I Trained My Ears, Hands To Detect Car Faults – Blind Mechanic Tells His Story

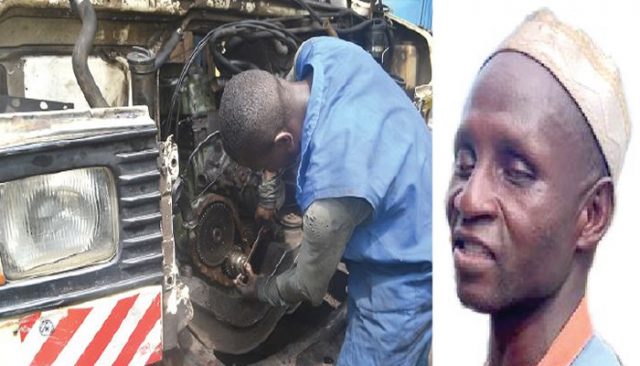

The story has been told of Murtala Shuaibu, the Nigerian man who is blind and yet works at his job as a mechanic.

Without a doubt, there are perhaps a few people in the world today who can hold on to their goals and convictions tenaciously through the haze of disabilities like Murtala Shuaibu.

The visually impaired mechanic, who hails from Agbede, in the Estako West Local Government Area of Edo State, has been fixing cars for over 30 years.

Among many residents of Tugamaji, a community on the Gwagwalada Expressway, Abuja, where Shuaibu’s auto workshop is located, he is popularly known as ‘The blind mechanic.’

However, his popularity soared on social media recently when a Tik Tok user, who claimed to be one of his clients, made a short video about him.

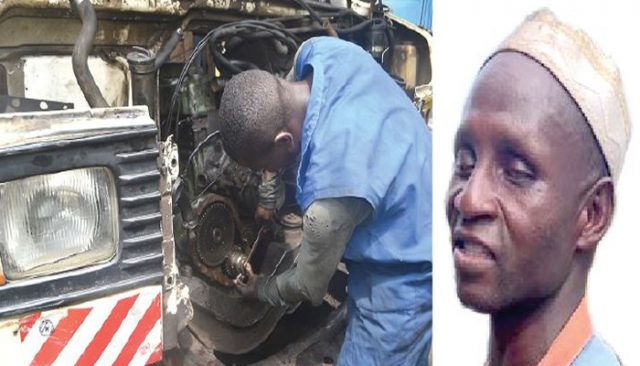

In the viral video, which has now been viewed more than 80,000 times, the 55-year-old blind mechanic briefly describes how he accurately troubleshoots and fixes a variety of automobiles.

Speaking with Saturday PUNCH, the father of two, who resides in Kano State, said he became blind while driving a car in 1996.

With a tinge of confidence in his voice, Shuaibu explained that the encouragement he received from people around him boosted his resolve to continue working as a mechanic.

He said, “I am a visually impaired mechanic. I am 55 years old and I have two children – a boy and a girl. I started learning this work in 1988 but I went blind in 1996.

“Before then, I was physically ill and sought treatments, some of which I think had side effects that affected my sight. I started to have blurred vision in both eyes. Initially, I thought it would go away but it got worse.

“One day, while I was driving, I lost my sight and could no longer see with both eyes. It was like being in the dark all of a sudden, but I resolved to continue as a mechanic because that was the only source of living that I knew.

“At the initial stage, I was living in regret but people around me encouraged me not to dwell on my disability but continue with my work and there were people who believed in me.

“That was what convinced me to continue working. I became visually impaired before I got married, so I decided it shouldn’t stop me from my life goals.”

Trained ears, hands

Having lost his sense of sight – which is vital for his job – Shuaibu began to steadily adjust to the proficient use of his sense of hearing and touch to repair cars.

He recalled, “At first, it was very challenging to repair cars as a visually challenged person. I thought it was impossible for me to fix cars, identify their defective parts and gauge their problems without my sight. In fact, I almost gave up in discouragement, but my persistence and courage kept me going.

“I had no other means of work and rather than become a beggar, I decided to put my mind into adjusting to my new situation. So, I began to train my hands, nose, and ears to make up for my lost sight. I mastered car parts with my hands and attuned my ears to the sound of engines so I could detect when there’s a problem. That is why if I hold a spanner in my hands, I can tell its size and use my hands to chart where I should apply it.

“I also rely on my nose to sense if there is a fault with the cars I work on. After a period of years, my ears became sensitive to figuring out what is wrong with a car and my hands adapted to changing automobile parts with minimal assistance.

“Now, once I listen to the noise of your car, I can tell you its problem whether it is coming from the amber or there is a stabiliser leakage or the nozzle needs to be serviced and fixed. I work on Toyota, Honda, and other some other cars.”

From his early beginning as an apprentice to a local mechanic, Shuaibu steadily began to gain mastery of the skills required to fix automobiles.

Soon, he began to receive positive feedback from his clients who marvelled at how he easily figured out car faults and from there, they began to recommend him to their friends and colleagues.

Describing how he works on a regular day to our correspondent, Shuaibu noted that it took regular practice and patience to hone his sensory abilities.

“When you bring your vehicle to me, I will ask you to start the engine and then I listen carefully to it. When you rev the engine of a car, and something is wrong with it, if you listen carefully, you will hear some abnormal sounds that will emerge from it. Mechanics know this.

“There are times I ask the person patronising me to open up the bonnet and I will use my hands to decipher or check what I think may be wrong. I can show you what is wrong or mention what you need to buy. If you want to buy the part yourself, that’s fine. I can send someone to help me buy it and fix it for you.

“But to be sincere, sometimes, it is unbelievable how I work on cars and I can easily detect what the owners don’t detect.”

Challenges encountered

In spite of his determination to transcend the limits of his visual impairment, Shuaibu still has to contend with certain challenges.

He said, “There are some people who find it difficult to trust me with their cars because I am blind. They wonder how it is possible for me to figure out what is wrong with their vehicles when I lack the physical sight that they have.

“When I first started, it took much time and effort to convince my clients of my capabilities. Some also try to underpay me or argue with me when I tell them their vehicle’s requirements. Fortunately, I can recognise my clients by their voices and I am well-known within my workshop community.

“Some curious people come around just to watch me as I work. Others bring me their cars and as I do the repairs, they are amazed and recommend me to their friends and colleagues at work.”

As a visually impaired mechanic, Shuaibu still has to rely on the support of people in order to navigate the city and travel to be with his family in Kano, a city which is 423 kilometres away from his workshop.

“I have the support of my friends and family members that help me. Though I work here in Abuja, I live in Kano with my wife and children. Sometimes, I have to close the workshop before 7pm when it gets dark in order to get home safely. It can be dangerous out there for people like me and you can’t tell who is who.

“When I want to travel to be with my family, I usually go in the company of my friend. Although there are several occasions that warrant me to rely on the kindness of others to cross gutters, board buses, or ensure my safety in public.

“I have a friend, Muhammed Ibrahim, here in Abuja under whom I work. He owns this workshop. My stay in Abuja is temporary, maybe for three or four months before I return to Kano State.

“Ibrahim sometimes goes to work on clients’ cars where I wouldn’t be able to go physically because of my condition. I stay with my friend whenever I am here in Abuja, and I also have a younger brother who also lives in this city.”

He added that accommodation and transportation, particularly for the visually impaired are two of the most potent difficulties he had to contend with.

“Accommodation is one of the biggest challenges I contend with here. Another is mobility, especially for someone that is blind. Some of my clients live far and their cars have broken down completely in need of my intervention, and they have come to trust me.

“There is a physical limitation that my condition places on my profession and that is why I hope to get a means of transportation with which I can be going to meet my clients when their cars develop problems rather than waiting for them. I am also planning to get my own shop so that I can work freely in a space that is suitable for my physical challenge.”

In his final remarks, the blind mechanic urged youths, particularly those with physical disabilities, to always focus on their abilities and not allow themselves to be discouraged.

He said, “Youths should have job skills even with education. People with disabilities are also gifted in their own unique ways and they must not allow themselves to be discouraged.

“Young people should always recognise their potential and encourage themselves. If I was surrounded by people who discouraged me when I became blind, I would have quit this profession.”

***

Source: The PUNCH