How to Survive the Future of Retail | Opinion, Retail Prophet

Films about the future very often present the world that awaits us as a dark dystopia dominated by a handful of malevolent mega-corporations, controlling much of consumer life on Earth. Robocop’s Omni Consumer Products, Alien’s Weyland-Yutani or Blade Runner’s Tyrell Corporation are only a few examples of such futuristic corporate nation states operating with impunity in a world in which they’ve become pervasive. In a post-pandemic retail landscape, such corporations will no longer reside solely in novels or films. They will become a reality.

When we do finally emerge from the coronavirus pandemic, the world of retail will be a very different place. The scattered bones of small to medium-sized businesses, troubled legacy brands, ailing distribution formats and cash-strapped retailers and shopping mall owners will be strewn across the landscape.

Covid-19 is the commercial equivalent of a meteor impact: an existential, once-in-a-century event that will change the chemical composition of the industry’s atmosphere. The result will be a complete eradication of many retail species, frantic adaptation by others and the rapid growth and evolution of a few. A new class of predator will emerge: an entirely novel, genetically mutated species of retailer that faces few threats. In nature, they’re referred to as apex predators. In retail, they’re called Amazon, Alibaba, Walmart and JD.com.

The Rise of ‘Apex Predator’ Retailers

As a group, their annual revenues amount to approximately $1 trillion. Their collective active customer counts reach into the billions. They know no geographic, temporal or categorical boundaries. Minor fluctuations in their share prices on any given day can equal or exceed the entire market value of corporations like the Ford Motor Company.

Covid-19 is the commercial equivalent of a meteor impact.

While fatal for so many retailers, Covid-19 has been and will continue to be an intravenous drip of metabolic steroids for these apex predators. As a species they will all emerge from this crisis bigger, stronger and with more power than ever before. While many retailers swooned under revenue declines of up to 80 percent, these giants posted results deserving of a double take.

Evolution, though, is a double-edged sword. As with any predator that rises to the top of the food chain, their increasing size proves both an advantage and a hindrance to their continued dominance. Their outsized metabolisms require ever larger, more nutrient-rich prey.

This is not to suggest that there aren’t some obvious sources of enhanced revenue and profits currently in front of them. Penetration into new growth markets such as India, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa provide rich new hunting grounds. There is also increased focus on membership and subscription programs, locking customers into ongoing auto-replenishment systems for routine and regular household purchases. Enhanced share of fashion and especially of the luxury markets holds potential, particularly for Amazon, which has until now been seen as a pariah by luxury brands. Media and music platforms, as well as advertising revenue, all provide significant opportunities for continued growth and expansion. Moreover, increased deployment of robotics, as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos put it, “vaccinate” their supply chains to future crises and drive even more human costs and labour issues out of their back-end operations.

But not even these categories and technologies will offer enough nutritional value to sustain the kind of jaw-dropping gains investors will have come to expect from these behemoths by the time Covid-19 becomes a memory — which could be years from now. So, in order to fuel their continued growth, these apex predators will need to find entirely new food sources with higher caloric content — much higher than can be achieved by merely peddling more running shoes, electronics and household items.

This news should be cause for worry among all businesses, but it should be particularly concerning for incumbents in sectors that have been ruled largely by gated oligopolies such as the banking, insurance, healthcare, education and transportation sectors. Not only have these sectors been traditionally reticent to self-disrupt, Covid-19 has shone a bright light on their respective vulnerabilities. And that has the apex predators circling their prey.

In nature, they’re referred to as apex predators. In retail, they’re called Amazon, Alibaba, Walmart and JD.com.

Banking, Transport, Healthcare, Education…. What’s Next?

Six years ago, Alibaba’s Ant Financial didn’t exist. Today it is valued at more than Goldman Sachs with a $150 billion valuation, meaning that if it was stripped out of Alibaba, it would stand as one of the 15 largest banks in the world. Ant also offers credit cards, credit scoring, loans and wealth management. And if that weren’t impressive enough, the Ant Financial fund Yu’e Bao is now the world’s largest money market fund at over $250 billion.

Alibaba is hardly the only apex predator venturing into the banking and payments sector. By 2019 Amazon had built, bought or borrowed at least 16 different fintech products and platforms, stitching them together to fuel growth of their ecosystem. It has also been active in providing loans to its merchant partners and providing payment terms to customers, all in an effort to serve its own ends: more merchants and more customers with more money to spend with more merchants. And Amazon might just decide to offer some sort of quasi-checking product to Amazon Prime members, who make up roughly half the American adult population – something experts in the sector have already cited as entirely possible.

Then there’s the insurance sector. Through Amazon Protect, the company is already offering insurance on consumer goods ranging from electronics to appliances. There’s no reason to believe that as Amazon further expands the realm of its offerings into homes, luxury items, automobiles and other major purchases that it will not also seek the insurance revenue that comes with them. And it’s not alone.

In 2018, JD.com received approval for a 30 percent investment in Allianz China, making it Allianz’s second largest shareholder. Only a year earlier, JD.com’s investor partner Tencent made a similar entry into the market, buying a majority stake in Weimin Insurance Agency and receiving approval to sell insurance products over Tencent’s digital network.

These apex predators are also coming for shipping and delivery. FedEx Chairman Frederick Smith said during an interview in March 2017, “Well, let’s make sure we understand the definitions; Amazon is a retailer, we’re a transportation company. So, what that means is, we have a tremendous amount of upstream hubs, sortation facilitates, flights, trucking routes and so forth. Amazon is about you coming to their store.” He went on to say, “Amazon doesn’t deliver many of their own packages at all.” Suffice to say, his comments didn’t age well.

In the years that followed, almost as if to vex Smith personally, Amazon expanded its logistics footprint, enlarged its fleet of owned trucks, leased cargo jets and grew its Amazon Flex delivery program, sort of an Uber for parcel delivery. Little more than two years later, as it became apparent that Amazon was no longer a customer but a competitor, FedEx announced that it was ending its ground delivery deal with Amazon. What few realised at the time was that Amazon was already delivering 50 percent of its own parcels to consumers. FedEx was dead. They just didn’t realise it yet.

This year, Amazon tipped its hand a little further, acquiring self-driving transport company Zoox for $1.2 billion, and revealing plans for an autonomous taxi company. There can be little doubt that such a venture would also include the advent of autonomous delivery vehicles that would dramatically reduce Amazon’s last-mile expense. As with most things Amazon, I expect they will perfect the science and technology of shipping to a point that, like Amazon Web Services, it’s offered as a service to other companies, yielding yet another multi-billion-dollar revenue stream.

Healthcare is also on the agenda. Covid-19 thrust many of us forward into the world of digital healthcare with new velocity. As The New York Times writer Benjamin Mueller put it, “In a matter of days, a revolution in telemedicine has arrived at the doorsteps of primary care doctors in Europe and the United States. The virtual visits, at first a matter of safety, are now a centerpiece of family doctors’ plans to treat the everyday illnesses and undetected problems that they warn could end up costing additional lives if people do not receive prompt care.”

The global healthcare market is estimated to be approximately $10 trillion and will grow at a CAGR of 8.9 percent to nearly $11,908.9 billion by 2022, according to a recent market report. In the United States alone, healthcare spending amounts to close to $4 trillion. Meanwhile, the global ePharmacy market was valued at $49.7 billion in 2018 and is projected to reach $177.8 billion by 2026. And both Amazon and Walmart have been salivating over the opportunity.

In one of its most decisive moves in the space, Amazon partnered with JPMorgan and Berkshire Hathaway to provide a new healthcare programme for their combined 1.2 million employees. The venture, dubbed Haven, takes direct aim at many of the long-recognised deficiencies in the American health system, such as soaring costs, onerous administration processes and a bias toward treating illness, rather than promoting health.

If that weren’t enough, Amazon’s $1 billion acquisition of PillPack gave it pharmacy licenses in all of the 50 US states. The company’s massive and ongoing investment in grocery provides a natural tie-in with health and wellness and its physical locations — like Whole Foods — provide on-the-ground destinations for future medical clinics in high-income markets.

Walmart is assisting with the kill. In June of 2020, Walmart announced that it was acquiring technology as well as intellectual property from CareZone, a start-up that focuses on helping people manage multiple medications. The company’s multi-pronged approach on both pharmacies and healthcare clinics makes it, in Morgan Stanley’s estimation, “a sleeping giant to watch,” in the healthcare sector.

Alibaba also wants a piece of health insurance. The company currently offers healthcare through Ant Financial, which, almost immediately upon its introduction, attracted 65 million users with the goal of eventually netting 300 million users — or just shy of the population of America — on one healthcare plan. This would make it larger than any other insurance entity.

Education is also in their sights. Covid-19 has forced hundreds of millions of students worldwide onto online learning platforms, many of which were cobbled together quickly and imperfectly by colleges and universities. Many incumbent institutions and educators themselves had resisted the pull of online education, citing academic concerns, but it would be naive to believe the reluctance isn’t also tied to fears of lost tuition fees.

The Chinese education market is estimated to be worth 453.8 billion yuan or $65 billion in 2020, according to a report from iiMedia. Tencent, China’s primary social platform and 18 percent owner of JD.com, is stepping up to take a share with what it calls “Smart Education,” a complete educational platform for K-12, vocational schools and ongoing education students that the company hails as “a more fair, personalised and intelligent education.” With over 1 billion active users, the penetration of programs like Smart Education could be staggering.

Similarly, Alibaba has its own stake in the education market. It currently offers Banagbangda meaning “Help me answer,” a homework helper app. In addition Alibaba’s Youku, who recently launched a video platform, has launched a study at home platform. This, in combination with the company’s DingTalk online collaboration tool, positions it to be a player in China’s exploding education market.

Break Them Up?

In the pre-pandemic world antitrust investigations abound. But the pandemic has made these apex predators a truly indispensable lifeline for their customers, their merchants and, ultimately, to their respective national economies. Given that political fire is usually a product of voter sentiment, it’s reasonable to assume that these companies will be treated with kid gloves, at least in the short-term. They will have become just too indispensable. Besides, governments, many of them in chaos, have bigger fish to fry.

The result of this unique window of opportunity will allow for an almost inextricable penetration of these companies into the lives of global consumers. Much the same way we forget how much we depend on electricity until there’s a power outage, these apex retailers will become the essential utilities that power our consumer lives. This will not only catapult their growth to new heights, but also allow these mega-marketplaces to establish a secure foothold in these new and exponentially more profitable categories. It’s that penetration into highly profitable categories that will put these brands in a position to use their product marketplaces less as a source for revenue and profit and more as an instrument purely aimed at acquiring more customers — bread crumbs that bring a steady stream of shoppers, who once converted can then live much of their lives inside the ecosystems these brands offer.

These apex retailers will become the essential utilities that power our consumer lives.

It becomes quite easy to imagine a future state where you receive one monthly charge for everything from the food in your refrigerator and the shoes on your feet to your home insurance and the cost of your kid’s tutoring and all provided by one company. And this will spell disaster, not just for many retailers but for any business that sells anything to human beings on earth. Having embedded themselves in so many aspects of consumer life, they will form a barbed-wire fence of value around their customers that becomes almost impenetrable. The result will be an almost total domination of the middle-ground in every market and category.

SURVIVING PREDATOR GIANTS

So, where does that leave everyone else? How will businesses survive in the lengthening shadows of these giants? While it may seem a death sentence for competing retailers, it need not be. That said, for those residing amongst these apex predators, a radical rethinking of their competitive positioning and the value they offer the market will have to happen.

A good place to begin is by acknowledging that beyond the human and economic toll exacted by Covid-19, the pandemic has also acted as a temporal wormhole pushing almost all of society from the industrial to the digital age. Work, education, entertainment, communication and even social experiences themselves have had to rapidly evolve and adapt to a physically distanced world. Sure, it’s a change that was steadily underway pre-pandemic, but the virus ripped the bandage off. We have crossed the digital divide and burned the bridge that got us here.

Media Is the Store, The Store Is Media

If it wasn’t already becoming obvious, Covid-19 finally slapped the retail industry into seeing that physical stores are not only an impractical and expensive means of distributing products, but that they’re incredibly vulnerable to disruption. Increasingly frequent interruptions brought on by social unrest, climate change and, of course, pandemics all spell potential trouble for physical stores in the future. In a world where our iPhones are open for business 24/7, the inherently limited availability and access offered by brick-and-mortar stores renders them increasingly inconvenient.

But to be clear, this in no way negates the value of physical stores as community gathering places, brand culture hubs and experiential playgrounds. It is however time to stop considering them an effective means of product distribution. Stores must become more about distributing experiences and less about distributing goods. Because the two are rapidly trading roles.

In the minds of today’s consumers, “the store” actually starts with media experiences. TikTok is the store. Instagram is the store. YouTube, my television and gaming console or a virtual fashion show on my mobile — these are all fast becoming the store. The apex predators have already accepted this reality by building commerce, finance, entertainment and streamlined logistics into every media experience hosted on their platforms. Indeed, for these giants, media has not only become the store, it’s a more efficient, contextual and effective transaction point. In 2016, Jack Ma called this “the new retail.” In four short years, it’s become table stakes.

Meanwhile, smart brands have also awakened to the idea that physical stores can be an incredibly effective means of acquiring new customers and promoting online sales, especially given the skyrocketing cost of digital advertising. Physical stores can also be a tremendously cost-efficient hub for last mile delivery, regardless of how the shopper chooses to buy.

If you can’t serve your customers through every media touchpoint, you’re going to go out of business.

The moral of the story is that if you can’t serve your customers through every media touchpoint, you’re going to go out of business. If your brick and mortar stores are not creating vastly positive and memorable physical media experiences and brand impressions you’re going to go out of business. And if you can’t effectively weave these two, media and store, together in a way that removes buying friction and adds radical experiential value for customers, you’re going to go out of business.

Positioning in a Post-Pandemic World

Most crucially, with the centre of the market across categories commandeered by the apex predators, all retail brands will have to rethink and reestablish their market positioning.

Historically, we’ve viewed market positioning as a value spectrum ranging from commodity to luxury, with most brands seeing themselves somewhere in the middle. But if any single phenomenon has defined the last 50 years in developed economies it has been the evaporation of the middle market, forcing brands to push to the extremes of value.

More recently, we’ve added in the dimensions of customer convenience versus customer experience as a means of further defining brand positioning. The assumption has been that a customer experience-focused brand could somehow get away with not being so convenient and vice versa. But in a post-pandemic world, convenience and customer experience will no longer be mutually exclusive or optional for brands — it doesn’t matter if you’re Gap or Gucci, your products will have to be shoppable, purchasable and shippable every minute of every day.

Moreover, in a world where the default option for almost all product needs is a handful of mega marketplaces, all other brands will have to establish vastly more distinct value propositions.

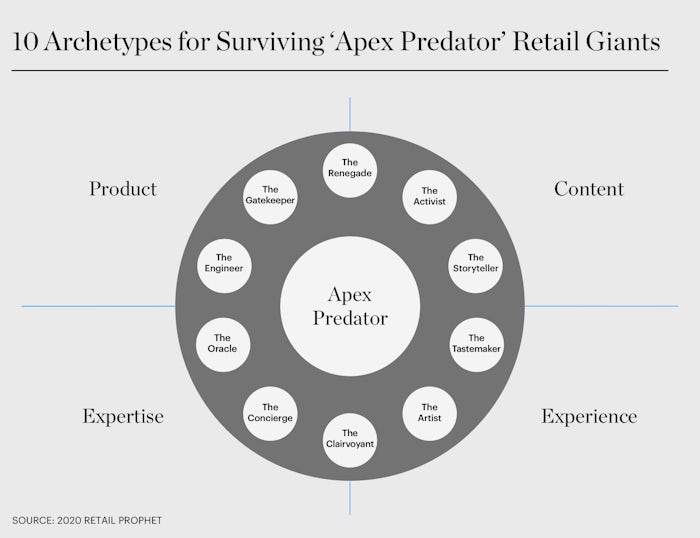

The 10 Retail Archetypes

Retailers who intend to survive in a post-pandemic world will have to secure a position based on what I see as ten distinct retail archetypes. Each represents a valuable and ownable market position, provided a brand dedicates all organisational energy and resources to operationalising it. While the concept of brand archetypes is not new, these retail archetypes are aimed at being less esoteric and offering a greater sense of how to operationalise a chosen position. Which one are you? Or better yet, which one should you become?

1. The Renegade: Renegade retailers challenge incumbents in a market by identifying creative product or operations-related unlocks that radically alter the price-value equation. They leverage technology, people, supply chain efficiency and systems thinking to redefine customer experience in their chosen categories. The Renegade dedicates all its energy, resources and assets to its battle against the status quo. It highlights the inherent shortcomings of the current customer experience in their category and underscores its unique method as the way of the future. These brands differentiate themselves on the basis of product and/or experience and reinforce their anti-status quo approach at every touchpoint.

- Points of differentiation: Uniquely easier or better buying system

- Examples: Warby Parker, Casper, Costco

2. The Activist: Activist retailers use their businesses to support social, economic or environmental causes. They not only champion their cause; they bake it directly into their products and their business model. They align every communication and experiential touchpoint back to the North Star of their cause. Customers and employees select activist retailers based on their own sense of moral alignment with the cause.

- Points of differentiation: Societal good and ability to affect change

- Examples: Body Shop, Patagonia, Bombas

3. The Storyteller: Storyteller retailers are those that grow so large, ubiquitous and iconic they supersede their own product category. They come to represent a higher societal ideal or aspiration. These retailers, often vertically integrated brands, spend the majority of their effort creating compelling content, editorial, events and experiences both on and offline, resulting in a deep sense of community affiliation. In essence they are branded media companies that sell quality products. Storyteller retailers see their stores not as mere distribution channels for product, but as stages that can be used for media production, live-streaming and community events.

- Points of differentiation: Content and community

- Examples: LVMH, Nike, Apple

4. The Artist: Artist retailers very often sell products that are similar or even identical to those of other retailers, but through their sheer creativity and capacity for stagecraft they design experiences around those products that are highly unique, engaging and differentiated, thus winning them distinct positioning. These are retailers that differentiate based on customer experience both on and offline. They measure their stores not only from the standpoint of traditional retail metrics but also for the media value of each positive consumer impression.

- Points of differentiation: Customer experience, retail theatre and engagement

- Examples: Showfields, Camp, Selfridges

5. The Tastemaker: Tastemaker retailers are those whose products or brands are not necessarily unique but may indeed be more difficult to find. Tastemaker assortments are carefully sourced, curated and merchandised with a clear nod to the more discerning shopper in a particular category or those aspiring to a particular lifestyle. And beyond products, some tastemakers will even curate unique brands and businesses in one central location, saving shoppers the time and effort of researching on their own.

- Points of differentiation: Deep knowledge of trends and ability to expertly curate products and experiences

- Examples: Neighborhood Goods, Gadget Flow, Williams Sonoma

6. The Oracle: The oracle retailer is one who delivers unparalleled expertise within a specific category. These retailers go beyond simply offering product knowledge by hiring and nurturing passionate category enthusiasts to engage customers and speak from personal experience about the use of their products. The emphasis on service and knowledge makes them appealing to both professional and consumer users.

- Points of differentiation: Unparalleled product expertise and customer support

- Examples: B&H Photo, Recreational Equipment Inc.

7. The Concierge: Concierge retailers are those that deliver highly personalised and engaging experiences to their shoppers. These retailers thrive by taking service to the level of an art form, both online and off. They place emphasis on customer delight and afford employees significant autonomy in proactively satisfying customers, resolving issues and exceeding expectations. Concierge brands win by maintaining a painstakingly complete understanding of unique customer needs and preferences.

- Points of differentiation: Benchmark levels of service, intimacy and guest experience

- Examples: Publix, Nordstrom

8. The Clairvoyant: The clairvoyant retailer is one that uses both technology and human intuition to actually predict needs, preferences and desires on the part of its customers and proactively present products on that basis. Unlike those that provide latent recommendations based on customer buying habits, clairvoyant retailers actually use their skill to present opportunities for discovery and surprise.

- Points of differentiation: Ability to leverage deep data insights to customise product recommendations

- Examples: Stitch Fix, Pop Sugar

9. The Engineer: Engineer retailers figure shit out. They use technology to solve product or service design problems that elude other brands, thereby creating solutions for consumers. These retailers excel at design thinking in all aspects of their go-to-market propositions, from what they sell to how they sell it.

- Points of differentiation: Differentiates on design and technological prowess

- Examples: Dyson, Away, Google

10. The Gatekeeper: Gatekeeper retailers are those that maintain position through regulatory or financial barriers to entry. They often dominate a market completely or as part of a small oligopoly. It’s important to note that while this ensures their existence in the short-term, it also makes them constantly vulnerable to attack from renegade retailers that may infiltrate their walled categories. The gatekeeper is both an enviable yet precarious market position for any incumbent.

- Points of differentiation: Differentiates on size, legislative barriers or market exclusivity

- Examples: Verizon, CVS, Luxottica

In the post-pandemic era, every retailer will need to determine which of these archetypes they are or can become and dedicate every resource to proving it each day.

Four Operational Dimensions

This model can be further understood by breaking it into four distinct operational quadrants. For some retailers, their primary source of dominance will lie in the content they are able to produce. This may take the form of media, events, shows and other means of entertainment and community building. For others, dominance may be found in the realm of customer experience, focusing on means of engaging the shopper both physically and emotionally across the shopping journey, incorporating sensory elements. Others still will lay claim to the mantle of expertise and knowledge in their category, investing in benchmark training, certifications and programs to get products into the hands of employees. And finally, some retailers will dominate through a laser focus on creating and selling aesthetically and functionally superior products.

No single position is necessarily more or less effective than another. But it is essential that a clear choice be made and that every element of the marketing and operational plan serve to bolster that position. Too many brands that we work with tend to look initially at these options and declare themselves “a bit of everything.” But there will be no free buffet in the post-pandemic landscape.

Survival will lie in becoming a fully evolved incarnation of a specific archetype and positioning one’s brand as far from the perilous middle of their market as possible. This is not to suggest that retailers cannot mix attributes from adjacent quadrants. The brand that excels at expertise can also differentiate in experience. The brand that dominates in content may also choose to differentiate on product. What retailers must not do is attempt to be a little bit of everything. When that happens, they run the risk of being pulled into the centre of the market and within striking distance of apex predators.

Covid-19 has set fire to the old-growth forest that was pre-pandemic retail. While devastating on a human and economic level, the effects of the pandemic will also clear out decades of rotting industry underbrush. Only the healthiest and genetically soundest species of retail business will remain. And perhaps, if there’s any silver lining at all, it’s that such a burn will offer fertile ground and ample sunlight for new and extraordinary retail concepts to be born out of the ashes.

Doug Stephens is the Founder of Retail Prophet and the author of three books on the future of retail, including the forthcoming ‘Resurrecting Retail: The Future of Business in a Post-Pandemic World.’

Related Articles:

How an Exodus from Cities Will Reshape Retail

Could the Pandemic Make Retail Better?

How Could Radical Transparency Impact Retail?

Which Retailers Have Been Hit Hardest by the Covid-19 Crash?