From the US to Afghanistan: Rediscovering the mother who left me | US & Canada

For the first time, I hung some photos of my mother in my home. I cannot take credit for the idea; my six-year-old son Oliver asked if we could.

At first, the thought of her narrow face and long black hair adorning my living room walls gave me pause. The woman I had spent so many years trying to purge entirely.

Now I had a son, and he earnestly wanted to know about his roots, particularly his grandma Sharon. It forced me to rediscover the woman who had committed that greatest of female crimes: abandoning her child.

Oliver and I piled into our tiny coup and drove to one of those big-box crafts stores. In a scattered mess on a shelf, we found frames of various shapes and sizes and in an array of plastic, metal and wood. Red. Blue. Black. A gaudy chartreuse frame, which was, of course, the one Oliver wanted.

A sign below screamed at us: “Buy One Get One 30% Off!” The deal was perfect. I scanned the mess that so overwhelmed my minimalist sensibilities and settled on two of the plainest rectangles in the lot.

I did not want to spend much money on this project since I was not sure how I would feel seeing Sharon’s face every day. My home is a refuge for a racing mind. It is filled with love and warmth and fun, but it did not include my past. I had worked too hard to get over that. And when I say “get over” what I mean is that I struggle with it almost every day.

Photos, newspaper clippings and obituaries

Still, these were beautiful black and white photos that would lend an artsy quality to the room, I reasoned. Plus, they showed Sharon in her best light: being a badass.

In one she is wearing a loose hijab, her long hair spilling out from underneath the cloth. She is sitting next to the powerful Afghan rebel commander Ahmad Shah Massoud. He was assassinated two days before the 9/11 attacks. An inscription on the back of the photograph dates it to March 1993 – one month before Sharon died.

The other image shows Sharon sitting at a long boardroom table surrounded by people, including Peter Tomsen, the Special Envoy to Afghanistan under US President George H W Bush. She is the only woman at the table, and the look on her face – brows furrowed and mouth pulled into a tight line – says she is not fooling around. While the men stare at their notebooks, Sharon is locked in a serious stare with the diplomat across the room.

I found these pictures years after they were taken. I was visiting my grandmother, who has since passed away, at her house in Colorado when she pulled out an old file she had stored in the closet of her bedroom. It was a flimsy, cheap plastic thing, held shut by a worn rubber band.

The casing bulged with mementoes marking my mother’s life as a war correspondent and bureau chief in Pakistan and her tragic death. It was an archive of newspaper clippings, obituaries, and remembrances from colleagues, mostly compiled by Sharon’s The Associated Press news agency colleagues after her death. It included the photos I was about to hang on the wall of my home.

Grandma had held onto the file for almost 25 years, fearing that I would throw it away or, perhaps, burn its contents. She had been right about that; it was good that she had waited.

The trove flew back with Oliver and me to our home in suburban Boston. We had looked through the file’s contents, but it was these two photos that had struck me. It is not every day that you see a photograph of the woman who was your mother sitting beside a rebel commander in Afghanistan.

She left me

Oliver watched as I put the photos into their frames.

“Let’s put them here, next to our pictures,” he said, pointing at a bare spot beside our family photos. I thought about it for a second, then hammered in the nail.

I hesitated because for much of my life I had hated my mother with real gusto. It was obvious anger that spewed from my mouth at every opportunity. It was not ordinary teenage angst. I hated her because she left me – for her career.

“Was she addicted to drugs?” people often asked after I disclosed that she had walked out on me. They would ask me this question or others like it – “Was she mentally ill?” was another favourite – steeped in empathy and confusion, a subtle attempt at finding some meaning in the mess. And because, really, the notion of a woman leaving her baby is almost inconceivable.

Years passed, and she stayed further and further away. I turned five, eight, 10, 12. And off to Dallas, New York, New Delhi, Islamabad she went. I turned 13. And she returned to Colorado in a coffin.

Gut-burning ambition

Sharon spent her evenings as a foreign correspondent mingling alongside heads of state, like former Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto, at fancy parties, or chasing freedom fighters through the dusty countryside of Afghanistan. Part of the foreign correspondent lifestyle is glamorous – hobnobbing, parties and politicians, beautiful old buildings in exotic locales, dalliances, spur-of-the-moment flights, information they are privy to while the rest of the world remains unaware. The sense of power intoxicates.

Long before she lived that lavish life, Sharon was a young woman in a big mess: an unintended pregnancy at 24 with a married man 20 years her senior. Unsure of what to do, she simply ignored the problem. A few months later, I showed up.

Sharon and I were misfits, never comfortable in our skin there; we dreamed of big cities like New York, London, Hong Kong and so we looked elsewhere to find our places in the world.

I spent the first few months of my life in foster care and was then sent to live with my mother’s parents in Lamar, the Dust Bowl outpost in Colorado where Sharon had grown up. She had always been desperate to leave Lamar, and she did so the second she could. She knew there were not many opportunities in town for people like her: the ones with gut-burning ambition.

Lamar is farming country. A rural town where Friday and Saturday night entertainment might consist of cruising Main Street after the high school football game. Life there was compact. You attended church every Sunday (Wednesday, too, for my grandparents). Adults worked their nine-to-five jobs at one of the three banks in town or as a checker at the local grocery store, like grandma. If there was a special event – a rodeo, a travelling carnival, a 4th of July parade – the entire town showed up. Sharon and I were misfits, never comfortable in our skin there; we dreamed of big cities like New York, London, Hong Kong and so we looked elsewhere to find our places in the world.

Fatherless

The palpable rage I experienced, though, was not only because my mother left me. She kept the circumstances surrounding my birth, including the identity of my father, a secret from everyone. Nobody knew who he was, not even grandma – or that is the narrative I was told. It took 38 years of digging for the truth, but I did not stop until I found it.

In our tiny town, my childhood was characterised by being known as the kid without a dad, the kid whose mum ran off. But having a strange family dynamic in Lamar was not uncommon. Two of my close friends lived with their grandparents. And plenty of kids in Lamar did not have dads. Their fathers worked in Wyoming and Northern Colorado on the oil rigs, and they returned home every few months. Grandma said they were deadbeats who left for women or drugs.

These kids, though, they at least knew why their fathers were gone. Meanwhile, I did not know a single thing about mine. I was not sure if he chose to leave or if my mother kept him a secret out of spite. I did not care about it so much when I was young, but as I grew up, the ghosts of my childhood haunted me.

When I was too young to understand the implications of parental abandonment, my “orphanhood” and mysterious origins were nothing more than a simple joke.

“Tracee doesn’t know who her dad is! Isn’t that funny?” my best friend, Heather, exclaimed to her mum one day. Heather and I danced, twirled, and laughed about this oddity until we collapsed on the hardwood floor. How could a little girl not know one detail about her father?

The unusual nature of my provenance was far from sad for two five-year-olds who loved My Little Pony and watching Bon Jovi on MTV when the adults were not looking.

As Heather and I frolicked at the kookiness of my family, the seriousness of which we could not truly grasp, her mum became awash in heartbreak. “Girls, this isn’t something to laugh at,” Heather’s mum said.

Forgiveness

In later years, forgiving my mother seemed an insurmountable feat, one aggravated by the fact that she was never around to apologise. I went from an unaware little girl to an adolescent so angry I drove to the cemetery one night with two friends and dumped cheap beer all over my dead mother’s grave.

I declared, to myself and anyone who would listen, that I would never give in, never forgive my mother, because doing so meant giving her a pass for her shameful actions.

The imperceptibility of anger brought something else in its place: a profound sadness I had never before let myself feel.

This belief went deep into my bone marrow until, one day, I noticed that I did not hate her guts. I still loathed her and the all-encompassing childhood trauma she inflicted on me, for all the scars I carried and still wear. But strangely enough and without fanfare, most of the red-hot anger and hatred was gone. Those once heat-emitting scars had cooled. I had fought my way through the fire. There was no one shouting that I had made it out the other side, scarred though I was but the worst was behind me.

The imperceptibility of anger brought something else in its place: a profound sadness I had never before let myself feel.

What I know is this: forgiveness did not happen overnight. The realisation of it, however, came suddenly and without warning. It was similar to having a thief steal something unimportant and not noticing for a few weeks. Nor did I seek out to grant her forgiveness. But giving my mother an elusive pardon was indeed a herculean achievement, though I could not see it at the time.

After I had Oliver, I started to soften. I started to view her with more empathetic eyes, as a human instead of the flawed parent who could never live up to the title of “Mother.” I noticed this initial softening one day when a close friend made a comment critical of Sharon. Instead of adding to the vitriol, as I usually did, I suddenly thought: “But wait, what about this?” It took a long time to discover who she might have been and better understand her decisions.

Sharon’s ghost

We hung these photos in 2018, and that happened to be the same year I turned 39 – the age Sharon was when she died. There is a strange emotional connection when you reach the age of your mum’s death.

Numbers have a way of making time seem coincidental, a reminder that nothing is permanent.

It is chilling to know Sharon will forever have her youthful appearance. Her skin will stay bright and taut, her hair full. By contrast, my 91-year-old grandmother’s face was filled with wrinkles. Her body sagged in the usual places. She looked 91.

I have already reached the point where I can compare myself to my mother physically. She has stayed the same age while I have grown older. What will I think when I look at my mother at 39 when I am 50 or 60 or 91? It is new territory from here on and, in a way, I will be living the life she never did.

On the day I turned 39 it was the 25th anniversary of her death.

Numbers have a way of making time seem coincidental, a reminder that nothing is permanent.

I have long forgotten the sound of Sharon’s soft-spoken voice, and I can no longer recall her image without looking at a photo. As time passes, I wait for any lingering remembrances of her to evaporate.

Her helicopter accident, among other childhood traumas, brought with them a heightened awareness of my own mortality and a preoccupation with death. It haunts my thoughts every day, and especially in situations where I am faced with what I see as a perceived threat to my life, which could be anything from travelling on an aeroplane to driving next to another vehicle on the highway. I convince myself my time has come. This is it. I am done. This is how it ends. It does not seem to take much to send me down this train of thought. I might be sitting across from a friend at a coffeehouse when a dark thought appears: “Which of us will be the first to go?” These thoughts come at inopportune times and without any forewarning. And they have been with me for as long as I can remember. I wonder at times if this is Sharon’s ghost.

The scars of childhood

The passing years have allowed me to see at least one benefit of ageing – namely, the ability to separate my worth from my childhood. I no longer identify with my flawed parents or what they did, how they acted, or that no one protected an innocent child. Their bankrupt decisions do not make who I am.

It is progress to have Sharon’s photo on the wall, in that I found a comfortable, yet realistic, place for her in my life. The scars of my childhood helped turn me into the person I am today, and for that I am grateful. I would be a different person today, of course, if I had had a different childhood. It helps to remind myself of this on the days I wish I had been adopted. I would be less afflicted in a general sense, but maybe I would be too comfortable, less driven to succeed. There is no way of knowing if things would have been better or not as good. Still, these thoughts permeate my thoughts on bad days and good days. As with any of life’s complicated matters, the two live side by side.

Going back to the day Oliver and I hung these two photos: It was right around April, the same month she died, only 25 years later. Her image on my living room wall turned out to be something I enjoyed. I looked at my son. Where did he get his blond hair? Ice-blue eyes? Not from Sharon. This was apparent.

“It feels kind of nice,” I said to myself.

Those two photos are still hanging in the same spot we originally placed them. They have become part of the background noise of our lives, not a provocation or reminder of all I missed out on as a child, as I had once feared they might be.

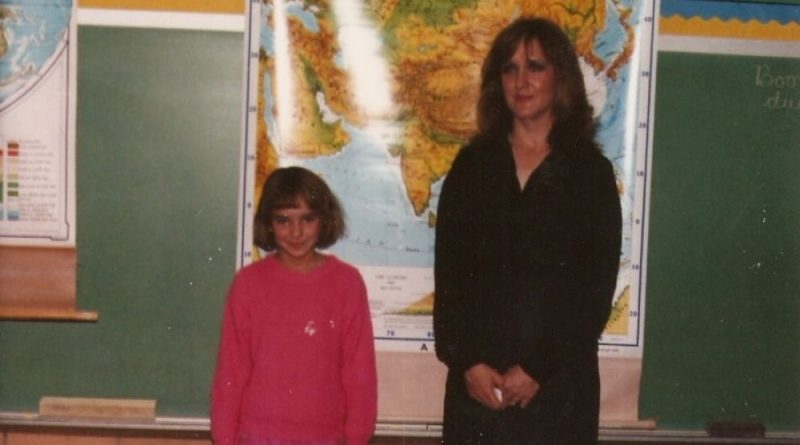

![Sharon [Photo courtesy of Tracee Herbaugh] Rediscovering the mother who left me - Tracee Herbaugh - DO NOT USE](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2020/1/15/0fae7d743f72407c910e729d0fe71931_7.jpg)

![Sharon Herbaugh [Photo courtesy of Tracee Herbaugh] Rediscovering the mother who left me - Tracee Herbaugh - DO NOT USE](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2020/1/15/42878570867845de908c41360c69a599_18.jpg)

![Sharon astronaut [Photo courtesy of Tracee Herbaugh] Rediscovering the mother who left me - Tracee Herbaugh - DO NOT USE](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2020/1/15/9a06301b3ce14b9d993c2830f0b13437_7.jpg)

![Herbaugh family [Photo courtesy of Tracee Herbaugh] Rediscovering the mother who left me - Tracee Herbaugh - DO NOT USE](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2020/1/15/a454c8bb0c2b440eb2f0991b05ffa379_18.jpg)

![The writer and her kids [Photo courtesy of Tracee Herbaugh] Rediscovering the mother who left me - Tracee Herbaugh - DO NOT USE](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2020/1/15/43e7e35ca9474008b985448dbb46b825_18.jpg)