Rivera sees the world. And it’s a place of endless opportunity.

“I want people to see me with my cube in my hand,” he said. “The cube has an infinite world of algorithms.”

Soft-spoken and deliberate, Rivera is aware of the stereotypes around Latino youth, but refuses to give them his time. He doesn’t like to focus on the negatives.

“No one disagrees with me when I have the cube,” Rivera said. “People just tell me, ‘Oh, that’s good. That’s a good way to go.’”

Rivera plans to be an engineer – ideally for a company that makes Rubik’s cubes.

During most of a 45-minute Zoom interview with the Guardian, Rivera spoke with his camera off. But when questions turned to the cube, the camera instantly flicked on for an unprompted demonstration of skills. Colored blocks spinning furiously, Rivera spoke of memorized strings of algorithms that help him solve the puzzle in under 20 seconds.

“It’s all very simple,” Rivera said. When he doesn’t have a cube, he plays in his head. He wants to hold the world record.

The oldest of six children, Rivera finds time to complete online school work when he’s not caring for younger siblings or helping his father with construction jobs. “It’d be easier to focus on work in a classroom where there’s no distractions,” he said.

His family has been very cautious about the virus and he doesn’t host many friends at his house. He draws strength from his grandma, who teaches him to cook and has instilled a sense of right and wrong. If he could change anything in the world, he says he’d end the pandemic.

DeMarcus Staples

“Heroes are reliable. They can be counted on. You can be a hero on the battlefield or a hero to a child who needs a mentor,” said DeMarcus Staples. “You don’t necessarily have to be a hero to be a man – but you need to be willing to be one if someone needs you to.”

Exploring the idea of heroism interested Staples in the image of a combat medic – a possible career stop on his path to become a surgeon.

The past year of online learning hasn’t changed Staples’ career plans, but it’s been a slog at times. “I truly hate online school,” he said. “As a hands-on learner, it’s truly horrible. This is the worst my GPA has ever looked.”

Crushing news came when the football season was canceled. He had worked hard to become the team’s starting quarterback, he said, hoping to land a college scholarship to help him pay for school.

He’s preparing for next season, hitting the gym when he’s not in class. Some nights he works DoorDash to make some money. But you won’t find him on the streets of 53206 – Staples’ home zip code that’s known for staggeringly high incarceration rates. He spends nearly all of his time outside the area.

Staples doesn’t waste time worrying about whether his appearance or neighborhood gives others a preconceived notion of who he is.

“We can’t control what people see when they look at us. I can’t convince you that I’m not a criminal just because I’m Black. But I can show you I’m not by what I do. If you choose not to believe that after I show you, that’s on you,” he said. “If you consistently do the right thing, someone will notice.”

Staples has leadership qualities, and he knows it. That confidence breaks through in a video that accompanies the portrait project and captures the moment he takes in his portrait for the first time.

“I’m the only one with the headset,” he said of the image on the battlefield.

“Wanna know why? Because I run it. I run this.”