India sought probe into ex-RBI gov Rajan for helping ‘white man’ | Business and Economy News

New Delhi, India – A year after the government led by Narendra Modi’s BJP came to power in 2014, the top finance ministry official accused the Reserve Bank of India of setting interest rates to benefit developed countries and sought a probe into its conduct, a trove of official documents obtained by The Reporters’ Collective reveals.

Finance secretary Rajiv Mehrishi, working under the then-finance minister, the late Arun Jaitley, made the claim after the RBI opted to prioritise controlling rising prices over lowering interest rates, which would have made borrowing cheaper for businesses and citizens.

Although the government and the RBI having different views is not unusual, the revelations mark the first time a top government official has accused the RBI of working to benefit “the white man” in “developed countries” and sought an investigation into the “real purpose” behind the central bank’s decisions.

The documents, which were accessed by The Reporters’ Collective (TRC) under the Right to Information Act, are being made public for the first time as part of a three-part investigative series.

At the time in 2015, the RBI governor was Raghuram Rajan, an appointee of the previous, Congress-led government. The BJP government chose Urjit Patel as Rajan’s successor.

But the RBI didn’t cut the interest as sharply as the government wanted, even under Patel. So the finance ministry called a meeting with the bank’s newly set up monetary policy committee (MPC) to push it to cut interest rates, according to the documents. The unprecedented meeting fell through when committee members declined to attend, a development widely reported in 2017.

The attempt to influence the central bank came despite the Modi government having amended the Reserve Bank of India Act in 2016 to strengthen the firewall between the RBI’s primary function of controlling prices and the government’s political impulse to spur growth even at the cost of rising inflation.

The RBI’s then-governor Patel pushed back, wrote to the government saying it should stop trying to influence the RBI in order to preserve the “integrity and credibility” of the new monetary framework “in the public eye and our parliament”. Otherwise, the government would be in violation of the letter and spirit of the law that protected the RBI’s independence.

As disagreements piled up on this and other issues, Patel resigned on December 10, 2018, citing “personal reasons”. The government replaced him with Shaktikanta Das who, as a top finance ministry bureaucrat, had justified increasing the government’s influence in the RBI’s rate-setting function, official documents reveal.

Different roles

One of the RBI’s key roles is to control the amount of money and credit available in the economy through the interest rate at which it lends to banks – this is the central bank’s monetary policy function. Lower interest rates spur economic growth in the short term but can also lead to an increase in the prices of goods and services, or inflation. Untamed inflation erodes the value of money in the hands of citizens, particularly the poor, acting like a hidden tax that hits poorer and lower-income citizens more than the rich.

Monetary policy is typically kept independent of government control because politicians face the temptation to create more money and spend beyond their means on populist schemes and vanity projects. In the long run, excess spending by the government harms the economy.

Differing analyses of where inflation may be headed and how interest rates should be set often create tension between central banks and governments in many parts of the world, including India. But in New Delhi, the debate took an ugly turn when the Modi government came to power in May 2014 as India was witnessing one of the highest levels of inflation in the world.

Newly appointed finance minister Arun Jaitley announced that the government would establish a monetary policy regime that would focus on keeping inflation in check with transparency and accountability. This would be a departure from the existing system where the RBI governor alone set interest rates, without an inflation target at hand.

In February 2015, as a first step towards establishing an MPC, Mehrishi and then-RBI Governor Rajan signed an agreement outlining an inflation target for the first time. The central bank committed to bringing inflation down to 6 percent by January 2016 and 4 percent in subsequent years, with a goal of maintaining it within a range of 2 to 6 percent. If the RBI failed to meet the target, it would be required to send an explanation letter to the government.

‘Subsidised’ the rich abroad

In 2014, Rajan kept the repo rate – the rate at which the RBI lends to banks – unchanged at 8 percent due to inflationary concerns. As inflationary pressures eased in 2015, he started cutting the rate, bringing it down to 7.25 percent by June. But in the August 2015 meeting, he maintained the status quo.

The Modi government was not satisfied with the cuts, with Jaitley and chief economic adviser Arvind Subramanian often publicly criticising the RBI and complaining that borrowing costs were still too high.

Their public venting, however, was only a hint of the pressure being applied behind the scenes, documents show.

On August 6, 2015, two days after the RBI announced its latest rate decision, finance secretary Mehrishi wrote an internal note, asking for the interest rate to be cut sharply to 5.75 percent.

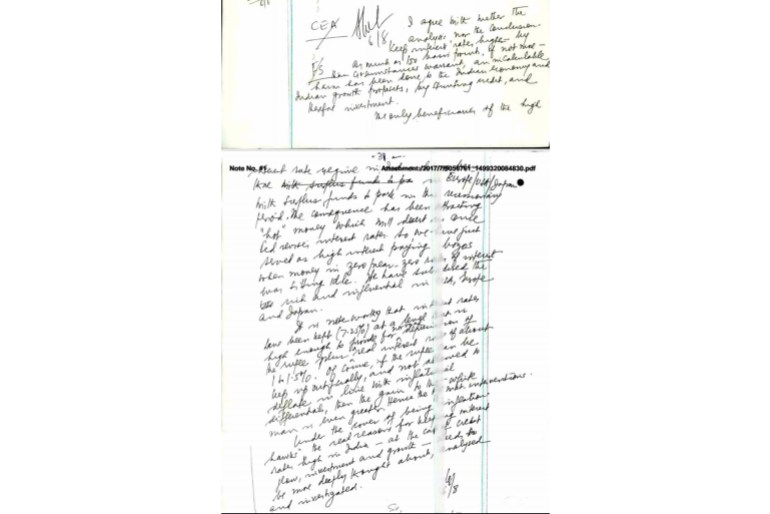

“I agree with neither the analysis nor the conclusion [of the Reserve Bank of India’s monetary policy committee] to keep interest rates higher by as much as 150 basis points [or 1.5 percentage points], if not more,” Mehrishi said in his note. “An incalculable damage has been done to the Indian economy and Indian growth prospects, by stunting credit, and therefore investment,” he added.

Mehrishi then accused the RBI of helping wealthy foreign businesses at the cost of Indian businesses and citizens, claiming the “only beneficiaries” of India’s high interest rates were developed countries.

“We have subsidised the rich and influential in the USA, Europe and Japan.”

In developed countries, interest rates are typically lower than in India, encouraging some investors to temporarily park their funds in the Indian financial system to mint profits from the higher interest.

“Under the cover of being ‘inflation hawks’, the real reason for keeping interest rates high in India – at the cost of credit flow, investment and growth – needs to be more deeply thought about, analysed and investigated,” Mehrishi said in his concluding remarks.

Finance minister Jaitley acknowledged Mehrishi’s note on the file and “desired a discussion”.

The MPC finally came into place in September 2016, days after Rajan moved back to the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business to teach finance. He was replaced by Deputy Governor Urjit Patel who was also involved in the making of the new monetary framework.

A month later, when Patel chaired the first MPC, it cut the interest rate by 0.25 percentage points. In its November board meeting, the central bank led by Patel approved Modi’s decision to invalidate overnight most of the existing currency, the so-called demonetisation, in which 500 and 1,000 Indian rupee notes ceased to exist as legal tender.

Some economists accused Patel of letting Modi railroad the RBI into approving one of the biggest domestic economic disasters and denting the central bank’s autonomy. Rajan would later claim that the government had consulted the RBI during his tenure on demonetisation but never asked it for the nod.

Almost as if responding to the criticism of diluting its autonomy, the MPC adopted a tough stance in its next meeting in February 2017 when it changed the “monetary policy stance” from accommodative to neutral. That change in “stance”, which surprised analysts, was a signal to the financial markets that the MPC would no longer be open to rate cuts.

The central bank kept the rates unchanged in the subsequent meeting of the MPC in April 2017, while the government scrambled to resuscitate an economy hit by demonetisation.

Rising tensions

With Patel resisting government pressure, the finance ministry attempted to influence the RBI’s independent Monetary Policy Committee which sets the interest rates.

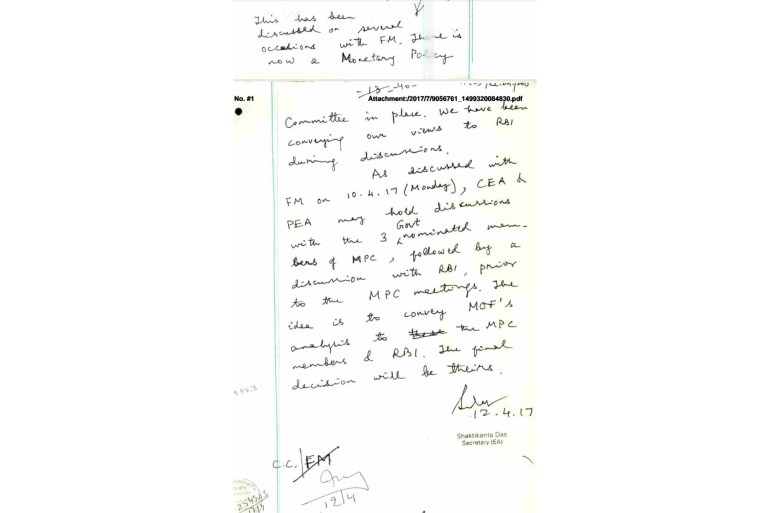

On April 10, 2017, Jaitley held a meeting with his economic affairs secretary Shaktikanta Das during which they decided that then-chief economic adviser Arvind Subramanian and then-principal economic advisor Sanjeev Sanyal would hold a meeting with the “three government-nominated members of MPC, followed by a discussion with RBI, prior to the MPC meetings,” documents show.

In a note on April 12, Das wrote, “The idea is to convey MOF’s [ministry of finance] analysis to the MPC members and RBI. The final decision will be theirs [RBI].”

The MPC comprises three members from within the RBI, including the governor, and three external experts appointed by the government. MPC decisions, which are supposed to be made independent of government influence, are based on a majority vote. In a tie, the governor has a casting vote.

Under the Modi government’s law establishing the MPC, the government is only allowed to present its views to the committee in writing. Government officials cannot meet with the committee or influence it by any other means.

Ignoring the law, on May 17, 2017, the finance ministry sent a letter to each of the MPC members stating that “with the approval of the Finance Minister, it has been decided to evolve an institutionalised framework under which the government may, from time to time, engage with the members of MPC to provide the government perspective on macroeconomic situation including economic growth and inflation”.

The MPC’s external members were summoned for a meeting chaired by Subramanian on June 1, 2017, days before the committee was scheduled to meet. A separate letter was written to Urjit Patel telling him about the finance ministry’s decision to hold a discussion with the RBI officials on the MPC at its headquarters in Mumbai.

Three days later, the finance ministry reversed course and said in a file note that the discussions would only be informal because of the “sensitivities involved”.

“A revised letter may be sent to the MPC…without mentioning that we would like to institute a mechanism for informal discussion with them,” the note said.

A new letter was issued to all the MPC members, which specified that the meeting to be chaired by the government’s chief economic adviser is only to “discuss the overall macroeconomic situation in the country and developments in the global economy.” Any direct reference to interest rates, the real purpose of the meeting, had now been left out.

The letter

On May 22, 2017, Patel wrote back to Jaitley opposing the meeting. He said the RBI was “surprised and dismayed by this development on two counts”, according to the documents reviewed by The Reporters’ Collective.

“Firstly, we have not discussed the matter with each other, although we have interacted several times in recent weeks on work matters; and second, it is addressed to and seeks to set up meetings with MPC members, and separately so with non-RBI and RBI members,” Patel said.

He stressed that the move “violates the letter and spirit of the amended RBI Act (to set up an independent committee for monetary policy) and tarnishes the constructive engagement since 2014 between RBI and the Ministry of Finance on issues relating to monetary policy”.

“In fact, communication with or from (the) government should be scrupulously avoided if the integrity and credibility of the monetary policy decision has to be preserved in the public eye and our Parliament,” Patel wrote, adding that investors will “likely” take a dim view of any direct intervention in monetary policy.

“Frankly, this is avoidable as we seek, in the national interest, to nurture institutions befitting a modern economy,” the ex-RBI governor said.

Patel reminded Jaitley of the clause that the federal government can convey its views only in writing to the MPC from time to time and said that any other structure for communication will violate the law.

“This clause (where the operating words are “writing to the MPC”) was, you may recollect, precisely formulated so that, in a departure from the past, informal and non-transparent “direction” by government officials on monetary policy is disallowed,” his letter said.

Al Jazeera sent a list of questions to the Ministry of Finance, the RBI, Rajiv Mehrishi, Raghuram Rajan and Urjit Patel. None of them responded.

Das’s parting words

In the finance ministry’s final internal note on the matter, Das, the then-economic affairs secretary, wrote that an “interaction between (the) finance ministry and members of MPC cannot be interpreted as coming in the way of the RBI Act.”

“Ultimately, accountability about (the) functioning of the economy lies at the doorsteps of the government, particularly the finance ministry,” Das said in a note dated May 29, 2017, while giving the approval to send the finance ministry’s analysis of the economy to the MPC members in writing.

Das, toeing the government line, would become RBI governor one and a half years after his departure in May 2017 from the finance ministry. He was appointed barely 24 hours after Patel abruptly resigned in December 2018.

Part 2 of the investigative series will be out tomorrow.

Somesh Jha is a member of The Reporters’ Collective.