How To Make New Zealand Water Safe

Ideasroom

Who to call and what to do at a drowning incident, plus Jonathon Webber’s advice on lax and absurd water rules

As New Zealanders head in their droves to our beaches, lakes, rivers and other waterways to escape the confines of Covid-19 restrictions, rescue and emergency services are bracing themselves for expected spate of fatal and non-fatal drowning incidents that sadly peak at this time of the year.

Most, if not all of these deaths will be deemed preventable, providing no consolation at all to the family left behind to grieve. Data from a recently published study by the University of Auckland suggest that, in coastal locations, around 9 percent of these people will never be recovered and returned to their loved ones. Strengthening the Drowning Chain of Survival is the key to preventing these tragedies.

Despite constant media reports of New Zealand “having one of the highest drowning rates in the OECD”, a dated and inaccurate statistic, our per capita drowning rate is only slightly higher than countries like Australia and Canada. Encouragingly, our drowning rate fell by almost 25 percent from 2004 to 2015.

However, while the drowning toll is heading in the right direction, we must not lose sight of the fact that in 2019 more than 100 people lost their lives to drowning, 82 of which were preventable. Then there are those that survive a drowning incident, some of whom suffer long-term or permanent disability. Hospitalisations due to drowning have doubled since 2003, and to date, no explanation for this has been found.

In fatal coasting drowning incidents from 2008 to 2017, only 4 percent of missing persons were wearing a lifejacket, and most were associated with boating. While Maritime New Zealand, harbourmasters and the Maritime Police have taken proactive steps in recent years to encourage and in some cases enforce the wearing of lifejackets, regional variances to these regulations exist. In a country the size of New Zealand, this is absurd.

In Auckland, everyone on vessels under 6m has to wear a lifejacket unless the skipper says it is safe not to. In the Waikato, it must be worn at all times. So what exactly is it that makes Auckland waterways safer or conversely Waikato’s more dangerous? We don’t allow regional variance on the wearing of seatbelts, so the question needs to be asked why is there not a national standard that makes the wearing of lifejackets in small boats compulsory.

Similarly, registration of recreational vessels only applies to personal watercraft (PWC) like jet skis and skippers do not have to hold any formal qualifications. Responsible skippers will undertake a Coastguard boating education course, but a person can purchase a boat off Trade Me, and the next day they are out in the middle of a commercial shipping lane with no knowledge of the rules of the sea, let alone safety or communications equipment.

Compare this to Queensland where a licence is required to operate a boat with an engine greater than six horsepower (HP), and a separate licence is required for a PWC. All boats with a motor of greater than four HP must be registered. Operating a vessel with blood alcohol limit of greater than 0.05 (50 milligrams of alcohol in every 100 millilitres of blood), being under the influence of drugs or refusing to supply a breath specimen is an offence.

Interestingly, if a person is convicted of a drink-driving offence on the road, they can also have their marine licence suspended or cancelled. In New Zealand, harbourmasters and the police are powerless to test recreational skippers that they suspect are impaired by alcohol or drugs. These people can simply decline a test. For a boating nation, this laxity in maritime laws beggars belief.

Another area of concern is bystander rescuer, and the phenomenon of “aquatic-victim-instead-of-rescuer”. This is where the would-be rescuer gets into difficulty and sometimes drowns, and the person who was initially in trouble survives. The main reason for this is attempting rescue without some form of flotation. Flotation need not been in the form of a life-ring or other rescue device; empty two-litre soft drink bottles, rugby balls, chilly bin lids, bodyboards or surfboards will do just fine.

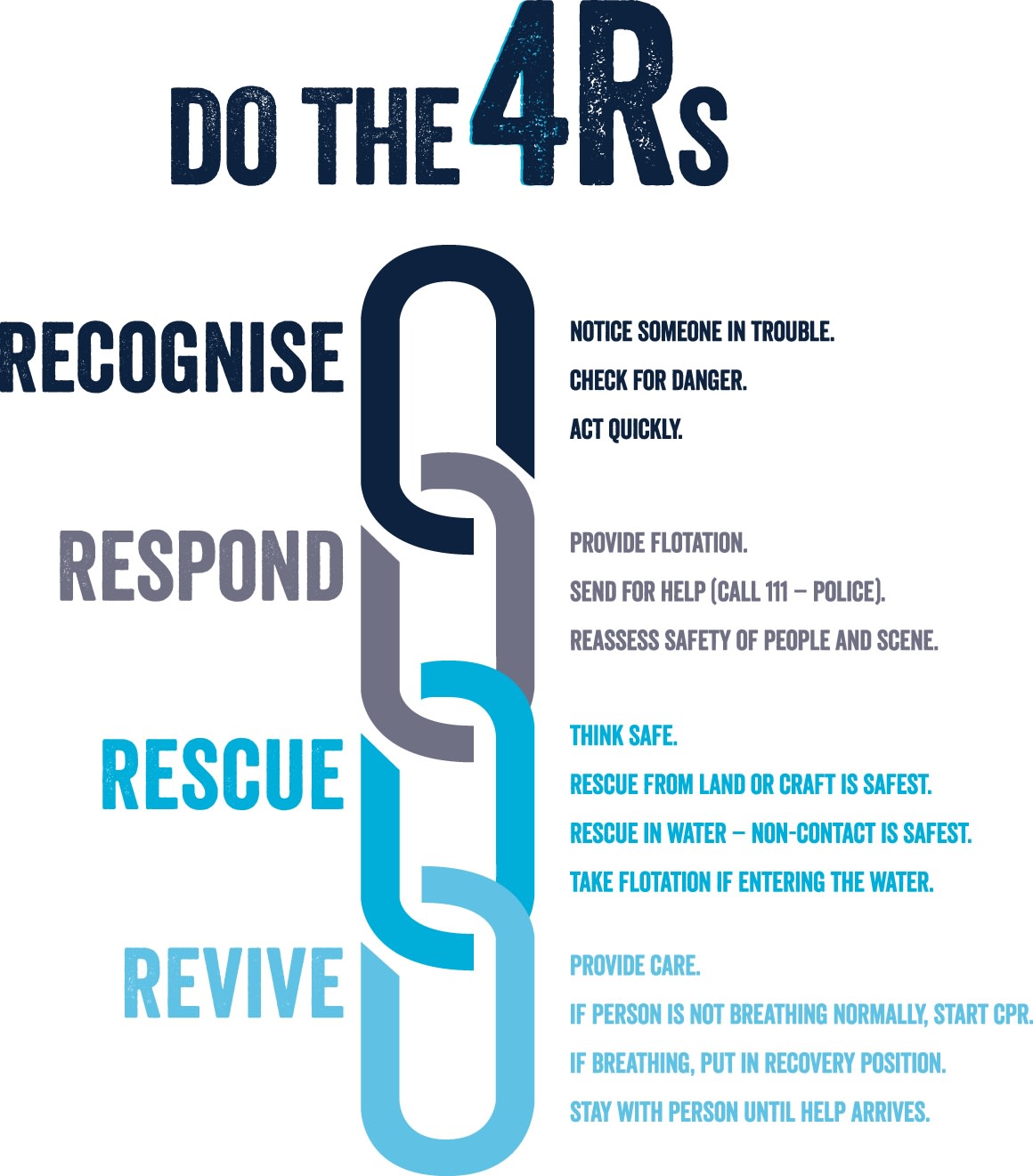

It is important to know that when you call 111, the agency that coordinates inshore water rescue is the police, so this is the service you need to ask for. Drowning Prevention Auckland has developed the 4Rs of aquatic rescue – Recognise, Respond, Rescue, Revive; a model that gives specific instructions of what to do if you see a person in trouble in the water and a handy resource to refer to in an emergency.

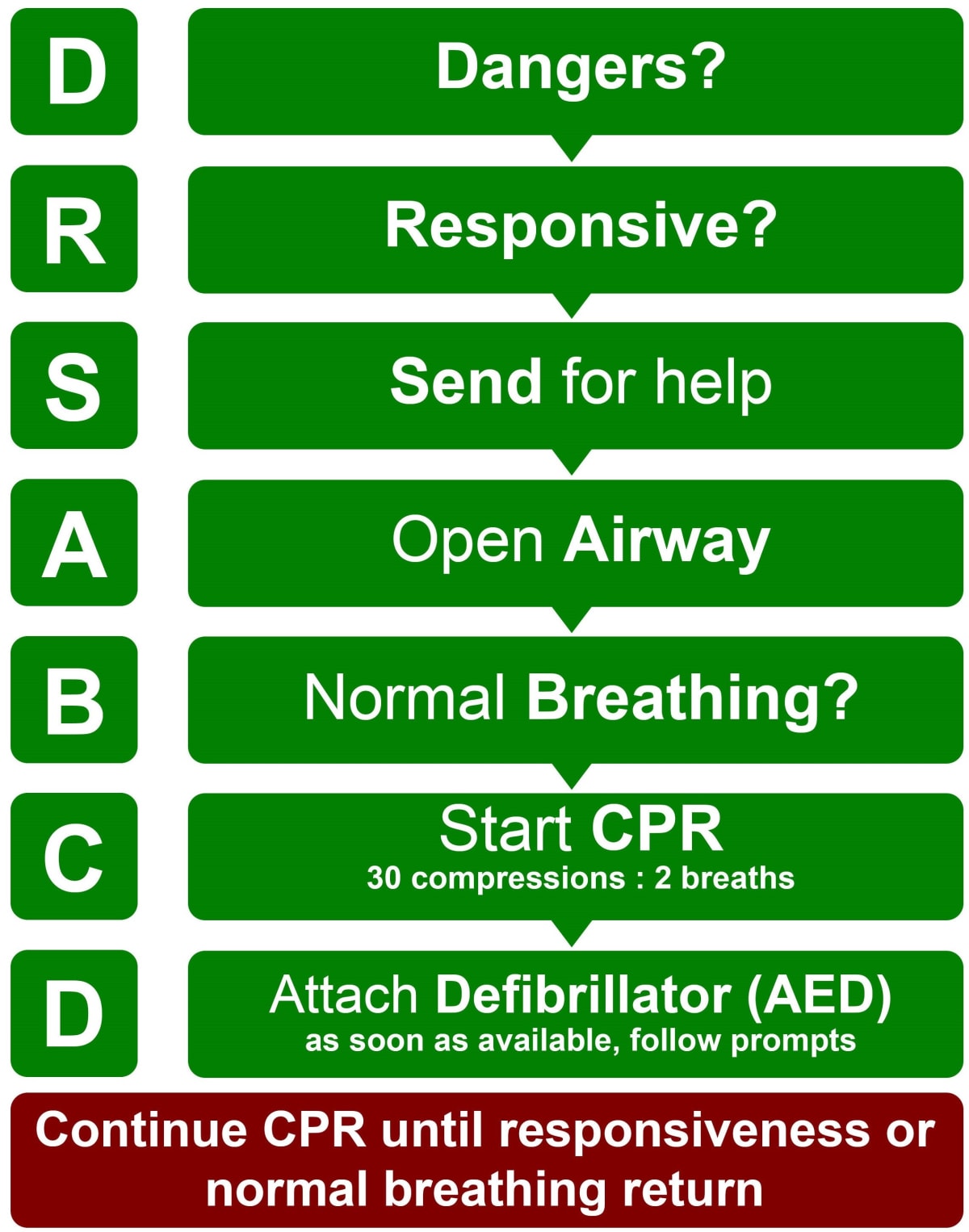

Knowing what to do at the scene of a drowning incident in terms of first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is also essential. Prompt initiation of CPR by a first aider is the single most critical intervention (other than safely getting the person out of the water) to improve their chance of survival. Rescue breaths (mouth-to-mouth) are more important than attaching a defibrillator in drowning. The defibrillator should still be attached nonetheless once CPR is underway.

It is worrying that in a country surrounded by water, some people still think rescue breaths are not necessary or “optional”. The New Zealand Resuscitation Council, which sets the standard for resuscitation and first aid in Aotearoa/New Zealand, has always recommended chest compressions and ventilations.

Of course, none of these measures would be necessary if New Zealanders took some simple steps to keep themselves and their families safe while in, on or around water. These include swimming at lifeguard-patrolled beaches, checking conditions and equipment beforehand, wearing a lifejacket, having emergency communications equipment or a locator beacon, learning swim and survival skills, knowing what to do if you see a person in trouble in the water and how to perform CPR.

As a nation, we must do better to prevent these incidents from occurring and recognise the life-long pain and suffering they cause from lives being cut short prematurely and unnecessarily at a time when we should all be enjoying New Zealand’s unique marine environment.

Dr Webber is a life member of the Piha Surf Life Saving Club and Surf Life Saving Northern Region, advisory board member of Drowning Prevention Auckland and executive member of the New Zealand Resuscitation Council