Energy crunch: Russia could reap windfalls as other nations reel | Fossil Fuels News

Bangalore, India – Raymond D’Costa woke up soaked in sweat. It was midnight and the power was out in his neighbourhood in Bangalore, India’s third-largest city. When it returned, the voltage was so low that the ceiling fan barely moved. A fresh outage took away even that whiff of comfort.

This pattern played out repeatedly on a recent sultry night. But D’Costa, a 43-year-old executive at an education startup, is worried that the worst is yet to come. “It’s going to get really bad,” he told Al Jazeera.

A desperate coal shortage at India’s power utilities this month is stoking those fears, as supplies struggle to keep up with a burgeoning demand for electricity in a reviving economy.

Several Indian states enforced power outages in October that at times lasted up to 14 hours a day. Yet India’s challenge is hardly unique. Multiple Chinese provinces have suffered blackouts in recent weeks as coal supplies there fall short of demand. Europe is also grappling with rising electricity costs as supplies of natural gas fail to meet the needs of economies that are finally on the move after 20 months of the coronavirus pandemic.

But while there are plenty of losers, the global energy crunch is also minting winners – including Russia.

For years, President Vladimir Putin’s government has been criticised for Moscow’s refusal to move swiftly towards clean energy. Now it’s reaping the benefits of that decision, with energy-hungry Europe, China and India looking to Russian gas and coal to play saviour.

Consider the irony: As global leaders gather in Glasgow for the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) on Sunday to recommit to fighting climate change, Moscow’s emphasis on fossil fuels is what could keep homes in many of the world’s largest economies warm this winter.

“All of this gives Russia real leverage,” Thierry Bros, an energy industry analyst and professor at the Sciences Po research university in Paris, told Al Jazeera.

A perfect storm drives windfalls

Russia is poised to benefit both financially and strategically. It’s home to some of the world’s largest reserves of gas and coal, and fossil fuels make up the lion’s share of its export revenue.

With the global economy recovering at a historic rate and the demand for energy shooting up, benchmark prices for natural gas hit all-time highs in Asia and Europe in October. Coal prices are four times what they were a year ago.

As global leaders gather in Glasgow for the COP26 summit on Sunday to recommit to fighting climate change, Moscow’s emphasis on fossil fuels is what could keep homes in many of the world’s largest economies warm this winter [File: Yves Herman/Reuters]

As global leaders gather in Glasgow for the COP26 summit on Sunday to recommit to fighting climate change, Moscow’s emphasis on fossil fuels is what could keep homes in many of the world’s largest economies warm this winter [File: Yves Herman/Reuters]“It’s a perfect storm,” said Alexander Gabuev, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center.

China, already a major market for Russian coal, is looking to increase imports amid its shortages. And Russian energy giant Gazprom is expected to supply 10 billion cubic metres of natural gas to China this year via the China-Russia east route pipeline, according to China nationalist tabloid the Global Times. That is double last year’s volume.

Under a deal signed this month, Russia committed to sending up to 40 million tonnes of coking coal to India every year.

And Europe is pleading with Russia for additional gas from Gazprom beyond what the state-run firm is contractually obliged to supply. It is also seeking Russian coal.

“The sky-high prices are promising to give Russia windfall revenues,” said Bros, adding that back-of-the-envelope calculations show Gazprom could earn $10bn in additional income this year.

With Europe, there’s a larger game afoot too, said Gabuev.

“Gazprom wants to use the current scenario to get Europe to issue regulatory approvals for Nord Stream 2,” he told Al Jazeera, referring to the controversial gas pipeline built to bypass Ukraine and deliver Russian gas to Europe across the Baltic Sea. The United States, Ukraine and some former Soviet-bloc nations fear Nord Stream 2 could make Europe even more dependent on Russian energy.

The green energy transition

While some analysts have suggested that a lack of investment in fossil fuels has contributed to the current energy crunch, the coal shortage in India and China stems from a sudden resurgence in global energy demand, not from the global march towards a greener energy mix, say observers.

“I would argue that if countries had embraced green sources more aggressively a decade ago, we wouldn’t be in this situation,” Steve Herz, international climate policy adviser at the US-based environmental group Sierra Club, told Al Jazeera.

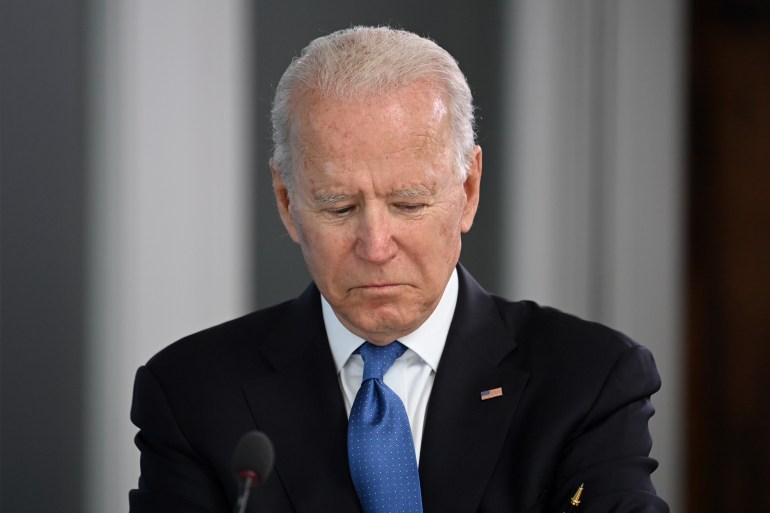

The White House called in August for OPEC to pump more oil to control prices, even though greening up the United States energy mix is central to President Joe Biden’s economic revival plans [Photo by Leon Neal – WPA Pool/Getty Images]

The White House called in August for OPEC to pump more oil to control prices, even though greening up the United States energy mix is central to President Joe Biden’s economic revival plans [Photo by Leon Neal – WPA Pool/Getty Images]Even the Kremlin is slowly changing its approach towards climate change. Earlier this month, Putin announced that Russia would attempt to turn carbon neutral by 2060. It wasn’t a firm commitment of the kind that the US, Japan, China and many European nations have made. But it represents a shift from “two-three years ago, when Russian leaders appeared in denial about climate change,” said Gabuev.

Still, the ongoing energy crisis risks undermining the credibility of Europe’s ambitious plans to rapidly move towards green power sources, said Bros. It doesn’t help that the continent’s current plight stems in part from less-than-expected wind in September, which led to a failure to produce enough renewable energy.

“Russia wants to show that Europe’s Green Deal is poorly thought out,” Bros said. “This helps its case.”

The scramble to purchase Russian gas and coal also underscores how much longer major economies are likely to remain dependent on fossil fuels. Coal feeds roughly 70 percent of India’s electricity needs, and over 60 percent of China’s, according to the International Energy Agency.

Bros also pointed to the White House’s call in August for the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to pump more oil to control prices, even though greening up the US energy mix is central to President Joe Biden’s economic revival plans. Amid its coal shortages, China is also loosening regulations to enable faster production.

According to Herz, this hunger for more fossil fuel supplies is a response to a short-term challenge that shouldn’t be confused with the “long-term imperative” to dump nonrenewable energy sources. He warns that it would be “extremely counterproductive” for countries to double down on fossil fuels as a result of this crisis.

But getting to that “long-term” could be fraught with financial and geopolitical complexities. Gabuev said he doesn’t see how Europe has a real alternative to natural gas from Russia for the next 10 to 15 years.

Until then, Bros fears many more crises like the current one, spawned by a gulf between a demand for cheap fossil fuels and a policy focus on clean energy sources. “I think you’ll continue to phone me very often,” he said.