How Indigenous sign language is helping this woman connect with her culture

The word “deaf” isn’t just an adjective for Paula MacDonald — it’s part of her identity.

Growing up, she attended the Sir James Whitney School for the Deaf in Belleville, Ont., where she learned American Sign Language (ASL) as her primary means of communication.

It was there that “I really became culturally deaf,” MacDonald told CBC with the help of an ASL interpreter, explaining the sense of belonging she felt in the Deaf community.

It wasn’t until she attended a university for the deaf in Rochester, N.Y., that she found herself wanting to learn more about her other culture.

WATCH | What I want people to know about Indigenous sign languages:

MacDonald, who is half Cree and deaf, explains what learning Plains sign language means to her and why she wants to spread the word.

MacDonald was born in Saskatchewan and is half Cree from Treaty 4 on her mother’s side. She was adopted by a white couple in Ottawa at a young age.

Her parents were always supportive of her connecting with her roots, she said, but she was on her own to learn more about Deaf and Indigenous culture.

“I had gone to a couple of powwows, you know, kind of trying to learn more about the culture,” she recalls.

She said it was difficult because she needed sign language interpreters to understand what was happening.

Exploring intersecting identities

When she got to the National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID), MacDonald noticed a cultural diversity within the Deaf community she hadn’t seen before.

Meeting people from other countries who incorporated their country’s sign languages into conversation along with ASL made MacDonald curious about her own cultural background.

Through a bit of research, MacDonald found Marsha Ireland, a deaf elder from Oneida Nation of the Thames near London, Ont., who developed her own sign language to better connect with Oneida culture.

MacDonald invited Ireland to her college for a presentation. There, she learned not only about the Oneida sign language Ireland created for deaf members of her community, but also about other existing sign languages used historically by Indigenous groups.

That made MacDonald curious.

“It really got the ball rolling for me, realizing that I can’t just say, ‘Hey, I’m Indigenous,’ and that’s it,” MacDonald said. “I have to put in the work. I need to actually connect to my culture. So [Marsha Ireland] really lit the fire in me.”

Connecting to her culture

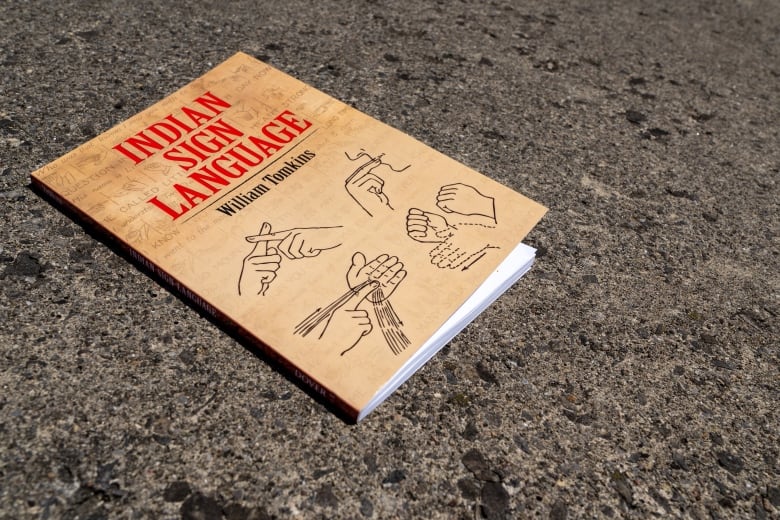

MacDonald is now taking Indigenous studies at Carleton University, and for the past three years she’s been teaching herself Plains Sign Language through online resources and dictionaries.

Plains Sign Language was traditionally used by people belonging to various groups, including the Cree, Blackfoot and Dakota. It spanned from the north Saskatchewan River, to northern Alberta, across Saskatchewan to Manitoba, and all the way down to the Rio Grande in Mexico.

It’s still sometimes used in western Canada today and in American states such as Montana, but MacDonald said it has been difficult to find resources to learn the language.

“The spoken languages are considered more sacred languages, so they’re a bit more protected,” she explained.

When it comes to sign language, MacDonald said “there’s a little less record-keeping [involved] and a little less storytelling to pass it on.”

While there are 70 spoken Indigenous languages in Canada, just three Indigenous sign languages are in use, according to Darin Flynn, professor of linguistics at the University of Calgary.

That includes Inuit Sign Language, Plateau Sign Language (used on the west coast by nations such as the Salish) and Plains Sign Language, which is the most widely known of the three today — with 100 fluent signers across the United States and Canada.

Flynn said Plains Sign Language wasn’t originally used solely by deaf individuals but rather as a “lingua franca” for people from different nations to communicate with each other.

With the arrival of Europeans, sign language gained even more importance. Then, much like English and French replaced many spoken Indigenous languages, Flynn said the development of ASL soon after the Europeans arrived meant it began to replace traditional Indigenous sign languages.

“People find it hard to put it this way, but it is kind of the colonial language. It’s the one that’s taking over,” he said. “[Deaf] people were taken to schools and taught sign languages that were precisely not Indigenous ones.”

The parallels between Indigenous education and deaf education aren’t lost on MacDonald.

“[In both residential schools and schools for the deaf] … our natural languages were banned [and] were taken from us. We weren’t allowed to use them,” she said.

For MacDonald, learning Plains Sign Language not only connects her with own identity, but also helps to bring more awareness to the loss of Indigenous sign languages in general. She also hopes this awareness will help revitalize the languages.

For now, MacDonald said she will continue her self-education, and she plans to attend a Plains Sign Language camp in Saskatchewan in the future.

“I’m really hoping that [the language] will grow. And I think if it does grow, it will help me feel even more connected to my community,” she said.

COVID has put a spotlight on communication challenges faced by people who are deaf and hard of hearing —particularly because of the impact of masks. CBC Ottawa reached out to those in this community to ask about their pandemic experiences and what they want people to know about their lives.

Click here to meet two deaf teenagers navigating the pandemic and a teacher who reads lips.

If you have a story you’d like to share about being deaf, send us an email.