How A Terrorist Is Radicalised

Terror in Chch

The Royal Commission report into the Christchurch terror attack suggests who might be susceptible to right-wing extremism. David Williams reports

How do you spot a terrorist? An explanation of the Christchurch gunman’s radicalisation in the just-released Royal Commission report is a valuable guide.

It’s no sob-story, nor an attempt to engender sympathy for the Australian shooter’s troubled upbringing. Rather, the report’s meticulous work takes research into the roots of extremism and compares what we know about the terrorist, including from the Commission’s prison interview with him.

“While there is no common socio-economic profile, a number of studies have shown those who are susceptible to right-wing extremism to be young men who are educated and with relatively stable socio-economic backgrounds, but with limited employment prospects,” the Royal Commission’s second section says.

“Childhood exposure to violence and trauma can, in some cases, create a propensity to hostility, violence and authoritarian views which can act as ‘emotional precursors’ to a later adoption of extremist attitudes.”

Jolting personal experiences, such as a traumatic event, losing a job, or personality clashes, can make a person “more receptive to extremist worldviews, or accelerate their radicalisation”.

The Royal Commission report paints a picture of the Christchurch terrorist as an introspective loner who was living, travelling and preparing for the attack from the proceeds of the estate of his father, who committed suicide, possibly with his son’s help. Bullied at school, and traumatised by his parents’ divorce, the Australian shooter expressed racist views from a young age – views that seemed to intensify the more he travelled.

“We see the terrorist attack as resulting very much from an unhappy conjunction of his personality (affected as it may have been by his upbringing), his financial circumstances resulting from the money his father gave him, his underlying political views (particularly his ethno-nationalist views and his belief in the Great Replacement theory) and his way of life (funded with his father’s money) which limited the likelihood of his views being tempered by ordinary interactions with others,” the report says.

The Christchurch terrorist’s early life in Grafton, New South Wales, in Australia, has the hallmarks of someone likely to be vulnerable to right-wing ideologies.

His parents separated when he was young, and the family home burnt down. After the separation, the terrorist became clingy and anxious, and he didn’t socialise well. His mother’s new partner hit the whole family – mother, son and daughter.

Video games, including role-playing games and first-person shooter games, were a major part of the terrorist’s life from six or seven. He had unsupervised access to the internet from a computer in his bedroom, and started using the 4chan message board at 14.

His racist views started at a young age. He was disciplined at school for anti-Semitism, and made derogatory comments about his mother’s partner’s Aboriginal ancestry. The high school’s anti-racism officer described him as “disengaged in class to the point of quiet arrogance, but also well-read and knowledgeable, particularly on certain topics such as the Second World War”.

Between the ages of 12 and 15 he was bullied because of his weight. He had few friends.

After his father was diagnosed with lung cancer, the terrorist started exercising compulsively and dieting, losing 52 kilograms. In 2010, his father committed suicide – his 19-year-old son “discovered” the body. The report notes his “not particularly convincing denial” about being involved in the suicide.

The illness and death of his father caused “much stress” and it’s thought he received “limited” counselling. The terrorist and his sister received about $A457,000 each after their father’s death, largely from a settlement claim arising from exposure to asbestos that caused his cancer.

All the while, he kept playing online games – including with a New Zealander in the Waikato who would end up becoming a referee for his gun licence – using the online chat to express his racist and far-right views.

Some lone-actor terrorists have personality disorders and mental health conditions – but, generally speaking, violent extremists are more likely to have personality “issues”, rather than disorders. This, the report says, can make them difficult to engage with and lead to social alienation.

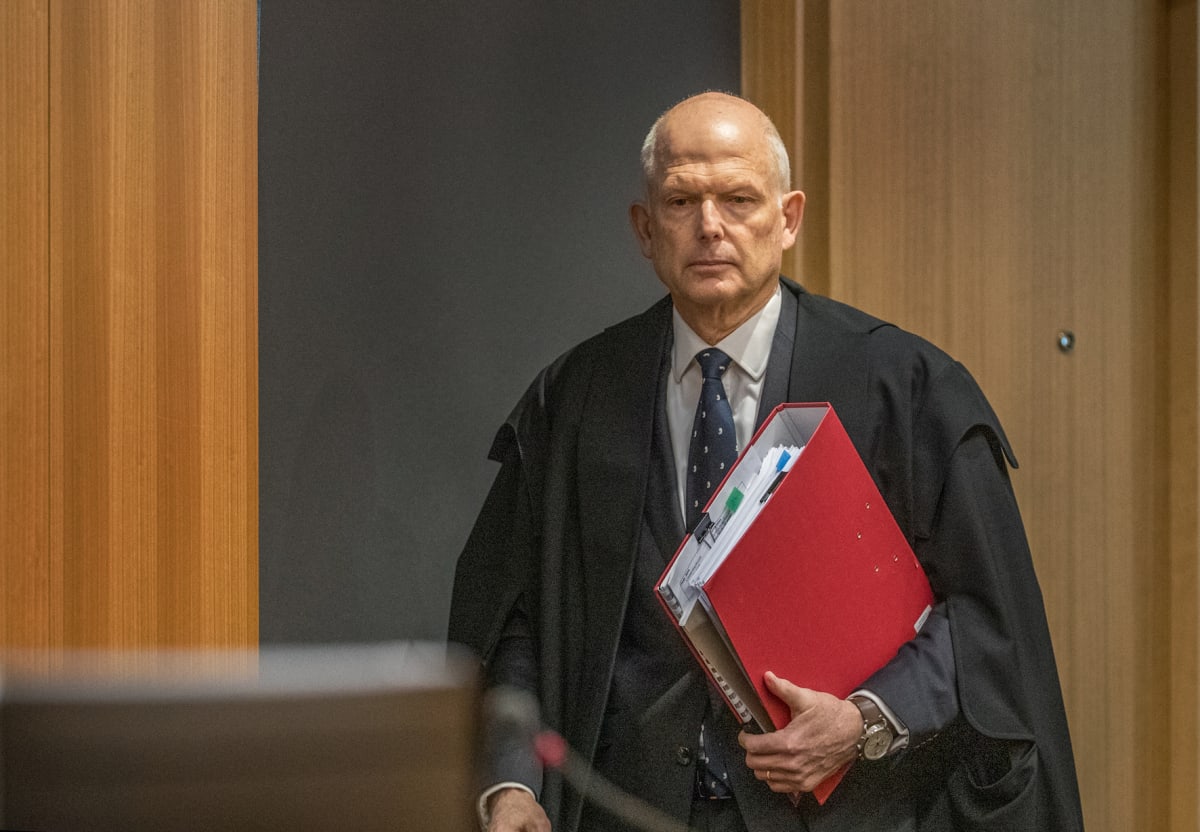

(In his sentencing notes, Justice Cameron Mander said of the Christchurch terrorist: “A clinical psychologist considered you displayed a range of traits akin to personality dysfunction but that they did not reach the level of severity to constitute a full-blown personality disorder or clinical syndrome.”)

In saying that, even terrorist loners indulge in groups which reinforce their extremist worldviews and solidify their thoughts of dehumanisation, crisis, and a belief that using violence is legitimate.

Understanding what causes individuals to radicalise to violence is crucial for public sector agencies, organisations, community groups and individuals, the report says. Weighing the significance of indicators, such as whether a right-wing extremist is willing to act on what they say online – “requires a sophisticated knowledge of the dynamics of right-wing extremism”.

That’s not just the domain of police and security agencies – the public has a role to play, too. As a result of the Royal Commission recommendations – all of which were accepted by the Government – a counter-terrorism campaign, akin to “If you see something, say something”, will be rolled out. Also, a new system will be created for reporting concerning behaviour and incidents.

The path to violence for extremists varies, generally, depending on their life experiences, social groups and wider socio-economic and political environment, the report says. It’s not linear, either – one person’s rate of radicalisation might be different to another.

Extremism is characterised by rigid and uncompromising beliefs “outside the norm of a society”, often with an “us versus them” mentality, favouring the supremacy, or strong loyalty to, a particular group. That group’s survival is contingent on hostility and suppressions of outsiders. Proponents are motivated by a desire change society to achieve their idealised vision.

Most people who subscribe to an extremist ideology don’t commit violence, the Commission’s report says. But even non-violent behaviour – such as protests and campaigns of vilification, which while abhorrent are often legal – can be harmful, and sow fear and division.

This “hateful extremism” (a term used by the United Kingdom Commission for Countering Extremism) uses dehumanising and divisive rhetoric to try and shift acceptable debate towards, for example, Islamophobic and anti-immigrant views.

The far-right covers a range of views, including pro-western nationalism, and the idea western civilisation and values are under threat from immigrants and ideas such as multiculturalism. But the sweep of the far-right also takes in conspiracy theorists (think QAnon) and anti-feminist ideologies.

The Christchurch terrorist’s thinking, the report says, “was far right in nature and showed many of the signs of ethno-nationalism”.

“He travelled widely because he could and had nothing better to do.” – Royal Commission report

In his interview with the commissioners, the terrorist says he started thinking politically at about 12. His main concerns were immigration “particularly by Muslim migrants into Western countries”. Yet, jarringly, while working as a personal trainer, he did community work at an Australian Aboriginal community.

When older, he told his sister he might be autistic or sociopathic because he didn’t care for people, including his own family, even though he knew he should.

(Justice Mander’s sentencing notes state: “As far as I am able to gauge, you are empty of any empathy for your victims. You remain detached and appear entirely self-centred. You have not displayed any discernible distress at your offending, which you recollected to the health assessors in an abstract and unemotive fashion. Stripped of your warped ideological and political trappings, you present as a deeply impaired person motivated by a base hatred for people who you perceive to be different from yourself.”)

He stopped working at his Australian gym in 2012 after becoming injured and used his father’s money to go travelling. “He travelled widely because he could and had nothing better to do.”

In Europe he visited the sites of major Christian-Islamic battles, but there was no evidence he met extremist groups or trained with them. He was mugged in Africa. But the commissioners suspect other factors were far more important in his radicalisation.

A notable change of right-wing extremism in recent years is its move from the streets to the internet. Gone are the street gangs and protest movements – in this country, neo-fascist and white power groups were visible until the 2000s.

“Today, extremism has substantially, although not completely, moved from physical meetings and street activism to the internet and social media,” the Royal Commission report says.

What that means for a “lone actor”, like the Christchurch terrorist, is they’re “never quite alone”. They can plug into online communities instrumental in spreading right-wing ideology, often using platforms like Facebook and Twitter, and unmoderated fringe corners such as Gab. Other platforms, like Reddit and 4chan, have been “hijacked”.

“The extreme right-wing has exploited the power of the internet through an array of online platforms and spaces, which is uses to connect with like-minded people and ultimately to recruit new members, some of whom have committed acts of violence and terrorism.”

YouTube, where far-right videos are common, comes in for special attention in the report, as users are sent down a rabbit hole of “ever more extreme material”. (YouTube has made changes to such criticisms.)

Radicalisation is a process in which individuals become committed to an extremist ideology. The next step, when violence is seen as a feasible way to address their grievances, is called “radicalisation to violence”.

Not a cause, but a setting

The terrorist’s mother told authorities the more he travelled the more racist he became.

By early 2017, before he moved to Dunedin, his views were so extreme she was worried about his mental health. “She remembered him talking about how the Western world was coming to an end because Muslim migrants were coming back into Europe and would out-breed Europeans.”

But the Royal Commission says travel was more a “setting” for his “mobilisation to violence”, rather than its cause. For that, we have to travel back to the internet.

“Of far more materiality was his immersion during this period in the literature, and probably online forums of the far right, and the social isolation of his solo travel.”

When he reached New Zealand, the terrorist already intended to commit an attack – so commissioners are sure he wasn’t radicalised on these shores.

The terrorist sent books and right-wing publications to family members, introducing his beliefs.

“The individual used the internet to buy far right books, ebooks, publications and accessories to send to his family, such as a ‘black sun’ patch and a Celtic knot necklace with symbols used by white supremacist groups.”

He told commissioners extreme right-wing sites didn’t draw him in. For him, YouTube was a “far more significant source of information and inspiration”.

The Royal Commission found the Christchurch terrorist’s personality was suited to his grisly task.

“He has limited and perhaps no empathy for those he has been able to ‘other’, most particularly Muslim migrants in Western countries. This mean the was able to contemplate with equanimity large-scale murder of people he had never met. He is reasonably intelligent and was thus able to undertake the necessary preparation and develop a complex but actionable plan for his terrorist attack.

“He has no apparent emotional need for close engagement with others, largely eliminating the likelihood of ‘leakage’, that is the disclosure of his intentions to others who might inform counter-terrorism agencies. He also was or became technically proficient across a range of skills. In terms of computers and the internet he is very much a digital native and he was well able to modify firearms he acquired to best suit his purposes.”

Alarmed, but no alarm raised

As March 15, 2019 approached, the terrorist’s family became alarmed at his behaviour – but not so concerned to contact authorities.

In late 2018, during a trip to Australia, he told his sister and her partner he wanted to move to Ukraine as it was cheaper, and Dunedin was “too multicultural”.

His mother, and her current partner, who is of Indian ethnicity, visited the terrorist from December 31, 2018 to January 3, 2019, taking in Dunedin, Milford Sound, Te Anau and Invercargill.

There were tense and awkward exchanges. One morning, the gunman left a café without ordering because it was run by “migrants”, telling his mother he wanted his money to go to white New Zealanders.

His mother returned to Australia “petrified” about her son’s mental health and racist views, and his isolated existence, in a small empty flat, with no friends. She pleaded for him to come home to Australia.

But it was too late. The terror plan was too advanced, his funds running out. There would be no trip to Ukraine. In truth, it was never planned. He never responded to his mother’s plea.

Instead, he committed cowardly mass murder, slaughtering unarmed and defenceless people, including a three-year-old, who were praying. He maimed, wounded and crippled many others. Essentially, it was an attack on New Zealand’s way of life, based on warped beliefs rooted in religious and ethnic hatred and hostility.

Everything possible must be done to shine a light on individuals who share such beliefs, to ensure such a horrific crime doesn’t happen again.