How to Win the Pandemic’s Activewear Boom | Intelligence, BoF Professional

LONDON, United Kingdom — Sweatpants, yoga leggings and sports crop tops are the hero products of the pandemic.

Though not immune to the retail downturn, activewear is selling out more frequently than before the pandemic hit and it has avoided the heavy discounts seen elsewhere in the market, said Kayla Marci, an analyst at retail market intelligence firm Edited. In the US, sales are down just two to three percent year-on-year, compared to a decline in the mid-double digits for other apparel categories, according to Earnest Research, which tracks US credit and debit card purchases. Online sales of activewear jumped 30 percent in August compared to a year earlier.

It’s “really completely outperforming almost every other apparel sector,” said Michael Maloof, associate director at Earnest Research. “Overall, it’s the brightest spot in apparel and accessories.”

But it’s also a crowded market that’s difficult to master. Form-fitting leggings and trendy sweatshirts are easy to copy, and competition is fierce at every price point. Similarly, few companies have the resources to compete with the likes of Nike and Adidas, which spend hundreds of millions of dollars each year on technical innovation. For startups that raise venture capital, there’s the added pressure of answering to investors who expect rapid growth.

“It’s not so easy to build a sustainable business,” said Matt Powell, vice president and senior sports industry advisor for The NPD Group.

On the other hand, the pandemic surge is opening new opportunities for well-placed independent brands. Rising star Gymshark saw US sales skyrocket, climbing by an average of 163 percent year-on-year in July and August, according to Earnest Research data. For the week of July 1, sales spiked 856 percent year-on-year. LA-based Alo Yoga was ranked the fastest-growing activewear brand in the US by web traffic, which grew 132 percent year-on-year between March and July, according to analytics firm SimilarWeb.

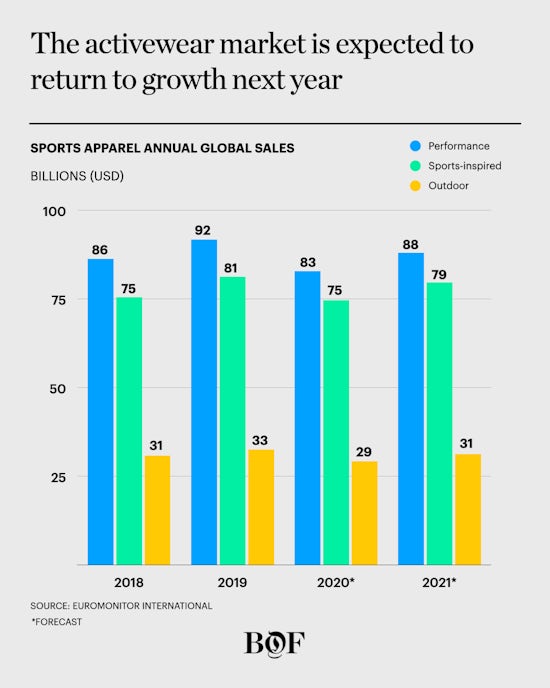

Sales of activewear are expected to grow 6.5 percent next year, according to Euromonitor.

“Coming out of Covid we are going to see a more intensified interest in health and wellness [with] people putting an emphasis on healthy living and staying fit,” said NPD’s Powell. “Obviously, that bodes well for activewear.”

Brands that can capitalise on this moment will be well set up to thrive after the pandemic, but it won’t be an easy game to win.

Digital Head Start

When lockdown forced Alo Yoga to shut its seven stores and yoga studios, it felt like a major blow. But in reality, cancelled wholesale orders and lost retail sales only counted for a small proportion of revenue. About 90 percent the business is digital, split between e-commerce sales and an “Alo Moves” subscription business, where subscribers can take yoga and fitness classes on-demand.

This year, Alo’s direct e-commerce sales have more than tripled compared with last year, while class subscriptions have jumped roughly six or seven-fold, said co-CEO and co-founder Danny Harris.

“Every yoga studio essentially shut down,” he said. “Our digital platform was a big beneficiary of people needing a place to still practice.”

The company is one of a generation of digitally-focused brands that were well-placed to capitalise on consumers’ homebound shopping habits before the pandemic.

Players with more physical store exposure have been harder hit, and those with less established digital platforms will likely continue to struggle. Currently online sales of activewear in the US are about 10 percent higher than they were going into the crisis, said Earnest Research’s Maloof, despite brick-and-mortar stores reopening their doors.

It’s a shift that’s set to continue. Prior to Covid-induced lockdowns, about 20 percent of activewear sales were online, according to NPD. Powell estimates this will rise to 30 percent over the pandemic, and hit 40 percent within the next few years. That puts pressure for companies with a traditional physical retail footprint to rapidly up their online game.

“Companies that are online natives and dominate those channels are going to be better poised,” said Maloof. “The direct-to-consumer brands are in that position right now.”

Community Matters

Even with a strong online platform, it’s easy to get lost in the growing sea of lycra. The brands gaining traction in today’s market have a keen understanding of their customer and how to talk to them.

Take Gymshark, the white-hot social media phenomenon, beloved by a generation of fitness buffs and avid gym-goers. Shoppers were lured by a combo of affordable pricing (a pair of leggings retails for £45, while a gym tee costs £15) and the brand’s fanbase of fitness influencers like Denice Moberg and Lex Griffin.

Its Instagram is full of reposted content of gym training exercises and bodybuilder physiques (think muscular biceps and overt six packs) and from its social media influencer circle. Year to date, Gymshark has generated $200 billion in earned media value, a metric that quantifies the dollar-value of digital content — roughly triple that of Lululemon — according to marketing technology firm Tribe Dynamics.

Turnover hit £176.2 million in last year, up from £40.5 million in 2017, company filings show. In August, the company raised its first round of equity funding, valuing the business at $1 billion.

“Having a strong marketing campaign and something that resonates with people is key,” said Edited’s Marci. “Gymshark is talking about relevant issues and political topics, they’re really staying focused with what’s going on outside of the activewear space and really connecting with that consumer.”

Sportswear’s giants are muscling in on the action too, spotting new revenue streams in providing online classes and content. Lululemon built its brand on a physical version of the community-marketing model and has bold ambitions to up its engagement online. Nike has leveraged its digital apps like the Nike Training Club, which offers a range of tailored workouts, to continue to connect with consumers during lockdowns, while Adidas leaned on its Runtastic app.

Pace Yourself

Upstart brands looking to capitalise on the activewear boom have an uphill battle to compete with these more established players, those who benefit from better liquidity, scale and pre-existing brand recognition. But they also need to manage new growth smartly to avoid burning out.

Take the cautionary tale of Yogasmoga, the brand founded by former Wall Street bankers Rishi and Tapasya Bali in 2013 with ambitions to become the next Lululemon. Within two years, it closed a series B round, valuing the company at $74 million. It laid out an aggressive expansion strategy: “[By 2018] we expect to have 125 stores and a corresponding valuation of $1 billion,” Bali told BoF in April 2016. Yet, by December 2016, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. It was overextended and at odds with its main investor.

When raising vast sums of venture capital, companies also take on expectations of rapid growth and a swift return for investors. Brands facing an intensely uncertain financial future may prefer to proceed with caution.

For instance, cult running brand Tracksmith took a conservative approach to growth to avoid some of the mistakes other fast-scaling, direct-to-consumer companies have made, said Matt Taylor, CEO of the five-year-old brand he co-founded in 2014. To date, the brand has raised $6.7 million funding.

“We have a more conservative — and hopefully sustainable — vision, in terms of how we want to grow the brand over time,” he said, noting he sought out investors “that also understand the reality of starting a brand from scratch, and how much time that takes to build a really strong and wide foundation before you can start to really accelerate growth.”

“We’ve seen a handful of successes come out of this model of, you know, raising tonnes of capital and going as quickly as possible. We’ve also seen a lot of failures and probably we’ll see a lot more,” he added.

For Alo Yoga’s Harris, it was a similar story. The company has never taken on any private equity funding, despite many approaches. Harris firmly denied any plans to sell the company, but did not rule out the possibility of a public listing later down the line.

“We’ve just grown the business in a sustainable way, what we believe is the right way,” said Harris. “We continue to reinvest the money that the business has made over the years. It takes a lot of discipline to do that, but it’s allowed us to… stay on our path.”

Related Articles:

How Lululemon Built Athleisure’s Leading Brand

Sweatsuits and Yoga Pants Are Selling Like Crazy. What Happens When Lockdowns End?