Chasing The Holy Grail of Circular Fashion

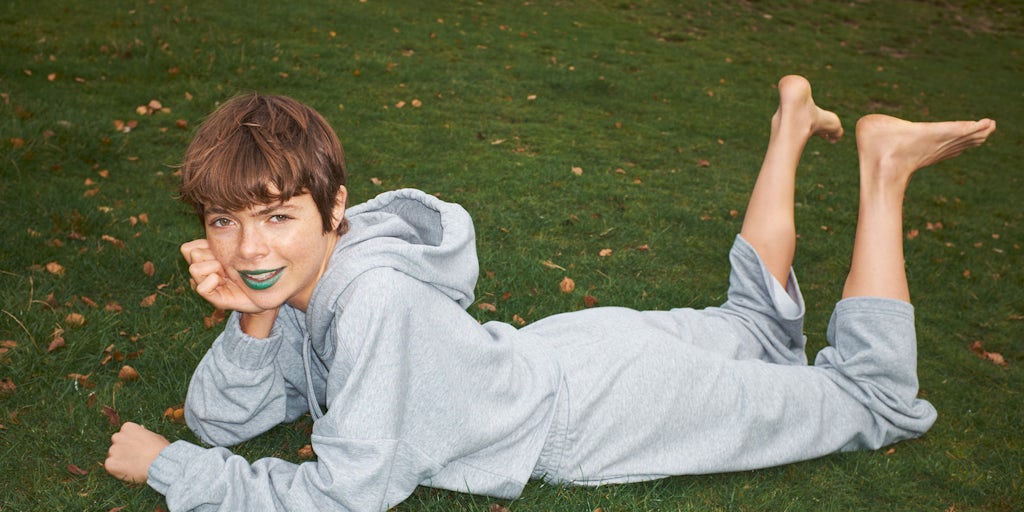

LONDON, United Kingdom — Monki’s newest drop is made from old clothes.

The H&M-owned brand’s capsule collection of grey sweatsuits is the latest recycling experiment by a global fashion brand. So far, so 2020. But the Swedish fast-fashion giant has bigger ambitions for this particular project.

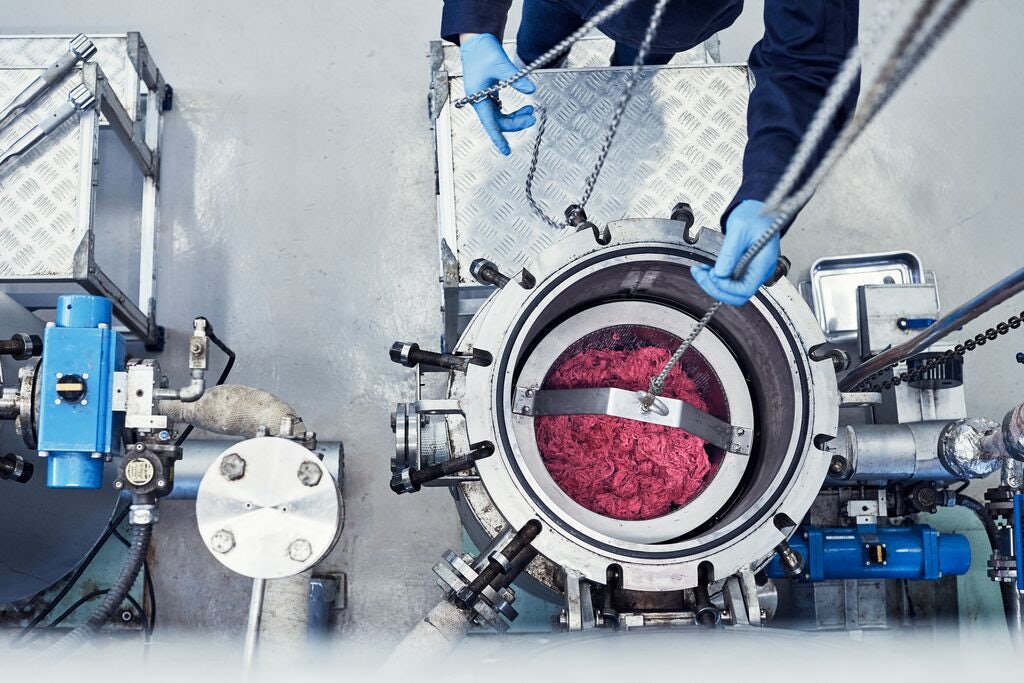

For the last four years, the H&M foundation has been working with the Hong Kong Research Institute of Textiles and Apparel (HKRITA) to develop a machine that can take old stretch jeans, jumpers and sweatpants and, using heat, water and biodegradable “green” chemicals, turn them back into materials that can be processed and re-spun into new clothes. Monki, a youth-focused brand that sits alongside labels like COS and Arket in H&M group’s portfolio, will be the first H&M brand to test-drive the new technology.

The ability to recycle old clothes back into new, high quality materials on an industrial scale is a top priority for the circular fashion movement, whose proponents envision an apparel industry designed to minimise waste and pollution. They have a long way to go: the Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates nearly 40 million tons of textile waste is sent to landfills or incinerated each year.

Much of that material would be impossible to upcycle into new clothes today. Long-standing mechanical recycling techniques — which shred materials like wool, cotton or cashmere to recapture original fibres — often do so at the expense of quality. Blended fabrics, which combine natural fibres like cotton or wool with synthetics like polyester, are particularly tricky to repurpose. And where the knowhow to turn old clothes into new material does exist, it has so far largely been confined to the lab or the odd pilot project.

But a flurry of high-profile new projects could move the needle in a material way.

Toward a Tipping Point

Over the coming months, one of Monki’s biggest suppliers is installing HKRITA’s machine. By early next year, it will have the capacity to transform around 1.5 tons of old textile waste daily into raw materials, replicating the technology at industrial scale for the first time.

The goal is to prove by the end of 2021 that the machine is commercially viable, paving the way to increase capacity.

HKRITA’s machine uses heat, water and biodegradable “green” chemicals to recycle blended textiles. Source: H&M Foundation.

“We have built a system … that gets us into the large scale now we can make a difference category,” said Edwin Keh, chief executive of the Institute.

To be sure, at current volumes, the machine will barely register in Monki’s overall product selection. Its first drop will be just a few hundred items sold online. But the 14-year-old brand, which markets primarily to young women, sees supporting initiatives like this as an important part of maintaining its relevance.

“The whole ‘Greta wave’ is our girl,” said sustainability director Jenny Fagerlin, referring to Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. “We want to be a frontrunner.”

Elsewhere, Kering, PVH and Target have formed a consortium with innovation hub Fashion for Good, Laudes Foundation and manufacturer Birla Cellulose to road test five chemical recycling technologies. And earlier this year, Ralph Lauren took a minority stake in material science startup Natural Fiber Welding, which is working to improve the quality of recycled cotton. The US luxury fashion brand said the investment is intended to “help create and scale a new industry standard for natural fibre recycling.”

We want to be a frontrunner.

Sweden-based Renewcell is already producing 4,500 tons a year of trademarked Circulose pulp, which is recycled from discarded textiles made from cotton and other natural fibres. It’s a raw material that can be re-spun into virgin-quality viscose or lyocell. So far, Renewcell has partnered with brands including Levi’s, H&M and Bestseller and it’s part of Fashion for Good’s new project.

It’s building a second 60,000 ton plant in Sweden scheduled to start production in 2022 and is expecting to expand its overall capacity to 360,000 tons by the end of the decade. Earlier this month, the company announced plans to list on the public market in Sweden.

The real transition from lab experiment to industrial scale is only just beginning. Renewcell’s volume represents an infinitesimal fraction of global textile production and it’s currently among the most mature products on the market.

The swift acceleration in efforts to bring textile-to-textile recycling technologies to market reflects evolving cultural and consumer trends, as well as the growing maturity of the innovations. Where historically brands have had to pay a premium for materials that didn’t perform as well or feel as good as virgin fibres, there’s growing confidence in the potential of the current crop of innovations.

HKRITA maintains the technology Monki is experimenting with can produce material that consumers would never know was recycled, at the same cost as mainstream fibres.

“Next year, we want to refine it; if we can get this to be cheaper than virgin, then it’s a really cool, compelling case,” said Keh.

The whole Covid thing has just made the circularity space hit overdrive.

The coronavirus crisis has also ratcheted up the fashion industry’s already-growing interest in sustainability. Conversations around green economic recovery plans have increased scrutiny on the sector’s climate impact, while efforts to improve fashion’s environmental performance have been among only a handful of topics that continued to resonate with consumers through the pandemic.

“The whole Covid thing has just made the circularity space hit overdrive,” said Cyndi Rhoades, founder of Worn Again, which has plans to build a demonstration plant for its blended textile recycling technology in the UK in the next few years. “It feels like we were working in a vacuum for so many years and you could only hear the sound of tumbleweed, and now it’s reached fever pitch and we’re working towards solutions.”

A Closed Loop System

There’s no guarantee any of the current crop of recycling projects will perform well enough to win further investment.

“We’ve been part of a couple of initiatives that have tried and died,” said Fagerlin. “It’s just sci-fi and it never really hits the market.”

Even if the technology succeeds in producing raw materials that can produce cheap, high-quality recycled fabric, working it into a complex global supply chain is a separate challenge that some experts predict will take decades.

Assuming its current series of test projects is successful, Fashion for Good estimates it will take between five and seven years to scale to fully operating plants. For that to happen, brands need to make commitments to the new materials that would incentivise manufacturers and investors to get on board.

HKRITA’s recycling technology produces polyester fibres and cellulose powder. Source: H&M Foundation.

“The capital gap is enormous,” said Kathleen Rademan, innovation platform director at Fashion for Good. A January report the organisation put together with Boston Consulting Group pointed to $20 to $30 billion in annual investment required over the next 10 years to develop and scale solutions like recycling technology that can help solve the industry’s environmental challenges.

And beyond the recycling technology itself, a whole new infrastructure is required to support a system that no longer treats old clothes as waste, but as feedstock. Many of the technologies currently under development can only handle specific types of material, which means more sophisticated sorting and supply chains need to be established.

“The world is still in the [research and development] phase of circularity as a system,” said Rhoades.

Nonetheless, these technologies have the potential to be game-changing. The new “green machine” Monki is using for this month’s capsule collection can process blended cotton and polyester, solving for one of the major infrastructure challenges. And it’s a modular system that can plug into existing manufacturing relatively swiftly. If all goes well this year, it’s a technology that will have the support of the H&M group to scale further.

“This supplier is one of the biggest in the supply chain; for them, there is no business case if it couldn’t be scaled up and replace all polyester in the future,” said Fagerlin. “I really hope in the next year we can build a roadmap that clearly says when.”

Related Articles:

Can Recycling Fix Fashion’s Landfill Problem?

Luxury Brands Burn Unsold Goods. What Should They Do Instead?

Fashion’s Growth-Focused Business Model is Not Sustainable. What’s the Solution?